A Hundred Thousand Orphans

My Experience with the Children of the Eritrean War

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

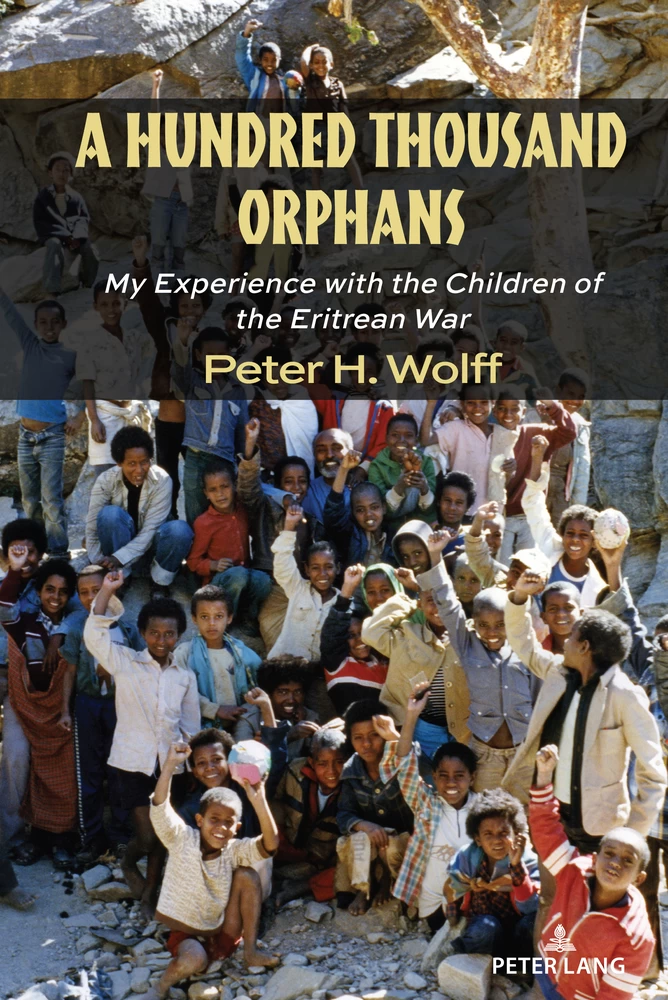

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Eritrea at War

- Chapter 1. The Road to the Base Camps

- Chapter 2. A Brief Overview of Modern Eritrea

- Chapter 3. The Base Camps

- Chapter 4. The Human Factor

- Chapter 5. Departures

- Chapter 6. Solomuna

- Chapter 7. Solomuna Revisited

- Chapter 8. Centers for Mothers and Infants

- Chapter 9. The Zero School

- Chapter 10. Cassandra’s List

- Chapter 11. Peace at Last

- Part II. One Hundred Thousand Orphans

- Chapter 12. Meeting the Challenge

- Chapter 13. Orphanages

- Chapter 14. Reunification

- Chapter 15. Group Homes

- Chapter 16. Education after Liberation

- Chapter 17. Community Child-Care Centers

- Part III. A Dubious Liberation

- Chapter 18. A New Government

- Chapter 19. Another War

- Chapter 20. The Peacetime Economy and Its Ramifications

- Part IV. The Legacy of the Zero School

- Chapter 21. The Orphans Revisited

- Chapter 22. Looking Forward

- Bibliography

- Additional Resources

- Biographical Data

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Children in the Asmara orphanage taking a break from activities.

Figure 2. Teacher playing with the children in the orphanage playground.

Figure 3. Two of the combatants working in the underground electronics workshop.

Figure 5. Caregiver with children at breakfast. (Asmara Orphanage)

Figure 6. Lunchtime in the group home.

Figure 8. Students in class at the Zero School.

Figure 9. The group home mascot.

Figure 10. Friends posing for the camera. (Asmara Orphanage)

Figure 12. The house mother and Tarik after he returned to his group home.

←xi | xii→Figure 14. Children heading off for their bath.

Figure 15. Students attending class in the Zero School.

Figure 16. Movie night under the stars.

Figure 18. Producing pharmaceuticals in the underground pharmacy.

PREFACE

In its 2005 annual report on The State of the World’s Children, the United Nations Children’s Fund estimated that armed conflict, drought, famine, and other unnatural disasters have deprived more than 60 million children of their families, their homes, and, ultimately, their identity.1 What happens to these children? What steps can be taken while they are still children that will give them a fair chance for a livable life? And what can their stories teach us about the effects of early experience on childhood development? These are global questions that have no global answers. Yet they must be asked and, whenever possible, be addressed at a local level.

Conventional wisdom holds that abuse, human cruelty, or trauma of some sort early in life will have serious negative outcomes. It may be, however, that the ability of children to rebound from the effects of early traumatic experience has much to do with the cause of that trauma: that is, whether it was due to maltreatment by other human beings (physical abuse, sexual abuse, deliberate injury of any sort) or to the consequences of man’s inhumanity to man (war, starvation, extreme poverty, etc.). This book tells the story of Eritrean orphans who spent their most vulnerable years of childhood under tremendous adversity but grew up to become self-reliant, productive adults with the courage to resist the authority of those who threatened their basic human ←xiii | xiv→rights and universal democratic freedoms. From their story, one can conclude that when the social (and ideological) conditions are right, vulnerable children can grow up to become remarkably healthy and ethically sound adults.

Eritrea is a small, poor country on the volatile Horn of Africa, a country whose people fought a thirty-year war for freedom and independence from Ethiopia. During that time, it educated a whole generation of children and laid the foundations for an open, democratic society. To get some idea of the conditions that made Eritrea’s foray into social democracy possible, I visited the base camps of the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) in 1985. What I discovered there was so extraordinary that I returned again and again thereafter.

I quickly learned that, if I wanted to understand what had made Eritrea’s social revolution even possible, I would have to learn many things about the country’s history, its cultural traditions, its child-rearing practices, its values, and its peculiar brand of Marxism. However, much of what I wanted to learn about its children I would probably not find in newspaper articles, pamphlets, or any of the excellent books that have been written about modern Eritrea. Instead, I would have to learn for myself by observing the children in their natural environment both in times of war and of peace and, wherever appropriate, by interacting with them and their caregivers.

Accordingly, after a brief description of the country’s geography, people, culture, and struggle for independence, Part I of this book establishes the wartime landscape and traumatic context in which the thousands of orphans and other lost children of Eritrea found themselves. Here I set the stage by recounting my early experiences visiting the base camps and medical facilities; interacting with the combatants, the doctors, and the children; and learning about the values by which they all lived. Within that framework, I also describe how the human factor—the courage, personal commitment, and self-discipline of the combatants—made this extraordinary experiment in nation building possible; how the EPLF rehabilitated and educated all the children in their care; and how, as part of this effort, the combatants integrated the best practices of the traditional village community with the goal of universal literacy and the progressive values of their social revolution.

Part II reviews the various programs and institutions that the postwar government used to reintegrate its hundred thousand orphans into their communities. From my personal experiences visiting the orphanages, reunified families, and small group homes, I was able to see firsthand how the children ←xiv | xv→who had survived the trauma of war were, under the aegis of the EPLF, continuing to mature and flourish.

Part III looks at what happened to Eritrea’s revolution once the external enemy had been defeated, only to be replaced by an internal dictatorship, and the values that had fueled the thirty-year struggle for independence were deemed no longer essential for the country’s survival as a sovereign state.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 192

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433199820

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433199837

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433199844

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781636670126

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20376

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (May)

- Keywords

- orphan Eritrea war victims orphanage group home childhood development child welfare EPLF Peter H. Wolff A Hundred Thousand Orphans My Experience with the Children of the Eritrean War

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Lausanne, Oxford, 2023. XXII, 214 pp., 18. b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG