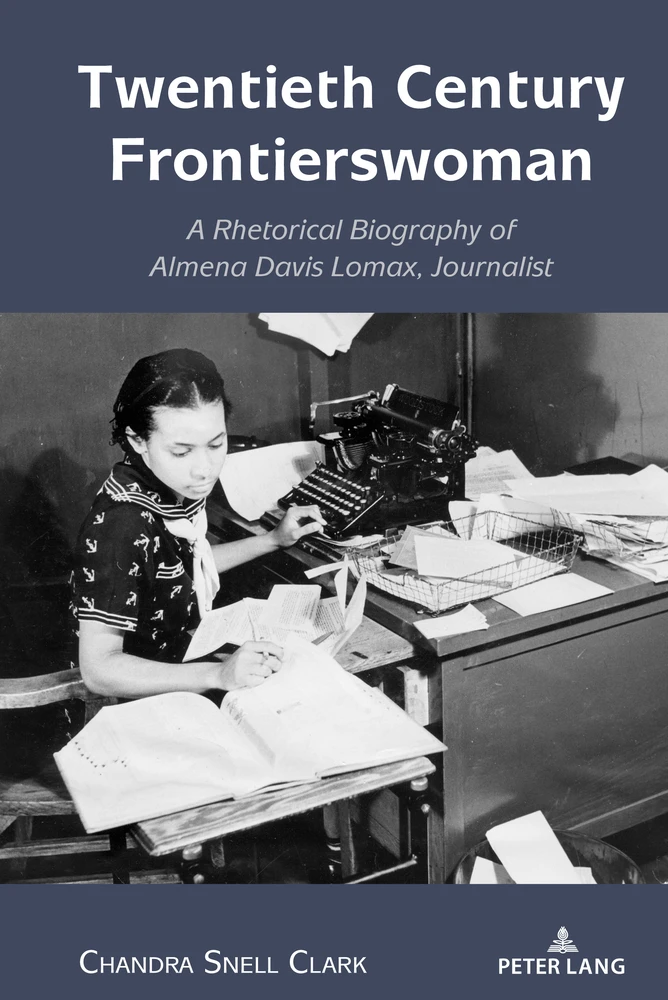

Twentieth Century Frontierswoman

A Rhetorical Biography of Almena Davis Lomax, Journalist

Summary

While African American women journalists' contributions to the United States' long civil rights struggle via their writings and speeches—particularly those of the late nineteenth, early twentieth century and late twentieth century—have received greater attention in recent years, there is yet much to glean from the Black women journalists who built upon the path set by journalist-activist foremothers such as Mara W. Stewart, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Anna Julia Cooper and others—African American women journalists of the mid-twentieth century. This project contributes to the larger discourse on race, rhetoric and media by recovering the work of a little-known African American newspaper publisher and journalist of this era, thus adding to the body of knowledge concerning an often-overlooked group for not only journalism, media, communication, history, African American studies and women’s studies scholars, but also for any reader with an interest in these areas.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Autorenangaben

- Über das Buch

- Zitierfähigkeit des eBooks

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Preface: “Passionate Attachments” as Creative Motivation

- Introduction

- A Rich Context: The Black Press, Black Women Journalists, Black Californians, and Black Los Angelenos

- African American Women’s Rhetorical Theory/Afrafeminist Ideology as Lens

- Rhetorical Biography

- Establishing a Journalistic Voice: 1940s–1950s

- Personal Nadir: 1958

- Expanded Focus, Familiar Means: 1959–1960

- Not Easily Categorized

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Davis Houck, Fannie Lou Hamer Professor of Rhetorical Studies (Florida State University) for support and guidance throughout this project; the Florida A&M University Coleman Library; the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Almena Lomax and Michael Lomax papers, Emory University; the Florida Education Fund for awarding the Junior Faculty Fellowship, which granted me a sabbatical in the fall of 2012 to work on this project; Dr. Valencia Matthews, Florida A&M University, for paid leave time; Dr. Yakini Kemp (retired, Florida A&M University) for class release time; the American Journalism Historians Association Maureen Beasley Award for Outstanding Paper on Women’s History Honorable Mention, Fall 2012; Madeline Thea Griffin, doctoral student in history, for research assistance (Georgia State University); Dr. Michael Lomax, president and CEO, United Negro College Fund; Mark Lomax, Mia Lomax, and the entire Lomax family for their help and support of this project. For anyone I have inadvertently omitted, please charge it to my head, and not my heart.

Preface: “Passionate Attachments” as Creative Motivation

It is essential for me as a researcher to identify my own standpoint and passions in undertaking this project, as they are its catalyst (Royster, 2000).

As an African American woman who has worked as a newspaper journalist, I am interested in other African American women of this professional and personal background. Particularly, I have long held an interest in those African American women journalists who have come before me, such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett. In fact, I was so interested in this particular journalist, even after leaving newspaper journalism in 1999, that I researched, wrote and performed an original dramatic monologue, “Through Voice and Pen: Ida B. Wells-Barnett and the First Amendment,” as an entry in the 2003 Women in Communications Edith Wortman public speaking competition, placing second nationally. I initially planned on Wells-Barnett as a dissertation topic, but later discarded it when no one seemed particularly excited about it—I wanted people to be interested in my topic, and it seemed that, although those who had heard of Wells-Barnett respected her accomplishments, she did not seem to arouse curiosity. So, by a series of serendipitous and highly unlikely coincidences, I decided on the communication practices of African American women in the sacred harp/shape note singing tradition as my topic. However, as time went by, I found my enthusiasm for this topic waning. I was told, though, that this was a normal occurrence in the dissertation process, so it did not overly concern me. I continued working on completing my Ph.D. coursework persistently, although very slowly, while also working full time and managing family responsibilities.

Then one day during the spring of 2011, while at my hair salon, I found myself flipping through a recent issue of Jet magazine (still then in print), which I did not normally read, when I came across a short obituary of Almena Davis Lomax. My interest was piqued, as the obituary stated she had been publisher of the Los Angeles Tribune, a Black weekly, and the only Black woman newspaper publisher in that city I had heard of up until then was Charlotta A. Bass of the California Eagle. Out of curiosity, I Googled Lomax later that same day, pulling up other Lomax obituaries published in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Associated Press and other major media outlets. Clearly, Ms. Lomax had been no ordinary journalist, but why had I not heard of her before?

Shortly thereafter, I met with a research librarian at Florida State University, my doctoral institution. After several specialized academic searches, we came up with virtually nothing on Ms. Lomax. Intrigued as to why this obviously notable journalist had not been the subject of any major scholarly treatment, I dared to think that she might make an interesting doctoral research topic—one that might possibly even manage to sustain my interest for the duration of the project—unlike my current topic. I told the research librarian how much I would like to study Ms. Lomax right then, but that I already had a dissertation topic, which I had completed substantial work toward. She suggested that I might be able to work on the Lomax project if and when I needed a break from my dissertation. “Think of this project as an affair, and of your dissertation as a marriage,” she advised. Although I deflated at the thought of my dissertation topic, I agreed that this was a sensible course of action.

Later, I happened to mention my find to my mother, who said, “I haven’t seen you this excited about anything in a long time.” I then allowed myself to seriously consider the possibility of changing my topic—I might have to complete additional course work, which would result in my taking even longer to finish the degree. But then I reasoned that it was already taking me a long time, anyway—what would a few more months, or maybe even another year, really matter, in the long run?

I talked with my then-dissertation chairman about it, and he said I probably would not need to complete any more coursework, but that I might want to tweak my committee composition if I changed topics. He seemed as enthused about the possible change as I, which encouraged me to talk with a new potential chairman, who soon agreed to assume this role in my revised committee.

All this took place in May 2011. The next month, I happened to again be at the hair salon when the professor whom I had been considering asking to be my outside committee member just happened to be there as well. Although I already knew of her, of course, I did not know her personally. I took it as a sign—I mustered up my courage, knowing she did not know me from Adam, introduced myself, and asked if I could meet her for coffee to talk about my project. Shortly thereafter, she, too, agreed to serve on my new committee. Changing my dissertation topic has proven to be one of the best decisions I have ever made.

Examining Lomax’s work is indeed a “passionate attachment” (Royster, p. 280) from my standpoint as an “embodied” African American woman writer and former journalist. From within Royster’s Afrafeminist framework, I perceive my “commitment to social responsibility” as the goal of, while acknowledging any potential bias I may have as the researcher, revealing my subject on her own terms, allowing her work to speak for itself. I perceive that her work is valuable and should “count as knowledge.” As Royster contends, the reader should rightly consider my “passionate attachments” and commitment to social responsibility as my creative motivation in pursuing this project.

Afrafeminist ideology may thus be a useful theoretical orientation from which to examine Lomax’s work in that she fits the criteria of “elite” status Royster articulates: She was a professional journalist; the Lomaxes were well known and respected in the Los Angeles African American community— particularly because of their ownership of the Dunbar Hotel, which was owned by Lomax’s father-in-law, Lucius Lomax, Sr.; Lomax was known for her outspokenness and fearlessness in promoting African American interests in her Los Angeles Tribune writings, as well as in her other civil rights activism; and, due to her family and personal positions, she had, perhaps, unusual access to Los Angeles’s White power structure, as well as to the upper echelons of African American society, of which she was part. Finally, because she was not (initially) her family’s sole means of financial support, she was able to devote the time she deemed necessary to disseminate her views regarding the advancement of African Americans via her writings and other forms of advocacy. Also, by disclosing my passionate attachments and commitment to social responsibility regarding this project, as suggested by Royster, I give the reader the information they need to properly assess this project.

Further, with Afrafeminist ideology, Royster suggests that:

We can see how these women [African American women writers] with their unique voices, visions, experiences, and relationships have operated with agency and authority; defined their roles in public space; and participated in this space consistently over time with social and political consequence. Using this type of approach, with a group that by other lenses has been perceived as inconsequential, we have a provocative springboard from which to question what “public” means, what “advocacy” and “activism” mean, what rhetorical prowess means. (Royster, 2000, p. 284)

Introduction

If somebody called me the N word, if someone didn’t treat me right, I had a muck-racking, hell-raising journalist mother who would give them … I mean, they didn’t do that. She is writing, all by herself, a 20-page tabloid weekly, the Tribune. That was a trouble-making paper. We fought against capital punishment. Throughout the ’50s, when people were blacklisted, and couldn’t write for some newspapers, they came to write for us. When the bus boycott hit, she went to Montgomery, and that changed her life. She decided, “This is the story of my life. I’m going to convince my husband and family to move south.” (Greenfield-Sanders, Michael Lomax interview, The Black List, Volume 3, HBO, 2009)

While African American women journalists’ contributions to America’s long civil rights struggle via their writings and speeches, particularly those of the nineteenth century, early twentieth century, and late twentieth century, have received greater attention in recent years (Bay, 2010; Broussard, 2002, 2004, 2006; Davis, 2012; Gaines, 1994; Giddings, 2009; Gilliam, 2019; Guy-Sheftall, 1995; Hunter-Gault, 1992, 2012; Lloyd, 2020; Logan, 1995, 1999; Nelson, 1997, 1993; Reynolds, 1998; Rhodes, 1992, 1998; Richardson, 1987; Royster, 1997, 2000; Schecter, 2001; Streitmatter, 1994; Roessner and Rightler-McDaniels, 2018; Walker, 1992), there is yet much to glean from other Black women journalists who also built upon the path set by journalist-activist foremothers such as Maria W. Stewart, Mary Ann Shadd Cary, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Anna Julia Cooper, and others—African American women newspaper publishers/editors of the mid-twentieth century. Marzolf (1977), in Up from the Footnote: A History of Women Journalists, states:

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 284

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433198083

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433198090

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433198069

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433198076

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20662

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (February)

- Keywords

- Biography Journalism Communication History Media Women Women Journalists African American Civil Rights Twentieth Century Frontierswoman A Rhetorical Biography of Almena Davis Lomax, Journalist Chandra Snell Clark

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, Oxford, 2024. XVIII, 284 pp., 11 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG