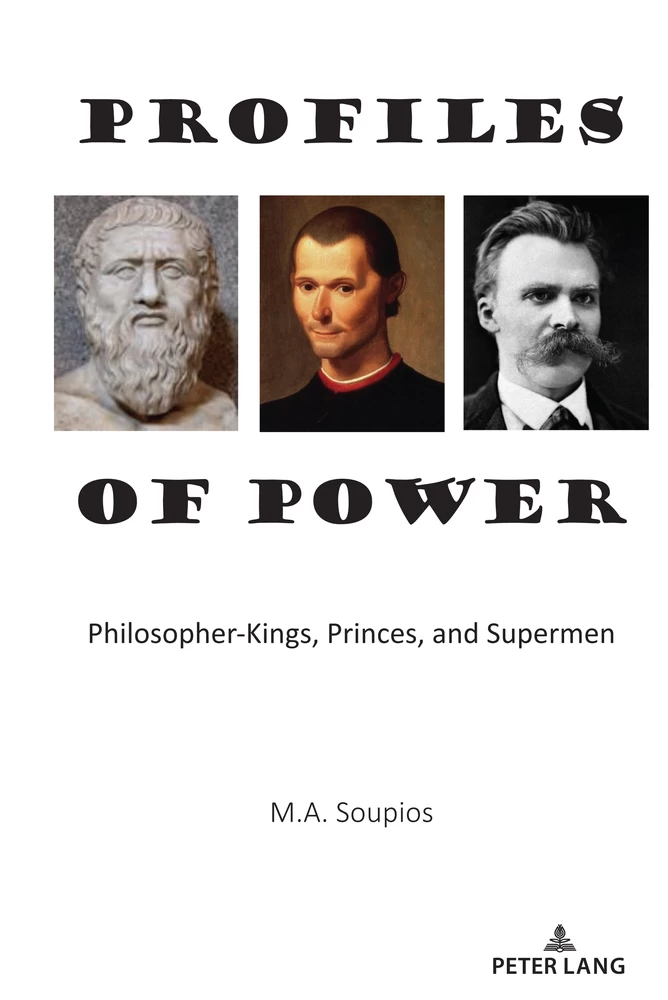

Profiles of Power

Philosopher-Kings, Princes, and Supermen

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Acknowledgments

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Plato -- The Philosopher-King

- Chapter 3 Machiavelli -- The Prince

- Chapter 4 Nietzsche - The Übermensch

- Chapter 5 Final Reflections

- Chapter 6 Appendix: Charisma

- Chapter 7 Bibliography

- Index

About the author

M.A. Soupios (Ph.D., Fordham University) is Professor of Political Science at Long Island University. His publications include The Song of Hellas (2004), The Greeks Who Made Us Who We Are (2013), and The Ten Golden Rules of Leadership (2015).

About the book

Profiles of Power: Philosopher-Kings, Princes, and Supermen examines the concept of “power” in the form of three iconic personifications: Plato’s Philosopher-king, Machiavelli’s Prince, and Nietzsche’s Superman. It demonstrates how these thinkers’ response to power was determined by their investigation of the fundamental nature of humankind, the limits of human understanding, and the question of whether the universe is a rationally ordered domain or an unscripted chaos. Given the widely variant settings in which these men lived, their responses are understandably diverse. But author M.A. Soupios suggests that at least one concern unites their thoughts and purposes: that dangerous times necessitate the services of rarefied human types, and that charismatic leadership is a necessary countermeasure against the dissolute tendencies of culture and community. As Soupios argues, it is specifically in these salvational terms that the celebrated power archetypes advanced by Plato, Machiavelli, and Nietzsche must be understood.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Undertakings such as these are, without exception, collaborative endeavors. The author may conduct the research and construct the narrative, but he does so in conjunction with the aid and encouragement of family, friends, and colleagues. In this regard, a major note of gratitude is owed to Professor Edmund Miller, a most gifted wordsmith and grammarian. Sadly, the breath of life no longer resides in this gentle soul, but the generous insights he extended these pages remain a testimony to his talent and goodness. In addition, I am beholden to Dr. Kay Sato who provided essential remedy to a variety of syntactic missteps that might otherwise have gone undetected and unrectified. I am pleased, as well, to note the generous contributions of my former student (both graduate and undergraduate), Ms. Poulos. Here, I proffer thanks in Virgilian terms. For more than a decade, Diana’s technology skills have served as my Golden Bough. Minus her expertise, this technologically inept Aeneas would have wandered aimlessly in a cybernetic netherworld.

Finally, and above all, I offer special thanks to my wife Linda. As keeper of the family calendar she has, throughout the years, dutifully arranged the one asset most essential to academic life—free time. Be it noted, as well, these accommodations all too often came at the expense of her own convenience and preferences. Needless to say, words of appreciation hardly suffice.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 2 Plato -- The Philosopher-King

Chapter 3 Machiavelli -- The Prince

· 1 ·

INTRODUCTION

Power is an intrinsic feature of nearly every human relationship and activity, which explains the many references to it across a wide range of endeavors. For example, we routinely speak of economic power, political power, executive power, military power, purchasing power computing power, etc. As one might expect, the concept of power has also been a continuous object of study and analysis from antiquity (e.g., Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue and Plato’s portrayal of Thrasymachus) to modern times (e.g., Bertrand Russell 1938; A.E. Berle 1969; Bertrand DeJouvenel 1993; Hannah Arendt 1970; J. K. Galbraith 1984). In short, power is a leitmotif that has long inspired the interests of historians, philosophers, sociologists, economists, psychologists, and political scientists alike. Moreover, despite divergent approaches and priorities distinguishing these myriad inquiries, they all share at least one common feature, viz., a consistent acknowledgement that no important facet of human experience can be accurately understood without considering the pervasive influences of power.1

At the same time, however, the learned investigations of philosophers and social scientists are generally irrelevant to the simplifying tendencies of popular imagination. When, for instance, the average person considers the term “power,” the majority tend to think of one thing, and one thing only—so-called “naked power.” The images encompassed by this phrase involved a sliding scale of violent activities ranging from the indiscriminate carnage on battlefields to the more precise agonies of dungeons and torture chambers. But in all cases, what these portraits of naked power tend to share is a vision of asymmetrical relationships in which some group or individual aggressively dominates another. These violent depictions have also been powerfully reinforced by a series of colorful narratives describing, and in some cases advocating, the realities of naked power, especially in the political domain. Obvious illustrations include works such as Machiavelli’s Prince, where we are reminded that the necessities of power know no limits, and Leviathan where Hobbes describes a war of “all against all” in a struggle for power that “ceases only after death.”

But as commonplace as these images and admonitions may be, many of them remain misleading simplifications, often concealing and distorting the true complexities of power. Modern research has convincingly demonstrated that there is more to the notion of power than tear gas canisters and rubber truncheons. As a descriptive category, the term “power” is far more intricate, multifaceted, and subtle than anything indicated by the phrase “naked power.” Among other things, power must be understood as an omnibus concept comprised of related, but nevertheless distinguishable, sub-categories. Words such as force, violence, authority, etc…, are certainly cognates, but the colloquial tendency to conflate these terms invariably obscures a variety of substantive distinctions. Take, for example, the reflexive tendency to synonymously employ words such as “violence” and “power.” As Arendt notes (51, 56, 87), violence is an instrument, a device for enhancing strength. When those holding power believe their grip is slipping, violence is employed as a means of reversing a presumptive loss. Viewed in these terms, violence is clearly distinguishable from power per se. Violence is better seen as an indicator of power’s fleeting essence and, more specifically, as an aggressive response to a perceived decline of command and control.

Another aspect of power critical to an accurate understanding of its complexity involves the associated ideas of legitimacy and persuasion. It goes without saying that power is, by its very nature, a relational phenomenon. There are, as D.H. Wrong suggests (2004:49), “power holders” and “power subjects” and, as these designations imply, the former group enjoys hegemonic prerogatives based on a capacity to bestow punishments and rewards. This imbalance notwithstanding, power holders rarely exercise anything approximating absolute control. Even the most coercive relationships tend to include varying degrees of counterinfluence exercised by subordinates (Wrong 48–49). And it is specifically this reciprocal dynamic that makes legitimation an important concern even for despots because bayonets alone are unlikely sources of approbative loyalties.2 Indeed, one could argue that violence rarely if ever secures enduring conformity and under certain circumstances it may even diminish or destroy power (Arendt 56). As a consequence, even the autocrat needs to foster the perception that his “might” is somehow constitutive of “right.” Those able to secure this mode of approval reap the benefits of “authority,” i.e., subordinate endorsement whereby the leader is deemed worthy of respect and compliance. Two distinct advantages accrue to such legitimated individuals, neither of which is generally available to those relying exclusively upon the iron fist. First, legitimated power tends to be more efficient in a managerial sense, to the extent it minimizes the need to constantly surveil and impel a given population. When properly established, legitimacy offers the opportunity of converting mandated labors into willingly accepted tasks. In addition, there is evidence to suggest prolonged oppression tends to lose its sting, that those routinely subjected to imperious constraints become inured to such treatment over time.3 In short, by reducing the need for dictatorial supervision, legitimacy not only offers administrative economy, it may also help maintain the viability of violent threat, in the event such gestures become necessary.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 174

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433198991

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433199004

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433198984

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20091

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (July)

- Keywords

- Power Politics Greek Philosophy

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2023. XII, 174 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG