The Land Between

A History of Slovenia

Summary

Dejan Djokić, historian, National University of Ireland, Maynooth

A study which makes the reader feel and understand that since the end of the Cold War there is a new lease of life for Central Europe. The former borderlands between East and West construct their new identities. Slovenia is one of the most successful new democratic societies in the middle of Europe. This book is an excellent history of Slovenia which maps the narrative of a small European people without falling into the traps of national mythmaking. Writing about a small European country with two million inhabitants which crave for Central European, Mediterranean and Balkan traditions at the same time is no simple task. The book makes fine reading for everybody interested in understanding the fascinating and creative complexities in the heart of Europe. Highly recommendable for history lovers and historians alike!

Emil Brix, historian and ambassador, Director of the Diplomatische Akademie

Wien – Vienna School of International Studies

The book presents a concise and intelligible history of the Slovenes. The authors take into due consideration the history of the territory between the Eastern Alps and the Pannonian Plain, starting with the period that began long before the first Slavic settlements. Thus, they wish to emphasize that the Slovenes’ ancestors did not settle an empty territory, but rather coexisted with other peoples and cultures ever since their arrival in the Eastern Alps. This has enabled them to build a community shaped by countless influences stemming from a long period of living alongside German, Romance, and South Slav neighbors in a melting pot of languages, cultures, and landscapes.

The same reasons have most probably also contributed to the perception of their land as a “land in between.” Constituting a link between Eastern and Western Europe, Slovenia has recently also been increasingly perceived as the meeting point of Central Europe and the Balkans. Today, history still occupies the central position in the life of the Slovenes. The heroic period of emancipation has been completed and the Slovenes will be bracing themselves for a no less turbulent period of challenging “essentialist” notions of identity in order to create a thoroughly open society.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- From Prehistory to the End of the Ancient World

- History Created by Archaeology

- The Roman Empire: Conquest and Pax Romana

- From the Marcomannic Wars to the Settlement of the Slavic Tribes

- The Early Middle Ages

- The Carolingian Period of the 9th Century

- Feudalism

- Reorganization of the Marches and a Shift of Ethnic and Language Borders

- From Autonomy to the Unification of the Alpine and Danube Basin Regions

- “Tres Ordines Slovenorum”: Society, Economy, and Culture

- The Stars of Celje

- The Bloody Fall of the Middle Ages

- The Early Modern Period

- From Humanism to Reformation

- From Counter-Reformation Rigor to Baroque Exuberance

- Scholars, Officials, and Patriots Changing the World

- Modernization and National Emancipation

- French Rule

- The Pre-March Era, the Time of Non-freedom

- “The Year of Freedom,” the 1848 Revolution, and United Slovenia

- The Slovenes in the Constitutional Era

- Unity and National Existence

- In the Shackles of Political Parties

- The Other Side of History: Herstory

- From the Habsburg Monarchy to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

- Divided by the Great War

- The Making of the New State

- The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

- Dictatorship and the Crisis

- “A Nation Torn Apart”: World War II in Slovenia

- Slovenia after the Liberation: The “People’s Republic” and the Time of Socialism

- The Establishment of the “New Order”

- The First Five-Year Plan and Self-Management

- “Liberals” vs. “Conservatives”

- From Crisis to Conflict and Beyond

- History Does (Not) Repeat Itself

- Epilogue

- A Note on Pronunciation and Regional Toponyms

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- Selected Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Preface

We were led to write this book not only because we have yet to see a concise history of Slovenia to date, but also because we have noticed that articles about Slovenia, written mostly by journalists and politicians, often turn out to be inadequate and incorrect.

We acknowledge that—in the wake of the collapse of socialism and after the outbreak of wars in former Yugoslavia—the lack of knowledge about the history of Central and Eastern Europe led to a stream of factual errors and misleading interpretations. Their repetition led to new misinformation and questionable analysis, which only added to the existing confusion. Our aim in this book is not to clarify and correct these interpretations, but to provide a detailed and accurate scholarly account of the history of our country. We merely wish to describe the events and processes that happened to those who resided here in the past and to those who reside here today.

In an effort to avoid a one-dimensional description of major events and leading personalities, we have discussed parts of this book with many colleagues from Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austria, Great Britain, and the United States. We will not attempt to list their names as any list would be incomplete. However, we hope that we have acknowledged the most important contributions through quotations in the text. Nevertheless, there are still a few people who cannot be omitted. Following the chronology of the book, we would like to thank Breda Luthar, Ivan Turk, Janez Dular, Rajko Bratož, Dejan Djokić, Emil Brix, and Peter Vodopivec.

The authors of this book would also like to thank Mateja Belak, Manca Volk Bahun, and Iztok Sajko for creating the maps, our translators Manca Gašperšič, Olga Vuković, Alan McConnell-Duff, and Paul Towend for their hard work, our copyeditors Catherine Baker, Damjan Popić, Hanna Szentpéteri, Miha Zemljič, and Tadej Turnšek for their invaluable contribution to improving the language of our manuscripts, Jean McCollister for her proofreading, and Hanno Hardt for his editorial comments. The only way to thank them properly is to paraphrase the words of Ivo Andrić: The work of a good translator sometimes borders on magic, and seems like real heroism.

The authors,

Ljubljana, 2024

Introduction

In the summer of 2002, a large, interactive map of the world was installed in front of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The map was made up of several small pieces that resembled a giant jigsaw puzzle. Since it was part of a playground in front of a London museum, only children were allowed to access it. In fact, the map was designed for them. They were encouraged to learn, whether from it or on top of it. They were supposed to educate themselves about the countries of the world from the installation, such as their size, shape, and location. The idea itself was brilliant, but, unfortunately, the designers of the map made some minor mistakes. As it often happens, the curators of the museum divided the countries into more important and less important ones.

This mishap seemed to have happened due to technical reasons. Since the map also included pictures of the most famous cities, the mapmakers were simply running out of space. So, they just covered Slovenia with a photo of Venice, since Venice seemed much more important than a tiny country that no one really knew. And just like that, just like many times before, Slovenia’s more influential neighbors spread across the country, this time metaphorically.

Having already had the idea of writing a book about the history of Slovenia, we quickly realized that our main task would be to make visible that tiny portion of the map where the average connoisseur of European history and geography would expect to find pieces of Italy or Austria. In order to do this, we decided to include certain Central European countries which have had a decisive influence on the form and shape of Central Europe in modern history. We concluded they could be used to present the history of our country as an integral part of that area.

Later on, once we started writing the book, we found ourselves encountering the same situation again and again. When working on our respective chapters, each of us would find Slovenia, or the Slovenian lands, as a representation of a region or space between two different worlds, an extension between Europe and its periphery. We also encountered this extension in the views of the foreigners who have described this area. These people have experienced the Slovenian lands as distinct from other surrounding areas. From their point of view, the landscape, temperament, history, tradition, and language were different from everything else in that same region. At first glance, they compared it to “Switzerland or the Tyrol,” until their “closer inspections” showed them that the temperament was Slavic. The language was similar to Serbian or Croatian, but with noticeable differences. It was observed to be more archaic and complicated, and far more difficult to learn.

Nevertheless, the most puzzling concept for foreigners to understand is Slovenian history. Most people who are interested in the past find it hard to recognize the fact that Slovenians survived so many centuries of foreign rule. Therefore, we decided to depict the history of Slovenia as a history of a particular place, especially when dealing with the prehistoric periods and the time before the arrival of the Slavs. Well aware of the usual brief and superficial description of this period, we decided to present it in its full complexity as comprehensively as possible. For us, this is also a way to show that the Slavs did not settle in an empty space and simply replace the Celto-Roman inhabitants of the earlier times. They were first mentioned by Roman historians as early as the mid-6th century. However, it is only from the 9th century onwards that Medieval historians have been in a position to give these neighboring communities particular names (which they are still known by today), instead of lumping them all together into one generalized Slavic group. However, these writers envisaged them as ready-formed peoples, whereas the reality is more complex. Their formation was a matter of reciprocal acculturation.

We approached the later periods in a similar manner, which is why the Slavic territory is not depicted as a typical frontier march under various margraves. We also tried not to portray them as expendable defenders of the empire against the threat of the Hungarians, sometimes other Slavs, and later the Ottomans. We also do not believe that the Slovenians only made two important appearances in history throughout the entire feudal era. Namely, a brief period of glory under the Counts of Celje as well an early revival of national sentiment and language during the Reformation.

Similarly, in the later periods, especially in the 20th century, most Slovenians joined the resistance movement against the German, Italian, and Hungarian occupation during World War II. Later on, they gained independence without being dragged into the wars that accompanied the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

Our goal with this book is simple: instead of a briefly outlined overview, we offer a concise but complete history of the Slovenian people, thereby affording the reader a perspective that goes beyond the stereotypical depictions of the area. In short, we wish to explore the 2,000-year history of the different dominant ruling cultures in the modern Slovenian territory, and what was hidden beneath their administrative surface. In other words, we wish to present you with a history of the place beneath the aforementioned photo of Venice, for all the readers who wondered what was hiding underneath and for all those who are interested in the history of one of Europe’s smallest countries.

History Created by Archaeology

The Ice Age and the Decline of the Hunter-Gatherer Community

The history of any country should reach back to the very first traces left by humankind. In the territory we now call Slovenia, this is most likely the end of the Lower Paleolithic Age (c. 250,000 years ago). Some rare stone artifacts from that period are known to originate from the caves Jama v Lozi and Risovec in the Pivka Basin. The Pivka Basin, rich in water sources, food for animals, and the raw material suitable for stone knapping, was an attractive living space for Paleolithic hunter-gatherers. It is therefore not a coincidence that this is an area with the highest frequency of Paleolithic sites in Slovenia.1

While no fossil remains of Pleistocene hominins have been confirmed to date in Slovenia, Neanderthals (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) and anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) left many traces of their presence nevertheless.2 The Neanderthals lived in Europe during the Middle Paleolithic (250,000 to 40,000 years ago), before they became extinct and were replaced by modern humans. The Middle Paleolithic sites in Slovenia are mainly found in caves and are between 120,000 and 40,000 years old. At that time, the Mousterian culture, attributed to the Neanderthals, was at its height. Interestingly, Neanderthals had visited those same caves from time to time without being aware of any predecessors, although they used the same routes and pursued similar goals throughout the millennia. This was especially true for the multilayered Paleolithic cave sites Betalov spodmol in the Pivka Basin and Divje babe I near Reka in the Idrijca river valley.

Caves were a natural shelter for both Paleolithic hunter-gatherers and cave bears. Neanderthal tools have often been found alongside cave bear remains which has in the past led to the conclusion that Neanderthals were specialized hunters of this mighty beast. However, newer findings and data obtained during systematic archaeological excavations of Divje babe I has allowed archeologists to at least partially understand the Neanderthals’ way of life.3 While many hearths have been preserved in the cave, only rare remains of hunted animals such as marmots, wolves, brown bears, chamois, and roe deer have been found around them. The Neanderthals visited Divje babe I mostly in search of limb bones and cave bear skulls. They crushed them in order to reach the nutritious bone marrow and brain. In the colder seasons of the Last Glacial Period, Neanderthals also sought shelter in the cave and might have then encountered cave bears that regularly used caves as hibernation dens. There may have been some competition for shelter between man and beast, although little is known about this. Interestingly, Neanderthals and cave bears, both highly adapted to Ice Age conditions, became extinct before the Last Glacial Period reached its peak, while anatomically modern humans and the brown bear—two far less specialized species—survived.

At Divje babe I, characteristic Neanderthal tools such as scrapers and denticulated tools were present for a very long time—from the Last Interglacial Period (c. 115,000 years ago) until their extinction—which suggests that tradition played an important role for the Neanderthals. Nonetheless, they were also innovative and were already working with bones to make a unique bone musical instrument. This approximately 60,000-year-old bone musical instrument (known as the Neanderthal flute) is the oldest wind instrument in the world to date (Fig. 1).4 This outstanding Slovenian Paleolithic find utterly transformed deeply rooted conservative conceptions of Neanderthals’ cognitive abilities, since until then they had not been credited with even the most rudimentary artistic skills up until that point. This Neanderthal musical instrument sheds a new light on both our extinct predecessors and on the origin of music. Divje babe I is also an invaluable cave site because it is the only Paleolithic site in Slovenia where cultural finds of the late Neanderthals and early anatomically modern humans have been found.

Figure 1.Neanderthal musical instrument from Divje babe I.

During the early Upper Paleolithic (c. 40,000 to 30,000 years ago), modern humans, bearers of the Aurignacian culture, settled the present-day Slovenian territory. Characteristic finds of the Aurignacian are bone points, which were hafted on wooden shafts and used as spears. An outstanding number of bone points, more than 130, were found in the cave Potočka zijalka (1,675 m) on Mt. Olševa, the first Paleolithic site discovered in Slovenia and excavated by professor Srečko Brodar between 1928 and 1935. In addition, one of the world’s oldest bone needles has been found at Potočka zijalka and several perforated cave bear mandibles, interpreted as flutes.

A large quantity of cave bear remains was found at Potočka zijalka, as well as the enigmatic teeth of a musk ox—a characteristically arctic animal—and, more recently, the teeth of another arctic species, the wolverine.5 Another important Aurignacian Alpine site is the cave Mokriška jama (1,500 m) on Mt. Mokrica, which was a typical cave bear den. In comparison to Potočka zijalka, Mokriška jama yielded only a scarce number of bone points and stone tools.

The Aurignacian was followed by Gravettian culture (30,000 to 20,000 years ago), which saw great prosperity of artistic expression in Europe. Higher population density and increased mobility accelerated the cultural and technological development of anatomically modern humans.

The Late Upper Paleolithic or the Epigravettian (20,000 to 11,500 years ago) was characterized by fast changes in the natural environment, such as glaciation, warming, extinction and the retreat of some animal species. Significant cooling approximately 20,000 years ago caused the last great advance of continental ice and Alpine glaciers, which forced the human population and animals from the affected area to move to the south. The Paleolithic hunting-gathering economy was at its height, and composite hunting weapons became widely used. Characteristic finds of this period are backed bladelets and points that served as barbs fastened to the tips of wooden spears. Pronounced microlithization of stone armatures indicates the invention and use of a bow. The richest Epigravettian cave site in Slovenia is the Ciganska jama, a cave near Kočevje, where the marmot and reindeer were the most haunted animals. Among the open-air sites it is worth mentioning Zemono near Vipava, where two engraved stones were found, a rare example of Paleolithic artistic expression found in Slovenia.

Some 11,500 years ago, the Last Glacial Period was followed by rapid warming and forest expansion. This period of time conventionally refers to the end of the Ice Age (Pleistocene) and the beginning of the Holocene, the current geological epoch. It also marks the beginning of the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age). The transition from the Paleolithic to the Mesolithic is not well known in Slovenia, and Mesolithic sites are generally poorly researched. Breg pri Škofljici, Pod Črmukljo, Mala Triglavca, and Viktorjev spodmol are among the most significant ones. Much like in the Paleolithic, people still did not have permanent settlements, and subsisted largely by hunting forest animals, such as red deer and boar. The bow became the main hunting weapon. Among lithic tools, microlithic artifacts of geometric forms predominate, particularly scalene triangles and trapezes, which were attached to the tips of arrowheads. By the end of the Ice Age, people began to exploit the mountain environment yet again, as evidenced by numerous open-air sites recently discovered in the Julian Alps in the Upper Soča Valley. At this time, wolves began to be domesticated and the first dogs appeared. After the Mesolithic, people began to turn to farming and raising livestock.

Herders and Agriculturalists of the Neolithic and Copper Ages

The end of the Ice Age brought about great change: the sea encroached on what had been the continental bay of Trieste up until that time, glacial lakes emerged in the Alps, and flora and fauna were altered. People began to establish permanent settlements, and with that, their population numbers increased greatly, since cultivation and animal husbandry provided extra food supplies. This development marked a major advance, perhaps even a revolution, in the Neolithic period. People began cultivating specific types of grains, such as wheat and barley, and raising domesticated animals such as goats, sheep, pigs, and cattle.

We now know that the Middle East had already been taken over by Neolithic man by the 8th millennium BCE, even though early evidence places agriculturalists in Greece early in the 7th millennium. Inhabitants of the upper Danubian region cultivated the land during the 6th millennium and made ceramic dishes, which they decorated with uniform patterns. Around that time, a Neolithic population inhabited the central Balkans, characterized by the Vinča culture and named after the Serbian site of Vinča, near Belgrade. Influences from the Carpathian basin and the eastern Adriatic coast also reached Slovenian territory. The oldest open settlement discovered so far is located in western Slovenia, in the foothills of Sermin near Koper—more precisely, the region of Capris, present-day Koper—and dates from the 6th or early 5th millennium BCE. Thus far, the only other finds from the oldest Neolithic are from the caves of the Karst hinterlands of Trieste. This area was probably still settled by hunters, who came into contact with herders from the Gulf of Kvarner and Dalmatia, from where sheep and goat herders brought Danilo ceramics and Hvar pottery to the Karst region. The ceramics are named after Danilo, a site near Šibenik, while the pottery is named after the island of Hvar. The Sermin site suggests that the herders had settled permanently in the littoral. Interesting information about the Eneolithic (Copper Age) in western Slovenia comes from cave sites (at Mala Triglavca and Podmol near Kastelec), which were still the main shelters for people who mostly raised livestock and hunted. Zoological and botanical studies provide evidence that herdsmen spent some time in several of the caves. The remains of sheep and goat feces in caves, the presence of grass pollen in the Neolithic cultural strata at Podmol, as well as the presence of mixed oak forest and typical pasture vegetation all indicate that herds grazed near the cave. Bones provide further evidence that sheep, goats, pigs, and domestic cattle were raised.

Stone tools of the time were mainly fashioned from local stone;6 the finds of crucibles (vessels used for smelting) indicate that Copper Age metal workers probably smelted the ore in open fireplaces. By blowing, they could increase ventilation and thus accelerate the smelting process. Ventilation aids included elongations for bellows and blowpipes. The oldest copper finds at Slovenian sites are from the first half of the 4th millennium BCE and include axes and daggers, which were probably fabricated in the Middle East. Domestic crafts began to develop somewhat later, as evidenced by the remains of smelting vessels with traces of copper, which originated in the mid-4th millennium BCE and are from Hočevarica in the Ljubljansko barje (Ljubljana Marshes). Remnants of a clay mold from the late 4th millennium BCE were found at the Maharski prekop (Mahar Canal). Single and double-part clay molds for small hatchets and clay vessels for molten metal from Dežman pile dwellings (Dežmanova kolišča) date back to the 3rd millennium BCE, i.e., the Late Copper Age, a time when metalwork was becoming more firmly established in present-day Slovenia. Nozzles for blowpipes and air bellows have also been found here, specifically in the pile dwellings at Špica by the Ljubljanica river in Ljubljana. The pile dwellings near Ig in the Ljubljana Marshes (Fig. 2) were first researched in the late 19th century by Karl Dežman (Deschmann), the curator and later director of the Regional Carniolan Museum in Ljubljana (the modern day National Museum of Slovenia). This period is characterized by the settlement of people belonging to the Vučedol culture (named after a site in northern Croatia), whose presence has been documented mainly on the Ljubljana Marshes.

Figure 2.Pile dwellings on the Ljubljana Marshes.

Herders and livestock breeders did not settle in the interior of Slovenia, where only hunter-gatherers had previously lived, until the 5th millennium BCE.7 The new population settled on promontories above rivers (such as the town of Moverna Vas near Semič), along river bends, in caves, by lakesides and in marshlands, as well as on hills. They also had hillfort settlements (such as Gradec near Mirna), fortified by stone enclosures. A burial site, which marks the transition from the Late Neolithic to the Copper Age, was discovered at the cave Ajdovska jama, near Nemška Vas, and close to Krško, in the easternmost part of the Lower Carniola (Dolenjska) region. The cave has two entrances and a complex ground plan with several shafts. The dead were placed upon the cave floor according to a predetermined arrangement and usually surrounded by a circle of stones. Beside them various vessels, bracelets, pendants, and necklaces, as well as stone axes and arrowheads. Corn-filled vessels, various animal bones, and fireplaces suggest burial rites, which included eating at the site or offering food to the dead. Anthropologists have since identified the remains of 31 individuals: 7 men, 8 women, and 16 children.

Most of the known sites from the 4th and 3rd millennia BCE are found in the Ljubljana Marshes, whose inhabitants had maintained contact with Central Europe, the Pannonian Plain, Caput Adriae, northern Italy, Dalmatia and Balkan regions. Some finds even indicate a connection with eastern Europe and the inhabitants of the steppes. In the early 3rd millennium BCE, members of the Vučedol culture also started to establish permanent settlements in the Ljubljana Marshes and elsewhere in the area of contemporary Slovenia (specifically Vinomer, above Metlika, and the Ptuj Castle), but not in the Trieste Karst, where artifacts have been discovered in caves. The pile dwellings in the Ljubljana Marshes were an exceptional discovery. Over 40 of them from various time periods have been unearthed in the past 145 years, and even the imperial court in Vienna was interested in Dežman’s excavations. The reason for these pile dwellings was probably the desire for security.8

A characteristic feature of the lake dwellers is their beautifully decorated earthenware of good quality, which is indicative of creative, artistic practices. Clay spindles, bone needles, and remnants of threads reveal that women wove and sewed. Wool must have also been in use, as is indicated by the remnants of sheep of a suitable age and size. Interesting patterns on the ceramics, particularly on anthropomorphic statuettes, may suggest the type of patterns on women’s dresses. Statuettes, together with beautiful vases, are the most striking relics from that time (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.Anthropomorphic clay statuette from Ig on the Ljubljana Marshes.

The transition from hunting-gathering to the cultivation of land was accompanied by a continuation of gathering as well as hunting and fishing, although grazing and dairy farming also became increasingly important.9 Indeed, food remains indicate that people ate not only fish and shellfish, but also stag, deer, wild boar, and even bear. Buffalo and bison were eaten too, though their remains are rarer. People also gathered forest fruits and nuts, while grape pips were found at several pile dwellings in the Ljubljana Marshes. The remains of harpoons consisting of three parts (a wooden shaft, a bone extension, and a horn-tipped prong), used for hunting beavers, otters, and larger fish, were discovered near the village of Ig. Inhabitants undoubtedly cultivated the land, as indicated not just by the permanent settlement but also by stone hoes, millstones, and harvest knives. Charred wheat grains have also been uncovered, as have cultivated plants like wheat and barley, and the remains of large clay pots, in which they probably preserved their food.

The lake inhabitants of the time also used simple, hollowed-out canoes, known as logboats, which have been found in considerable numbers. Besides the logboat, remains of one of the oldest wooden carts (a wheel with an axle) in Europe was found on the site at Stare Gmajne, dating from the late 4th millennium BCE. According to radiocarbon dating, the largest number of logboats belongs to the 1st millennium BCE, yet logboats from Stare Gmajne were in use ever since the 4th millennium BCE. Pile dwellings disappeared in the mid-2nd millennium BCE, most likely because the lake gradually drained and became marshland.

The Flourishing of Metallurgy in the Bronze Age and the First Hillforts

During the Early Bronze Age, between the 22nd and the 16th century BCE, the Ljubljana culture reached its height and spread into the littoral region and along the coast to southern Dalmatia. However, its decline at the end of this period has not yet been fully explained. The transition to the 2nd millennium BCE was certainly not as important a turning point in central Slovenia as it was in the Aegean regions, where society was already based on a more highly developed economy. People in the Aegean regions became socially stratified and lived in cities as this was the age of the blossoming Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. In the Danubian region, the population enjoyed a higher level of development as well, due to ore deposits in the Carpathians and contacts with more developed cultures.

At that time, the Slovenian regions were on the sidelines of a changing cultural landscape. During the Middle Bronze Age, between late 16th to 14th century BCE, two characteristic cultures had settled in the region. A population that buried its dead in barrows lived in northeast Slovenia (Styria). Their settlements were located in the lowlands and on the hills. Their material culture (which has been poorly researched) was characteristic of Central Europe. To the west, in the Karst region and in Istria, the population known as the Castellieri (written as kaštelirji in Slovenian) cultural group lived in fortified hilltop settlements encircled by defensive stonewalls.

While the settlements in Slovenia have been poorly researched, those in the Trieste hinterland are far better known. It is interesting that the inhabitants of the Karst settlements lived according to the old ways as recently as the late 14th and 13th centuries BCE, and their flat cremation burials (known as the Urnfield Culture) were a significant novelty throughout Europe. The Karst inhabitants faced great changes. One of the most significant and best-preserved settlements is Debela Griža in the vicinity of Volčji Grad, near Komen. It had been reinforced with an imposing double defensive wall in low-lying places and with a single wall where karstic sinkholes protected the settlement. Caves still remained attractive occasional dwelling places for Bronze Age man, for example, at Podmol near Kastelec, and the cave below the Predjama Castle. The Karst dwellers began to bury their dead in flat cremation burial grounds as late as the 10th century BCE. The main finds from the Late Bronze Age and in the area of the Castellieri culture are in the vicinity of Škocjan.

At the end of the 14th century BCE, a different way of life began in Europe as new peoples arrived. The new population lived in a different kind of settlement and in diverse ways, which considerably changed the appearance of the settlement. This is especially visible when looking at the burial of the dead. The dead were incinerated, and their ashes preserved in urns, which were simply interred in the earth without additionally covering the barrow. Their culture was known as the Urnfield Culture.

These sudden changes are difficult to explain. Perhaps they were simply caused by great technological advances, which led to the stratification of society in various European regions. However, as has been said, it was probably large-scale migrations that brought these changes to Europe. These migrations are considered to have caused the decline of the Mycenaean culture in Greece, the downfall of the Hittite empire in Asia Minor, and the fall of various important eastern cities like Troy, Byblos, and Ugarit. Egypt was also threatened; the sources mention people from the sea. However, in 1189 BCE they were conquered by Pharaoh Ramses III.

These new peoples, who cremated their dead, also settled in present-day Slovenia, leaving their traces in Styria, in the Prekmurje region, and in central Slovenia. Among the two most significant settlements are Oloris near Doljni Lakoš, and Rabelčja Vas in Ptuj. These diverse Slovenian sites have yielded various types of bronze axes and bronze jewelry (sometimes intricately wrought), and different, simply shaped ceramic urns and other vessels. In some places, like the cemetery of the Rabelčja Vas settlement, these are the only objects to have been found in graves. The settlements in Slovenia belonged to a culture which was relatively uniform throughout the broad expanse from western Hungary to eastern Croatia and northern Bosnia. However, there were not many settlements in the Slovenian region during the Early Bronze Age.

The end of the 2nd millennium BCE brought about even more changes. New peoples most likely arrived in these parts again and altered the appearances of settlements, although their inhabitants were still recognizable by their flat cremation cemeteries. In the southeastern Alpine area, one may speak of a cultured region only in the Late Bronze Age (specifically, in the late 11th and 10th centuries BCE). Various groups were formed at that time, which did not differ greatly, but had local particularities indicated by their material culture. In Slovenia, along the Drava and Mura rivers, these groups are categorized as the Ruše group (Ruše, Maribor, Ormož), the Dobova group, which was the second largest and was represented by the inhabitants of Posavje along the Sava River, and the third group, in central Slovenia, which encompassed those who belonged to the Ljubljana cultural group (Ljubljana, Mokronog, Novo Mesto). Their burial goods did not essentially differ and indicate that the society of the time was only slightly stratified. However, long-term changes began to occur during the approach of the 1st millennium BCE. These would end in the 8th century BCE, with the onset of the Iron Age.10

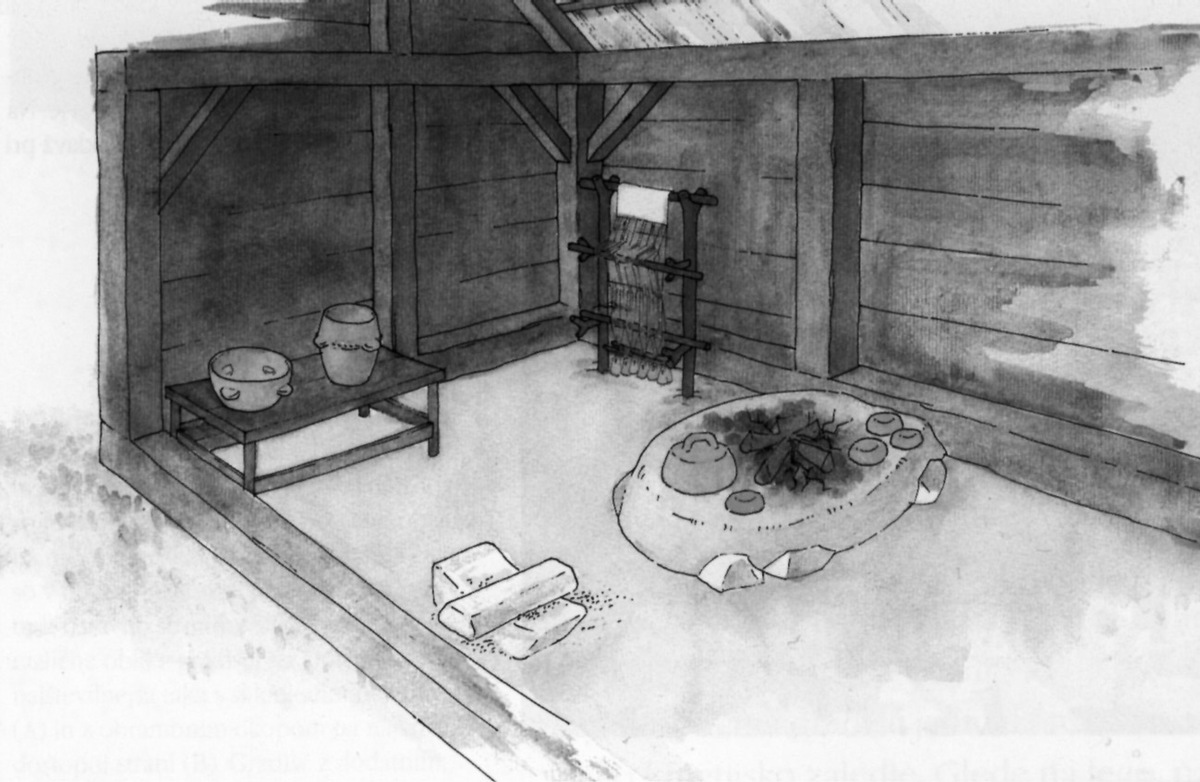

The majority of Bronze Age settlements originated only in the Late Bronze Age, although some had already been occupied throughout the entire Bronze Age, such as Brinjeva gora near Zreče. The houses were, for the most part, wooden, single-room huts: some rested on a stone foundation and featured a clay-covered hearth on the inside. Two important lowland settlements were Oloris (near Dolnji Lakoš) and Ormož.11 Oloris was established in the foothills of the Lendava slopes. This is the first lowland settlement of the middle and Late Bronze Age to have been discovered in Slovenia. The settlement was situated in the bend of a nearby stream, the Črnec, whose moving river-bed left a swamp in its wake. A wooden fence encircled the village. Remains of a wooden conduit for drinking water were found on the settlement’s northern border, in a ditch of the original stream. The walls of the houses, which probably had double-eave roofs, were made of wooden posts, interlaced with branches and plastered with clay. The houses were built close together around a central courtyard, where stoves were placed and around which the life of the settlement revolved. The houses had fireplaces, and pits were dug under the floor to preserve produce. Paleobotanical research has shown that the settlers had cleared the forests to create arable surfaces and had cultivated pastures.

The settlement in Ormož was partly protected by the Drava River and partly by a natural gorge. The exposed sides of the settlement were protected by an earth embankment with palisades and a deep ditch in front of it. This was one of the most significant settlements of the Late Bronze Age in the southeastern Alpine region.12 It was constructed according to a plan, as revealed by the remains of a road network and the remnants of houses alongside it. The houses were constructed similarly to those in Oloris, except that they were larger; one even had two rooms. According to analyses of animal bones, the inhabitants raised livestock, mainly cattle, but also pigs, sheep, goats, and horses. The adjacent burial grounds were also uncovered. The settlement was still inhabited in the Iron Age, but disintegrated after 600 BCE.

Burial customs elsewhere were different.13 Little is known about the cults of those times, except for burial rituals, which are accessible to historians through an analysis of burials and burial objects: vessels are almost always found in graves, as well as jewelry and various other objects. Possibly, the anthropomorphic figurines from Ormož, and various amulets in symbolic shapes (wheel—sun, sickle—moon), which were used as pendants, could indicate the presence of religious ideas at that time.

Bronze Age hoards, especially of tools and weapons, are particularly remarkable.14 They are thought to be the unrecovered property of traveling traders, buried during times of migration and danger. Although their significance has not yet been clearly explained, the prevailing opinion suggests that these were cult offerings by individuals or larger communities who dedicated them to deities and demons. The Karst region of Škocjan, with its renowned Škocjanske jame (Škocjan Caves), as well as other caves in the vicinity, are an expressive natural phenomenon, which itself evokes a religious atmosphere. The people undoubtedly felt that the region of Škocjan was a holy place, while the cave Mušja jama (Fliegenhöhle, Grotta delle Mosche) has since been proven to be a cult site by the discovery of material evidence. The cave, which measures 50 m in depth, was inaccessible to the people of those times, who threw precious objects into the cave, mainly bronze weapons and vessels which they had previously ritually burned. With these offerings, one guesses, warriors were commending themselves to the gods of the underworld. This must have been a well-frequented area, since the objects, which testify to its supra-regional importance, reflect influences not only from the Pannonian Plain but also from Italy and the Aegean world, as well as the western Balkans. The significance of this cult site disappeared almost completely after 500 years, in the 7th century BCE.15 Nevertheless, it was not completely forgotten, as some objects in the cave date back to Roman times.

The Hallstatt Princes and “Situla Art”

During this period (8th–4th century BCE), the tribes that settled in present-day Slovenia remain anonymous, while others in neighboring areas were already known by name: the Histri in Istria, the Iapodes in Lika and in the Una Valley in Bosnia, and the Liburni in northern Dalmatia. This was when the first city states emerged in Greece and when the Greek script developed on the basis of the Phoenician alphabet. It was also the time of Homer’s epics and the decline of the Mycenaean Age, reflected in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Under these remote influences, Central European society underwent a transformation as well: the leading class wielded economic and thus also military power, which promoted universal progress. At this time, ironwork had become one of the most significant branches of the economy. The earlier phase, which ended with the settlement of the Celts, is also known as the Hallstatt period (after the Austrian site of Hallstatt), and the latter is referred to as the La Tène period (after a Swiss site). With the arrival of the Celts, tribes in these parts became known by name for the first time in history.16

During the Early Iron Age, major changes occurred again in settlement patterns, as hitherto unoccupied regions were settled by their original inhabitants or because newcomers from the Danube areas were attracted to these parts by rich iron ore deposits.

Various tribes had settled the lands of what is now Slovenia, yet their material culture indicates that they differed among themselves in settlement structure, burial practices, and in objects for everyday use. The various Hallstatt groups are distinguished as: Lower Carniola (Dolenjska), Inner Carniola (Notranjska), Upper Carniola (Gorenjska), Carinthia (Koroška), Styria (Štajerska) and Posočje (formerly Sv. Lucija, along the Soča River) groups. Speaking of different groups does not necessarily mean that tribes living in a certain area were ethnically differentiated. In our opinion, however, the inhabitants of the Posočje group, who lived close to Italy, were under the Veneti’s strong influence. Their community was among the most developed in modern day Slovenia. The Lower Carniola (Dolenjska) community was also highly developed, judging from the wealth of the finds and from the high degree of social stratification reflected in burial finds and “Situla Art.” In particular, its swift development became possible as a result of its advanced metalworking craft, the most significant economic branch in this community aside from the all-important livestock-raising and cultivation of land. Iron had become so important in the 8th and early 7th centuries BCE that it even replaced bronze in ornament production, although bronze was far more attractive.

In Greece, the Iron Age had already begun in the mid-11th century BCE, while ironwork only began to flourish in modern day Slovenia in the 8th. Earlier, iron objects were imported, including the oldest iron sword (from the 10th century BCE) in the cave Mušja jama, which had come from the Aegean region. Limonite ore was plentiful, particularly in the Upper and Lower Carniola (Gorenjska and Dolenjska) regions.17

Most of the settlements from the Hallstatt period were situated on hills and minor elevations. They were encircled by sturdy defensive walls called hillforts. The fortifications used huge rocks for both frontal sides, with stone chippings and a mixture of clay poured between them. At the hillfort above Vir near Stična, excavations at the Cvinger site, whose perimeter measures 2.3 km, have revealed that houses stood close to the outer defenses, although a corridor allowed defenders free access to the wall. The houses were simple, rectangular wooden structures, erected either on piles driven into the ground, or else with upright supporting pillars placed on horizontal foundation beams (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.Iron Age house at Kučar near Podzemelj in the Lower Carniola (Dolenjska) region.

Most of the hillforts can be found in the Karst region as well as in Inner and Lower Carniola (Notranjska and Dolenjska). Those in Lower Carniola (Dolenjska) are the best researched, and it has been shown that the Urnfield inhabitants erected some unfortified settlements there, but life in them swiftly declined. In the 8th century BCE, new populations built larger settlements not only close to older ones, but also in completely new locations, usually reinforced by fortified stone walls. The Mirna valley was the most densely settled, while the main centers were Stična, Novo Mesto, Dolenjske Toplice, Veliki Vinji Vrh (Šmarjeta), Velike Malence, Libna, Podzemelj, Vače, and Magdalenska gora near Šmarje-Sap, in addition to many smaller settlements. The settlement at Molnik was situated in the periphery, already gravitating toward the Ljubljana Basin.18 In Inner Carniola (Notranjska), new hillforts were established at Šmihel below Nanos and Trnovo, but for unknown reasons they disappeared in the 7th century BCE. This is surprising, as life in the Posočje and Lower Carniola (Dolenjska) communities was flourishing precisely at that time.

Details

- Pages

- 622

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631910474

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631910481

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631910467

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21313

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (April)

- Keywords

- Catholisation Collaboration Feudalism Geschichte Humanism Independence process Occupation Post-Socialism Resistance Settlement of the Slavs Slowenien Socialism War

- Published

- Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, 2024. 622 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG