Ireland and Popular Culture

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Sylvie Mikowski: Introduction

- Darryl Jones: Dracula Goes to London

- Sandra Mayer: The Importance of Commemorating Literary Celebrity: Oscar Wilde and Contemporary Literary Memorial Culture

- Xavier Giudicelli: Dorian Gray in/and Popular Culture: Text, Image, Film

- Claire Poinsot: ‘Souls the like of ours/Are not precious to God as your soul is’: Elite, Popular and Folk Culture in William Butler Yeats’ Plays

- Adrienne Janus: Listening High and Low: Yeats, Joyce, Beckett and the Condition of Music in Modernist Irish Literature

- Yannick Bellenger-Morvan: C.S. Lewis: An Experiment in Popular Literature?

- Kevin Wallace: ‘Fintan O’Toole: Power Plays’ and the High Art/Low Art Discourse in the Narrative of Irish Theatre

- Chantal Dessaint-Payard: What Happened To Anna K? or the Dissemination of Cultures in Fox, Swallow, Scarecrow by Éilís Ní Dhuibhne

- Frédéric Armao: The Folklore of Spring in Ireland: A Dichotomy of Traditions

- Pádraic Frehan: National Self-Image: The Imagological Impact and Subsequent Contemporary Permeations of Celtic Mythology in Ireland’s School Literature from 1924

- Valérie Morisson: From Hinde to Hillen: Postcards and the Issue of Authenticity in Popular Culture

- Alexia Martin: The Carnsore Point Festival (1978–1981): Between Antinuclear Rally and Cultural Event

- Stephen Boyd: Surfing a Postnationalist Wave: The Role of Surfing in Irish Popular Culture

- Ruth Alexandra Moran: Please Say Something (2009): Digital Aesthetics and Popular Culture

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

← vi | vii → Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the persons and institutions without whose financial, scientific or personal support and encouragement the publication of this book would not have been possible:

–Centre Interdisciplinaire de Recherche sur les Langues et l’Elaboration de la Pensée (CIRLEP, EA 4299), Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne

–Région Champagne-Ardenne

–Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT), Dublin

–Prof. Thomas Nicklas, director of CIRLEP

–Dr Paula Gilligan, IADT

–Dr Maria Parsons, IADT

–Prof. Diane Negra (University College, Dublin)

–Prof. Darryl Jones (Trinity College, Dublin)

–Dr Eamon Maher, director of NCFIS, IT Tallaght← vii | viii →

Introduction

Even though it has for decades featured as a regular subject in academic curricula across universities in English-speaking countries, the study of popular culture has not yet been wholly recognized as a proper field of research in some European countries, particularly in France. This may seem all the more surprising as much of the theoretical background from which popular culture scholars have drawn their inspiration originates with French authors like Roland Barthes, Michel de Certeau or Michel Foucault. The suspicion surrounding the study of popular culture in France may stem from the long-held belief that the subject should not be taken seriously, a contention that also lies at the heart of the debate over the value and interest of popular culture which has been going on for centuries. Indeed, ever since Matthew Arnold defined culture as ‘the best that has been thought and said in the world’,1 claiming that only ‘high’ culture could save society from anarchy, some critics have argued that popular culture only tends to debase, corrupt and destroy all that is good and beautiful. Others have claimed on the other hand that ‘high’ culture is only an artificially-constructed territory jealously guarded by a privileged elite who creates and promotes aesthetic standards so as to better secure its superiority and domination over the lower, supposedly uncultivated and vulgar classes. Popular culture was often stigmatized under the derogatory name of ‘mass culture’, which in the eyes of cultural critics such as F.R. Leavis, was liable to undermine the ‘organic community’ and threaten the existence of a genuine ‘folk art’;2 according to ← 1 | 2 → the thinkers of the Frankfurt school such as Theodor Adorno, mass culture is imposed on people by a culture industry intent on creating and satisfying false needs.3 Through his theory of popular music, for instance, Adorno denounced the standardization and ‘pseudo-individualisation’ of popular culture, which according to him led people to recognize their difficulties, but made them accept the world as it is and stop wanting to change it.4 The Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci5 further problematized the opposition between mass and elite culture by introducing the notion of hegemony, a means by which he maintained the ruling classes exercise their power through the ‘spontaneous consent’ of the dominated groups. This consent is indeed spontaneous, insofar as the dominated classes can identify with the values the hegemonic culture conveys. However, hegemony is not ← 2 | 3 → acquired definitively, and culture thus becomes a site of conflict between the various components of society which in turn shape, influence and transform it. This dialectical movement was later conceptualized by Michel de Certeau through his ‘theory of practice’, arguing that the popular classes resist hegemonic culture by using it for their own purposes.6 John Fiske also explored this line of thought when he wrote that ‘popular culture is made by subordinated peoples in their own interests out of resources that also, contradictorily, serve the economic interests of the elite. Popular culture is made from within and below, not imposed from without or above as mass cultural theorists would have it.’7 Roland Barthes, in writing Mythologies,8 was the first French critic to take popular culture seriously, but mostly with a view to denouncing what he called the modern ‘myths’ of capitalist, consumerist society. Using what was at the time the fairly new science of semiology to analyse, among other things, items such as advertisements, cars, movie stars, newspaper reports or political slogans, Barthes was able to demonstrate that no object around us, nothing belonging to everyday life, is devoid of a significance. That significance was most of all, according to the French semiologist, a political one, aiming at forcing us to accept and obey a certain ideology or morality without our being even aware of it. The importance of the media, already noted by Barthes in 1957, grew in the second half of the twentieth century to form much of the essence of popular culture, to such an extent that philosophers and critics, in the wake of Jean-François Lyotard, Jean Baudrillard or Guy Debord, all pointed to the gradual substitution of reality by images of all kinds, a process described by Baudrillard as the production of ‘simulacra’9 and by Debord as ‘the society of the spectacle’.10 In this context, where the distinction between reality and ← 3 | 4 → its representations becomes blurred, and the image itself substitutes the message, the difference betwen ‘serious’ art and entertainment or leisure loses much of its significance, a confusion that contemporary artists play with in order to challenge the limitations of ‘good taste’ and also to convey a critique of consumerism. One of the best examples of this half-playful half-serious cultivated ambiguity between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art is the ‘pop art’ movement which appeared in the United Sates in the 1960s, with Andy Warhol parodying the visual language of advertising in his famous ‘Cans of Campbell Soup’ paintings, or Roy Lichtenstein reproducing the subjects and aesthetics of comic strips. To add to this potential interchangeability of artistic categories, some critics have also drawn attention to the variability in time of the concept of ‘high’ art, arguing that what was intially considered ‘popular’ is often at a later period annexed to the canon of elite culture: the case of American film noir, cherished today by the most enlightened film-lovers, whereas it originally aimed at a general audience, is often mentionned, as well as that of Shakespeare’s plays which for the most part were designed to please the popular element of the audience which crowded into the Globe Theatre. Pierre Bourdieu in his seminal study The Rules of Art,11 in which he analyses in detail the world of salons and art dealers in the nineteenth century, showed how the notions of ‘good taste’ and of the beautiful, are in fact artificially and historically constructed categories resulting from the combined efforts of various agents seeking to enhance their economic, social or political interests, all striving to foreground their ‘distinction’ as a class.

In other words, today’s thinkers tend to reject the platonic view of Beauty as being a transcendent category, denying as well the notion of an essence of culture, high or low, popular or not, which would exist outside history, social conflicts, or economic circumstances: hence the difficulty today of formulating an all-encompassing definition, which in turn explains why popular culture scholars tend to stick to some broad, general features, as is well captured in the following phrases: ‘the leisure ← 4 | 5 → activities which the working or middle classes of industrial society enjoy’;12 ‘as consisting of the arts, rituals, and events, myths and beliefs, and artefacts widely shared by a significant portion of a group of people at a specific time’;13 ‘the everyday world around us: the mass media, entertainments, diversions, heroes, icons, rituals, psychology, religion-our total life picture’;14 ‘Culture which is widely disseminated and consumed by large numbers of people’.15 As may be noticed, popular culture is thus considered by some to be dependent on a certain type of historical development, most often the industrial era, whereas in other cases it is deemed universal; in some cases the stress is laid on the notion of pleasure and enjoyment, in others, simply on the necessity that large numbers of people should be concerned by the consumption of the same cultural products. The difficulty of limiting the definition of popular culture within strict boundaries has been enhanced by the advent of the post-Gutenberg, digital age, which has created new media and completely transformed the modes of access to cultural products, enabling people to be not just the passive consumers, but also the producers, of culture, blurring even further the frontier between art and entertainment and between elite and popular cultures. Popular culture studies have had to adapt to these new developments by branching out into new sub-categories such as TV studies, celebrity studies, audience studies, etc, or by taking into account such new media as the world-wide web, computer-designed films, video installations, digitalized photography, electronic music, blogs, social networks. Another major evolution in the study of popular culture has been the increasingly essential fact of globalization which has deeply transformed our sense of a cultural heritage attached to a specific people or nation, which has been gradually replaced by the more contemporary concepts of multi-, trans- and inter-culturalism and hybridity, as contemplated by Edward Said: ‘all cultures are involved in one another; none is single ← 5 | 6 → and pure, all are hybrid, heterogeneous, extraordinarily differentiated and unmonolithic’. 16

Yet some nations have precisely aimed at claiming the singularity and originality of their culture, if only to resist the domination of hegemonic foreign powers: such is naturally the case of formerly colonized countries such as Ireland. The relationship between Ireland and popular culture is a complex one which moreover has evolved through time, and it exemplifies all the contradictions and ambiguities inherent in the notion of a ‘popular’ as opposed to an ‘elite’ culture. For instance, the fact that popular culture should often be associated with the industrial era is problematic insofar as Ireland remained mostly a rural country until it took a giant leap straight into the post-industrial era in the late twentieth century. The subjugation of the Irish nation to the territorial, political and economic interests of Britain, which lasted until 1921 and had prolonged effects on the nation’s psyche, meant that its native culture was relegated to the level of the subaltern, not just in reality, but also in the opinion of the ruling English and Anglo-Irish classes. Evidence of its alleged primitivism was for example found in its prevailingly oral tradition, which was opposed to the high degree of literacy prevailing in England; or in the store of legends, mythology and fairy-tales characterizing Irish culture, and which supposedly emphasized the contrast between a naive, primitive mindset, and the rationality of the English mind. As a result, Irish culture was more or less regarded with the same condescension as was popular culture in general, and it is perhaps no coincidence that the same Matthew Arnold who defended the superiority of high culture over Philistinism or Barbarism should also have been the one who wrote about the feminine – at a time when this necessarily implied inferior – essence of the Celtic soul.17 The continuous efforts of the colonizer to draw native Irish culture into the margins of ‘low’ or ‘popular’ culture were nevertheless countered by the rise of nationalism and its literary or artistic manifestations, as was especially the case during ← 6 | 7 → the two revivalist movements, the first taking place in the eighteenth century and the other, more famous one, at the end of the nineteenth. What is paradoxical is that in each case, the task of retrieving what remained of native Irish literature, art, music or achitecture from near extinction, was undertaken by members of the ruling Anglo-Irish Protestant ascendancy, for the simple reason that they were also at the time the only social class with access to education, culture, and to the means of circulating it through printing, publishing, collecting and curating, or of staging plays and concerts. That reclaiming and reconstruction of Irish ‘popular’ culture, or rather ‘folk’ culture – in the sense that the word designates the traditions, customs and beliefs handed down among a small community from generation to generation – was thus left in the hands of an elite who was not that eager to share its social privileges and political power with the ‘masses’. After this power was abolished with the advent of independence, efforts to promote the development of a culture that would be unique to the Irish people were undertaken by the new State, with the obligation imposed upon the citizens to practise genuine Irish sport, Irish dances, Irish music, and to keep away from non-Irish forms of entertainment such as English or American music, movies, magazines or even books, whose circulation was rendered very difficult by the very strict censorship laws introduced in the early years of independence. In that regard the ‘popular’ culture promoted by the new State and its ally the Catholic Church, could hardly be said to originate from the people themselves, even though the Irish had to be satisfied with it as the only source of affordable entertainment. Moreover, another paradox concerning Ireland and popular culture in the nationalist, post-independence period lies in the claim to the purity and singularity of Irish ‘folk’ or ‘popular’ culture, a notion used to forge and sustain a sense of Irish identity that would be first and foremost different from its British neighbour’s. Yet this emphasis on the homogeneity of Irish culture ran counter to the historical reality of English presence on Irish soil for over 400 years, and the hybridization of cultures that naturally followed; notwithstanding the effects of emigration, a major feature of Irish life ever since the Penal Laws of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but which reached a peak in the wake of the nineteenth-century Great Famine. As a consequence, and despite the State’s efforts to limit ← 7 | 8 → foreign influence through the control of cultural production, most Irish people were in contact with European – in most cases English – as well as American cultures well before the 1960s, when the nationalists in power finally had to acknowledge their error in privileging isolationism in all areas of life, from the economy to culture, and launched a programme of economic recovery mostly based on tax incentives offered to foreign companies so as to boost investment in Ireland. This voluntary opening-up of the country to international interests included the crucial decision to ‘sell’ Ireland as a tourist destination, an ominous turn in the development of Irish popular culture, which from then on was used as a marketing tool, as Michael Cronin and Barbara O’Connor underline in their pioneering collection of essays Tourism in Ireland: a Critical Analysis, published in 1993. Paradoxically, primitivism was again put forward as a key feature of Irish culture, but this time with a view to attracting foreign visitors yearning for a pristine, pre-industrial, pre-urban environment. At the same time as the succeeding Irish governments were embracing economic liberalism and praising Ireland’s entrance into modernity, they were also trying to sell the image of a country where time would have stopped in the pre-modern age, as Michael Cronin puts it: ‘Ireland could present itself in IDA advertising as a progressive, modern economy and at the same time, in tourism advertising, offer the image of a lackadaisical pre-modern culture, inhabited mainly by old men and (rustling) bicycles.’18 Such popular forms of entertainment as traditional music or dancing, food and drink, sport, festivals, were no longer presented as markers of identity meant to arouse nationalist feelings among Irish people themselves, but as tourist attractions. Irish writers, once closeted by some of the most restrictive laws on censorship in the Western world, were now enrolled in this widespread advertising campaign for Ireland, as was evidenced by the portraits of Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats, James Joyce, Brendan Behan, Samuel Beckett, and the like, being reproduced on calendars, tea-towels, table-mats, or even painted ← 8 | 9 → onto a wall in Dublin airport. A statue of James Joyce was erected in the city centre of Dublin, and quotations from Ulysses engraved on bronze plates were sealed into the city pavement for pedestrians to tread upon, whereas up until the 1970s it was almost impossible to find a copy of the book in a bookshop. Thanks to this intensive promotion, the Irish Tourist Board was hoping to attract not just wealthy, educated Western Europeans in search of ‘authenticity’ and rurality, in response to the rise of environmentalist, anti-consumerist trends in affluent countries – but also American tourists in search of their Irish roots, thus tightening the links between Irish and American popular cultures. Indeed the relationship between Ireland and the United States is reciprocical, implying the americanization of Irish culture on the one hand, and on the other the ‘special position’ of Irishness in American popular culture. The first derives more or less from the process of the americanization of popular culture at work all over the world, facilitated in Ireland by the constant flux of emigrants and re-migrants to and from the United States.

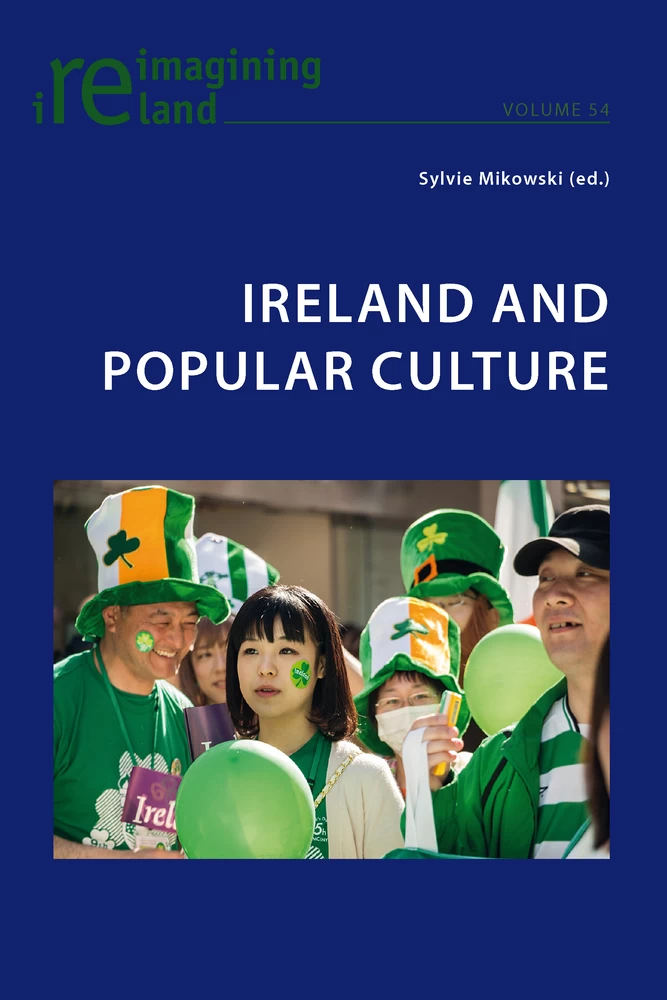

The other kind of relationship was analysed in a 2006 collection of essays edited by Diane Negra, The Irish in Us: Irishness, Performativity and Popular Culture,19 in which she stresses the rise of a real ‘Hibernophilia’ around the world and tries to understand its causes. She underlines how ‘Irishness has become a form of discursive currency, motivating and authenticating a variety of heritage narratives and commercial transactions’,20 and this especially in the United States. She argues that ‘Irishness has become particularly performative and mobile’, appearing in various contexts and under various shapes. Negra thus discovers what she terms ‘themes of Irishness’ in ‘television series, the genealogical practices of heritage-seekers, and performances of Irishness in celebrity culture’.21 She also notes that ‘Irishness has increasingly operated as a soundtrack as well as a narrative prototype’,22 listing Riverdance or the Titanic movie soundtrack, in ← 9 | 10 → addition to the global success of such bands as U2, The Cranberries, or The Corrs.23 Negra’s assumption about the causes of such a phenomenon is that ‘claiming Irishness often authorizes a location and celebration of whiteness in ways that would otherwise be problematic’.24

As a result, we may say that the phrase ‘Ireland and Popular culture’ encapsulates all the complexity and ambiguities regarding the exact nature of popular culture in Ireland today and in the past, its various manifestations, the image of Irish culture abroad, the way Irish culture accommodates the influence of foreign popular cultures, as it is the aim of each chapter of this volume to consider in turn. For instance, several chapters are devoted to some towering figures of Irish literature, who have all either used or been used by popular culture, and whose works also belong to the canon of ‘high’ literature in English, among them Bram Stoker, Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. What these writers have in common is that they have all in turn been claimed as part of a true native Irish heritage, despite, for some of them, their Anglo-Irish origin and the fact that they either spent most of their lives in England, or clearly rejected their motherland and claimed the universal significance of their writings. Indeed, recent Irish studies scholars have striven to highlight these artists’ Irishness, with a view to establishing and enriching a genuine Irish canon, and to foreground, if necessary, the existence of a ‘high’ native culture, as opposed to the hegemony of ‘high’ English literature. One of the most striking examples of this tendency was the publication between 1991 and 2002 of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature in three volumes, under the aegis of Seamus Deane; another example was the new readings of Bram Stoker’s Dracula as a kind of metaphor for Ireland’s troubled past, as in Joseph Valente’s Dracula’s Crypt: Bram Stoker, Irishness and the Question of Blood.25 Yet to limit culture, whether popular or not, to strict national boundaries is to ignore the circulation of people, ideas and commodities at ← 10 | 11 → a given period. In his chapter, Darryl Jones insists for instance on Stoker’s fascination with Victorian London, for as he puts it, London in 1897 was simply ‘the centre of the world’. Jones’s reading links details from the novel to precise historical information in relation to the everyday life of a great city at the turn of the nineteenth century, with its modern means of transportation, its real estate market, its clubs and societies, its banks and shops and restaurants, its various ethnic communities, its political factions, its hospitals and cemeteries, its sanitation problems. He also draws a parallel with other works belonging to the same genre, or rather mixture of genres, which were highly popular at the time of its publication, such as H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, Arthur Conan Doyle’s Adventures of Sherlock Holmes or Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White. The hybridity of the novel, to which some assign a true Irish identity, but is firmly set against an English background, which displays the same features as some of the most popular genres of its period, but today belongs to the canon of high literature, is thus exemplary of the multifacetedness of popular culture.

Oscar Wilde is another of those Irish writers who was first claimed on both sides of the Irish Sea and who finally rose to the status of global celebrity. This precursor of self-advertising, who fashioned his image so as to attract the media of his time, has gradually been metamorphosed into a contemporary myth, as Barthes would have it. A refined aesthete who placed the quest for beauty above everything, a scholar whose works were inspired by the most intimate knowledge of elite culture, Wilde also seduced the largest audiences of his times in London theatres thanks to light comedies with a serious intent, drawing our attention to the relativity of ‘the importance of being earnest’. Far from the ‘death of the author’ proclaimed by Michel Foucault and formalist critics in general, the strange case of Oscar Wilde reveals that the writer with a tragic fate has not been just rehabilitated, but as it were resurrected, as Sandra Mayer argues in her chapter. The need to commemorate Wilde, she posits, stems from the contemporary ‘mourning urge’, from the entanglement of life and work so typical of contemporary taste, from the sexual scandal which provides us with an impression of intimacy with the ‘real’ Oscar, but mostly from the protean identity that the writer has come to embody to the eyes of our contemporaries, and his ‘potential of being everything to everyone’. ← 11 | 12 → What’s more, in the same way that Wilde’s life had the potential for multiple reincarnations, his works have been subjected to multiple readings, re-writings, transpositions, sequels and prequels. In line with this point, Xavier Giudicelli examines how The Picture of Dorian Gray was in particular subjected to transemiotic adaptations. Giudicelli thus successively underlines the ‘spectral presence’ of Wilde in Todd Haynes’s 1998 film Velvet Goldmine, the decontextualization and recontextualization of The Picture of Dorian Gray in Will Self’s 2002 novel Dorian, and the adaptation of The Picture into various graphic novels. The novel, although deeply influenced by Hellenism and preceded by a preface in which Wilde asserts art’s superiority over life, has thus evidenced a potential, not just to endure through time, but to cross and to blur the lines between high and popular culture.

This plasticity is more problematic in the case of William B. Yeats, even though he was intent on addressing the largest audience possible, provided they were ready to listen to the odd language he was using. Indeed Yeats’ notion of popular culture stopped at the point of ‘folk’ culture, repudiating as he did the effects of industrialization often associated with the rise of popular or mass culture. Several of his plays use characters from tales and legends, such as Cathleen ni Houlihan, which, as Claire Poinsot reminds us in her chapter, was an immediate success, but perhaps mainly for political reasons, rather than because it appealed to the taste of a large audience; besides, some of Yeats’ other plays were more daring and experimental, such as those based on Noh theatre; hence the paradox that what was initially meant for a large audience was in fact accessible only to a small elite. This fine tuning of literary language to the taste and habits of a mass audience is also the subject of Adrienne Janus’s chapter. Drawing on what she calls the ‘polarization of music’ in Ireland, namely the tension created by the nationalist Ireland’s tradition of privileging native Irish ‘folk’ or ‘popular’ music as opposed to European art music, Janus contends that the same opposition between ‘high’ and ‘low’ listening can be recognized in the works of Yeats, Joyce and Beckett. Each in his own way attempted to ‘fuse modes of high and low listening’. Yeats mixed the ‘simple emotions of popular ballads’ with the most experimental forms of language, such as in his poems written for the psaltery, but he moved on in his later poems to the creation of the most modern acoustic effects. Joyce also attempted ← 12 | 13 → to ‘fuse “high” and “low”, reading and listening, written composition and embodied performance’, such as in the Sirens episode of Ulysses. As for Beckett, through his use of modern mass media, he managed in his radio plays not just to overcome the polarization of high/low music, but also to dissolve all acoustic presences into ‘one common denominator which can be identified neither as words or music, high or low culture’.

This attempt to overcome boundaries between high and low can also be perceived in the works of C.S. Lewis, although for entirely different reasons, as Yannick Bellenger-Morvan explains in her chapter. This paragon of highbrow culture, an Oxford then a Cambridge don, meant to carry through ‘an experiment in popular fiction’ with his Narnia Chronicles, which became an all-time international children’s literature best-seller and more recently a Hollywood blockbuster. Bellenger-Morvan reports the dispute between Lewis and his Cambridge peers F.R. and Queanie Leavis, who despised popular literature, and to whom Lewis proposed the idea that highbrow culture should be made accessible to everybody. His works were therefore meant to offer ‘an access to books his readers would not have necessarily turned to or enjoyed’. Lewis also refuted the modernists’ elitist cultivation of form over meaning. This worship of avant-gardism and of art for art’s sake is not a thing of the past, Kevin Wallace tells us in a chapter that is critical of Fintan O’Toole’s RTÉ documentary film, ‘Fintan O’Toole: Power Plays’. In it, O’Toole, the Irish Times columnist, who has more or less been raised to the status of national arbiter of good taste in contemporary Irish culture, scrutinized contemporary Irish playwrights’ alleged inability or reluctance to register the current transformations in Irish society, especially after the Celtic Tiger era. Yet Wallace argues that this accusation fails in its turn to register the existence of ‘Fringe Theatre’ productions taking place outside the celebrated Abbey or Gate Theatres; by ignoring these, and privileging the established traditions embodied by the Abbey and the Gate, O’Toole re-introduces a distinction between elite and popular, high and low forms of art. As a matter of fact, each era finds its own ways of producing signs of ‘distinction’, and what may have been first regarded as subversive and revolutionary – as was certainly the case of the Abbey when Yeats and his friends created it – can later become integrated into the hegemonic culture and constitute the canon, excluding more marginal forms of expression in its turn.

← 13 | 14 → The variability of the reception of ‘high’ and ‘low’ art is a concern shared by folklore specialist, short story writer and novelist Éilís Ní Dhuibhne. A keen observer of the growing submission of Irish art and artists to the demands of the economy, and of the commodification of Irish culture, she has provided with her 2007 novel Fox, Swallow, Scarecrow not only a scathing satire of Celtic Tiger consumerist frenzy, but also a deep reflection on the complex status of the ‘high/low’ culture divide today. Chantal Dessaint-Payard shows in her chapter that as a conscious re-writing of the all-time classic Anna Karenina, Fox, Swallow, Scarecrow questions the current possibility of producing a literature that would be exempt from parody, playfulness, allusions and hybridity. The notions of originality, authenticity and creativity have indeed all been swept away by the effects of ‘the postmodern condition’ but also by globalization, the two combining to abolish all frontiers between native and foreign, near and distant, old and new, elite and popular. Today everybody knows about Anna Karenina: even if they haven’t read the book, they have come across allusions to it through TV, cinema, music, advertising or video games, as well as by millions of other references, which make up the foundations of contemporary culture. To this ‘dissemination’ of culture, which can seem both deceptive and superficial, Ní Dhuibhne opposes the resistance afforded by folklore, as in Fox, Swallow, Scarecrow the supernatural events which bring the story to an end also bring back the main protagonist to reality, restoring her sense of her true self and of true art, as if only traditional popular culture were able to reach a ‘mythic and universal dimension’. True, the relationship between folk and mass culture has always been a complex one in Ireland. Even though folklore is supposed to emanate from the people and be spontaneous, in Ireland it has been consciously used by opinion-makers or by governments, either as a marker of national identity or, in more recent times, to market Ireland as one of the last European outposts of authenticity, and the Irish as one of the last surviving organic communities in the Western world.

That there is an authentic folkloric tradition in Ireland cannot be denied, as Frédéric Armao’s description of the traditional Celtic festivals of Bealtaine, Samhain, Imbolc and Lughnasa reminds us. But the transmission of ancient beliefs, customs and myths was also actively encouraged initially by nationalist movements in the nineteenth century, then by the Irish ← 14 | 15 → state. The role of education in that matter is evidenced by Pádraig Frehan’s research on the teaching of Celtic mythology in Irish school literature. Already transcribed and assimilated by the writers of the Celtic Revival, the stories of Fionn and his warriors, of Cuchulainn, Oisin and Niamh, of the Children of Lir, were published in the middle of the twentieth century in book series specifically addressed to young readers, accompanied by illustrations and iconography, so that the ‘mythology genre […] was embedded in the minds of the young population’. As Frehan puts it, ‘the inclusion of such images could influence the young readers’ minds in imagining and developing the historical and cultural heritage of their country’. Irish mythology has indeed become so embedded in the country’s self-image and in the image that the Irish wish to project of themselves abroad, that it keeps re-surfacing in the most unexpected areas of cultural, entertainment or leisure activities, as Stephen Boyd shows in his chapter on Irish surfing, a fairly recent sport which has benefited from the development of the leisure economy fuelled by the Celtic Tiger. Yet Boyd contends that even though Irish surfing media – films, magazines, advertisements – have appropriated iconography and signifiers from Celtic mythology – calling a famous wave ‘Aileens’ or using Celtic designs on shop-fronts and posters – they have done so by emptying those signs of any political, nationalist connotation, so that surfing has in its own way contributed to the construction of a contemporary ‘post-nationalist identity in Ireland’. This playful recycling and quiet subversion of myths and images previously forged and promoted to support and boost a sense of national identity is also at stake in Valérie Morisson’s chapter on John Hinde’s postcards and their ‘customization’ and re-interpretation by contemporary visual artist Seán Hillen. Hinde’s postcards raise the issue of authenticity in popular cuture in the most literal sense: indeed, even though his pictures were supposed to represent ‘real Ireland’, the photographer resorted to all sorts of artificial devices to make them, such as dressing his characters in traditional costumes, taking hours to compose each photograph, colouring them in bright, gaudy, unnatural colours, all meant ‘to beguile tourists into undertaking a journey into the absolute fake’. The fakeness of Hinde’s postcards was subsequently undermined, subverted and parodied by Seán Hillen’s Irelantis and Searching for Evidence series, thus providing an ‘ironic rereading of established versions ← 15 | 16 → of authentic Irishness’. But Irish folklore today is not necessarily an object of parody through emphasis upon its kitschiness; it has retained some of its potential subversive power. Traditional Irish folk music, for instance, can still be the vehicle of precise political claims, as Alexia Martin shows in her chapter on the antinuclear rallies organized at the end of the 1970s, in which singers and musicians played an essential role in ‘undermining the plans for an Irish nuclear plant’. Traditional popular music was used here to convey the sense that Ireland was to keep its native attachment to nature, perceived to be innate to Celtic spirituality. Like surfing, the environmental movement thus empties traditional Irish popular culture of its nationalist connotations to adapt it to the contemporary longing for a return to closeness with nature.

Details

- Pages

- VI, 249

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034317177

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035304770

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035394702

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035394719

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0477-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (March)

- Keywords

- mythology folklore sport theatre national identity

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2014. 249 pp., 6 coloured ill., 1 b/w ill., 5 fig., 1 table

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG