Defining the Indefinable: Delimiting Hindi

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Defining Hindi: An Introductory Overview

- Reference

- Hindi Revisited: Language and Language Policies in India in Perspective

- Reference

- Traces of Sacredness in Imaginings of Hindi

- 1. Sacred Languages and the Case of Sanskrit

- 2. Sacred Texts in “Hindi”

- 3. Hindi as Heir to Sanskrit and the Nagari Linkage

- 4. Hindutva and Hindi

- 5. Popular Misunderstandings

- 6. Conclusion

- Reference

- Depoliticising Hindi in India

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Depoliticising Hindi in the South

- 3. Depoliticising Hindi in the North Indian Hindi Belt

- 4. Conclusion

- Reference

- Hindi as a Contact Language of Northeast India

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1. The Official Strength of Hindi Speakers

- 1.2. Varieties of Hindi

- 2. Hindi Used in Arunachal Pradesh

- 2.1. The Structure of Arunachalese Hindi

- 2.1.1. Formation of the Plural

- 2.1.2. Lack of Agreement

- 2.1.3. Absence of Oblique Marking

- 2.1.4. Lexicon: Some Peculiarities

- 2.1.5. Innovations

- 3. Hindi Used in Meghalaya

- 3.1. Degree of Competence in Meghalaya Hindi

- 3.2. Structure of Meghalaya Hindi

- 4. Common features of Arunachalese Hindi and Meghalaya Hindi

- 4.1. Vulnerability of Adoption

- 4.2. Particle -vālā

- 4.3. Use of Modal sak as a Main Verb

- 4.4. Adjectives and Nouns Can Occupy the Predicate Slot

- 5. Conclusion

- Reference

- Linguistic Relationships: Bhojpuri and Standard Hindi. A View from the Western Hemisphere

- Introduction

- Historical Relationship between Bhojpuri and ‘Hindi’

- A View from the Western Hemisphere

- Nomenclature

- Interaction between Various Speech Forms

- Relationship between Guyanese Bhojpuri and Standard Hindi

- Rise of the Intermediate Variety

- Reference

- Filmī Zubān. The Language of Hindi Cinema

- 1. Hindi in Urdu, Urdu in Hindi

- 2. Gangā-Jamunī Tahẕīb

- 3. Avadh to Bombay, Lahore to Bombay

- 3.1. Parsi Theatre

- 3.2. Urdu Writers

- 3.3. Punjabi Migration

- 4. Iśḵ, Farz, Daulat and Tasavvuf

- 5. Filmī Dialoguebaazi

- 6. Ġazal, Šācirī and the Hindi Film Romance

- 7. Conclusion

- Reference

- Hindi/Urdu/Hindustani in the Metropolises: Visual (and Other) Impressions

- 1. The Fate of Urdu in Independent India

- 2. Languages/Scripts in Public Spaces

- 2.1. Delhi

- 2.2. Mumbai

- 2.3. Hyderabad

- 3. Linguistic Shifts (Hindi/Urdu/Hindustani)—the Example of Delhi

- Reference

- A Mixed Language? Hinglish and Business Hindi

- 1. Hindi and Mixing, or, How Mixed Is Hindi?

- 2. Business Hindi: A Mixed Variety of a Nationwide Language?

- 2.1. Official Regulations on Business Hindi

- 2.2. Use of Business Hindi in Official Documents

- 2.3. Business Hindi—Oral Communication and Presence in the Public Domain

- 3. Conclusion

- Reference

- List of Contributors

The genesis of this volume lies ultimately in the longstanding academic cooperation on contemporary South Asian languages, particularly Hindi/Urdu, between the Südasien-Seminar of the Orientalisches Institut of the Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) and the Instytut Orientalistyczny of the Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie (JU). The cooperation includes delving into the issue of what “Hindi” does and does not encompass.

Building on ideas thus developed, the matter of delimiting “Hindi” was taken up in a workshop in Halle (Germany) on the premises of the MLU, but in the context of the official university partnership between the MLU and the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi (JNU). The workshop, on Where Linguistics and Politics Meet: Defining Hindi, was held on November 21–22, 2008; it was organised by Rahul Peter Das and Anvita Abbi, and funded by the MLU and the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. The participants were Anvita Abbi (JNU), Rahul Peter Das and Felix Otter (both MLU), Heinz Werner Wessler (Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn), Christina Oesterheld and Hans Harder (both Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg), Surendra K. Gambhir (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) and Anil Biltoo (University of London).

Though, unfortunately, the attendance of JU participants from Cracow (Poland) could not be realised at the time, it was decided subsequently that the workshop would be followed up cooperatively, not only, but particularly through the publication of a volume on the subject, to be prepared at the JU. The papers presented at the Halle workshop were, of course, to constitute an integral and major part of this volume.

To this end, the workshop presentations have been reworked by the participants, with the exception of three which could not be thus prepared, namely one (on Indian government policy on Hindi and the three language formula) of Anvita Abbi’s two presentations, and the presentations of Felix Otter (on non-Indian government policies in South Asia, particularly Nepal, regarding Hindi and its “dialects”) and Anil Biltoo (on “Hindi” in Indian Ocean states). The paper ← 7 | 8 → of Anvita Abbi published here has been co-authored by Maansi Sharma (JNU). Further, three additional papers have been solicited and most kindly submitted for inclusion, namely one by Agnieszka Kuczkiewicz-Fraś and Dagmara Gil (both JU), and one each by Anjali Gera Roy (Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur) and Selma K. Sonntag (Humboldt State University, Arcata CA).

Sincere thanks are due to all the contributors for their immense patience and forbearance with the tortuous development of this volume.

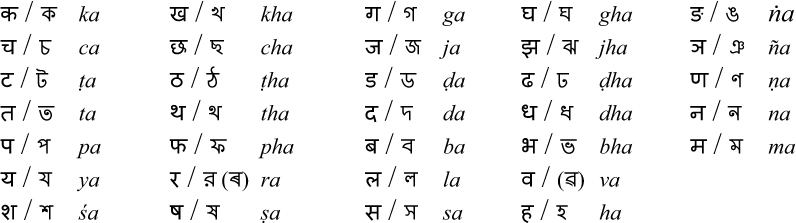

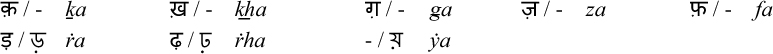

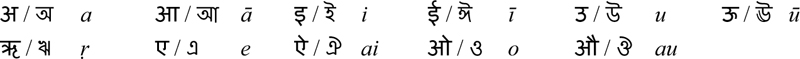

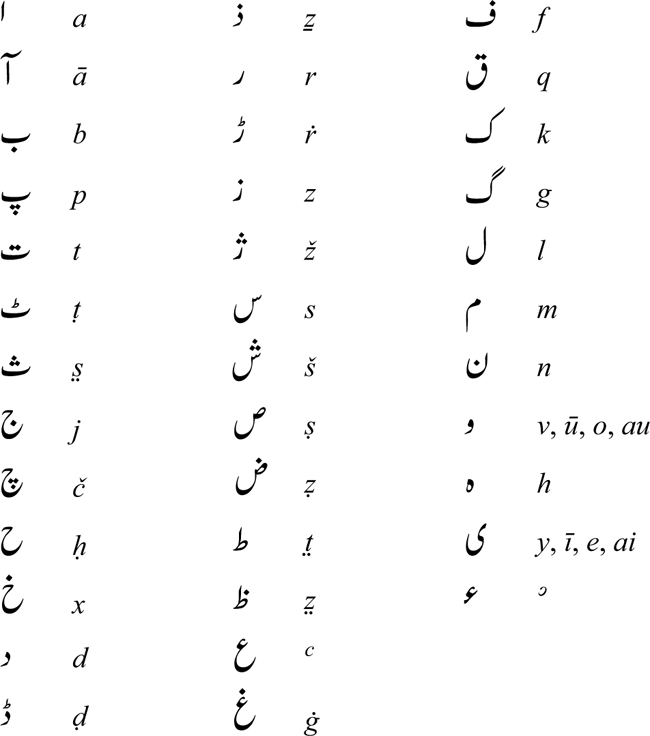

The Roman transliteration used in the volume follows the systems developed for the Nagari/Bengali script and the modified Arabic script respectively. Single words, phrases, quotations and titles coming from Hindi, Bengali, and Urdu have been transliterated according to the rules given in the following tables. The systems adopted attempt to be exact, so that the reader should be able to reconstruct the original spelling of transliterated words or texts. In the English main text of the book, the simplified phonemic transcription applies to foreign words and phrases that have become common in English—like geographical and proper names, names of languages (e.g. Punjabi, Assamese), cultural or religious terms (e.g. Sufi, Guru), etc.

Cyrillic has been Romanised according to the British standard used by the Oxford University Press, which can be found, e.g., in: The Oxford Style Manual, ed. by Robert M. Ritter, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 350.

Nagari and Bengali (Assamese)

Consonants:

Modifications: ← 8 | 9 →

Vowels:

* a which is not pronounced is indicated by  , except at the end of a word

, except at the end of a word

*  is indicated by

is indicated by

* word-initial  is indicated by ä

is indicated by ä

anusvāra  ṃ visarga : ḥ anunāsika (candrabindu)

ṃ visarga : ḥ anunāsika (candrabindu)  ṁ virāma

ṁ virāma

Urdu script

*  is transliterated as e and

is transliterated as e and  is transliterated as ṅ.

is transliterated as ṅ.

← 9 | 10 → ← 10 | 11 →

Defining Hindi: An Introductory Overview

At that time [after the Revolution of 1789] the longstanding and previously unremarkable existence within the French polity of substantial subcommunities who neither spoke nor understood French came to be viewed as unacceptable. The unity of the new revolutionary state was henceforth to be expressed via a common language, replacing the linguistic heterogeneity that in the revolutionary view had served the purposes of a discredited monarchy by preventing various segments of the country’s population from making common cause with one another. The Alsatians, the Basques, the Bretons, and the Occitanians would come to feel their national unity and would express it, according to revolutionary tenets, by adopting the use of the French language. Certain characteristically European ideological positions were given expression in the implementation of this policy. A single language variety associated with people of high social position (the king and his court, in this case) was accorded fixed form and unique authority through standardization, and a monopoly of legitimacy and prestige was conferred on that single form. In the resultant linguistic hierarchy, the unstandardized language varieties of politically and socially subordinate peoples within the state underwent a parallel attitudinal subordination and were subjected to what has been termed an “ideology of contempt” (…) (DORIAN 2006: 441)

1. Both the importance of language in India and the potential for conflicts based on language are very evident from the fact that many of the Indian states have been created on the basis of language, and from the developments which led to their creation. In keeping with this, a Bengali publication over twenty years ago opined (BHAṬṬĀCĀRYA 1990: 21; translated from the original Bengali):

Just as in religious matters nowadays morning’s rumour, becoming noon’s riot, turns to heaps of corpses at night, so in the field of language too has that calamitous danger been prevalent. Still, religion has one advantage compared to language in this country. For, however many riots there may be, this is nevertheless not a country of religious diversity. The proportion of only four religions is over 1 percent here. And the proportional majority of the Hindus is seven times more than that of the second-placed. Hindus are here 82.6 parts, Muslims 11.4, Christians 2.4, Sikhs 2 (the source of the data is the 1971 census), but there are fifteen languages over 1 percent. The diversity of India within which we seek unity is mainly linguistic and cultural diversity. According to Grierson’s calculations there are 723 languages and dialects in ← 11 | 12 → this country. (…) Discussing language policy in an essay twenty-eight years ago, Annada Shankar Ray1 said, “A multilingual country will become many states,” “If India disintegrates, it will be on the very issue of language.”2

The numerical data given do make it theoretically probable that any given conflict will be more likely linguistically motivated than religiously. Whether the history of conflicts in independent India actually substantiates this needs looking into, but that language has long been regarded as problematic is borne out by the statement of a scholar visiting India over forty years ago (SASAKI 1971: 93):

The problem of language is really one of the most severe headaches in modern India. Everywhere I visited, whether universities or government offices, I found officers, teachers and traders who were complaining of the complexity of language and criticizing the final decision of the Government to establish one official language. According to them, the question of official languages (…) was decided at a time when the wounds of the Indo-Pakistan partition had not yet healed and the communal disturbances following it had created conditions in which sober thinking was impossible.

Here particularly the issues of “one official language” and “official languages” are highlighted as problematic.3 Indeed, this is described as a major problem even today by the succinct enunciation of a recent study (ANEESH 2010: 93):

In twentieth-century India, language is spoken of in terms of a crisis. It emerges as a “problem.” Debates on language attain a centrality in cultural concerns, previously unseen in history. (…) The question of language chiefly relates with three problems: first, “a” language was required to take birth in order to fulfill growing nationalist aspirations; second, this future language was to carry out an impossible task of binding an emerging nation together, of taming the cultural profusion of more than 100 languages and a whole spectrum of religious practices; and third, the above tasks were to be performed without coercing the already existing linguistic subnationalisms informed in turn by the cognitive frame of total closure.

2. As the above also makes clear, language as such is rarely at the base of language related problems; rather, it is the factors associated with language which cause these. One of these is clearly the issue of group identity. Of course, group ← 12 | 13 → identity need not depend upon language;4 not only have numerous political entities since the dawn of known history been multilingual,5 and continue to be so, but this is also true of smaller entities such as families.6 Indeed, in one classic study, that of the Lue of Northern Thailand, the researcher found that criteria such as language, culture, polity, society etc. were no dependable identificatory factors, and concluded (MOERMAN 1965: 1222): “Someone is a Lue by virtue of believing and calling himself Lue and of acting in ways that validate his Lueness.”7

Similarly, there are South Asian scholars who hold that, traditionally, in the heterogeneous South Asian setting belonging to a particular language group was, and mostly still is, of little importance, of primary import being, rather, the sense of being part of an areal organic unity, for which Lachman M. Khubchandani utilises the term “sociolinguistic area,”8 explicating this through the Sanskrit term kṣetra-, which he explains in detail as (KHUBCHANDANI 1992: 99–100)

a traditional Indian concept focusing on the patterns of organic unity emerging in an area in the midst of a wide spectrum of linguistic and cultural variation in everyday life. (…) This concept of kshetra is markedly different from the modern western model of region defined as ‘a cohesive and homogenous area’ created by arbitrary selection of transient features such as religion, language, history. During the Independence struggle, it was rather naively assumed that the states based on the principle of linguistic homogeneity would provide a common bond among citizens and a convenient measure for better administration. This assumption goes contrary to the sociolinguistic realities signified by kshetras as a characteristic of Indian heritage.9 ← 13 | 14 →

Nevertheless, it would be a severe negation of reality to say that language plays no role at all in identity formation; indeed, language awareness has been called an elementary component of the search for identity (HAARMANN 1999: 91–92; translated from the original German):

If language awareness is an elementary component of the establishment of identity, then all humans in all cultures possess an awareness of the significance of their language or—inasmuch as several languages are involved—of their functional differentiation for the interaction in the cultural environment familiar to them. Language awareness is a timeless phenomenon and no “invention” of enlightenment thought of the 18th century, when the attention of the Europeans was drawn towards recognising and valuing national singularities such as the mother tongue.10

As Jaswant Singh points out (SINGH, J. 2012: 31), Jamaluddin (al-)Afghani, before he turned to pan-Islamism, in the latter half of the nineteenth century stressed the need for having a nationality, holding that this intrinsically depends upon language, the unity of language being more durable than that of religion.

3. This does not, of course, imply that such language awareness must come to the fore as a dominant factor in all contexts, as the examples in § 2 show; after all, different sorts of identity can be at work at different levels.11 “All civ ← 14 | 15 → ilizations have language but societies do not put this universal implement to the same use” (KAVIRAJ 2010: 127). This gives rise to a complex situation, which a researcher, writing on German nationalism, points out, combined with a warning not to project later developments backwards in time (SCHNEIDMÜLLER 1995: 85; translated from the original German):

Details

- Pages

- 208

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631647745

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653035667

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653988741

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653988758

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-03566-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (September)

- Keywords

- Diaspora Sprachenpolitik Verkehrssprache Mehrsprachigkeit

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 208 pp., 25 b/w fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG