Teach For America Counter-Narratives

Alumni Speak Up and Speak Out

Summary

This book – the first of its kind – provides alumni of TFA with the opportunity to share their insight on the organization. And perhaps more importantly, this collection of counter-narratives serves as a testament that many of the claims made by TFA are, in fact, myths that ultimately hurt teachers and students. No longer will alumni voices be silenced in the name of corporate and neoliberal education reform.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Praise for Teach For America Counter-Narratives

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Section I: TFA’s Recruitment, Training, and Support Structure

- Chapter One: The TFA Bait and Switch: From “You’ll Be Making a Difference” to “You’re Making Excuses”

- Chapter Two: The Blip on the Resume or the Seed of Social Justice?: The Eight-Year Impact of Eight Months with Teach For America

- Chapter Three: Productive Mistakes: Teacher Mentorship and Teach For America

- Chapter Four: Ignoring the Ghost of Horace Mann: A Reflective Critique of Teach For America’s Solipsistic Pedagogy

- Chapter Five: What Is an Excellent Education? The Role of Theory in Teach For America

- Chapter Six: Teach for Ambivalence, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love to Teach

- Chapter Seven: Teach For America, Neoliberalism, and the Effect on Special Education

- Section II: TFA’s Approach to Diversity

- Chapter Eight: Dysconscious Racism, Class Privilege, and TFA

- Chapter Nine: Perpetuating, Committing, and Cultivating Racism: The Real Movement Behind TFA

- Chapter Ten: Teach For (Whose?) America

- Chapter Eleven: Elite by Association, but at What Expense? Teach For America, Colonizing Perspectives, and a Personal Evolution

- Chapter Twelve: “I Always Finish Everything”: The Challenge of Living Up to My TFA Commitment

- Chapter Thirteen: The Gaps Between You and Me: Being Gay in TFA

- Section III: TFA’s Approach to Criticism and Critics

- Chapter Fourteen: Good Intentions Gone Bad: Teach For America’s Transformation from a Small, Humble Nonprofit into an Elitist Corporate Behemoth

- Chapter Fifteen: “I Confess, I Am a TFA Supporter. But…”

- Chapter Sixteen: From 106th to 41st, One Chicagoan’s Experience with Teach For America and Chicago Public Schools

- Chapter Seventeen: Can We Change? Reflections on TFA’s Ongoing Internal Criticism

- Chapter Eighteen: Beyond Dupes, Disciples, and Dilettantes: Ideological Struggles of TFA Corps Members

- Chapter Nineteen: Voices of Revitalization: Challenging the Singularity of Teach For America’s “Echo Chamber”

- Chapter Twenty: The Grandfather of Alumni TFA Critics

- Index

- Series Index

TEACH FOR AMERICA: HISTORICAL AND CURRENT CONTEXT

The idea for Teach For America (TFA) was originally proposed in Wendy Kopp’s (1989) senior thesis, An Argument and Plan for the Creation of the Teacher Corps, presented to the faculty of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University. In that document, Kopp outlined the need for alternatively certified teachers to ameliorate the national teacher shortage of the late 1980s, while putting forward an argument for “smarter” teachers in the profession—those who Kopp labeled the “best and brightest.” From its inception, TFA has relied heavily on ties to corporate and venture philanthropic organizations for its funding (deMarrais, 2012; deMarrais, Lewis, & Wenner, 2011) as well as extensive federal funding.

And while the first 20 years of TFA were billed as working toward a viable solution for addressing teacher shortages, the organization has slowly transformed into acting on Kopp’s second assumption, that traditionally trained teachers are not as qualified or intelligent as they should be; her cadre of Ivy League, predominantly White, and affluent corps members are innately better suited to become teachers because education majors have low SAT scores (Goldstein, 2014). This change is evident in the organization’s recent shift away from rhetoric about teacher shortages to an argument that the 145 hours of training corps members receive ← 1 | 2 → during TFA’s Summer Institute—only 18 hours of which are “teaching” hours (Brewer, 2014)—is superior to the traditional 4-year college degree and student teaching semester.

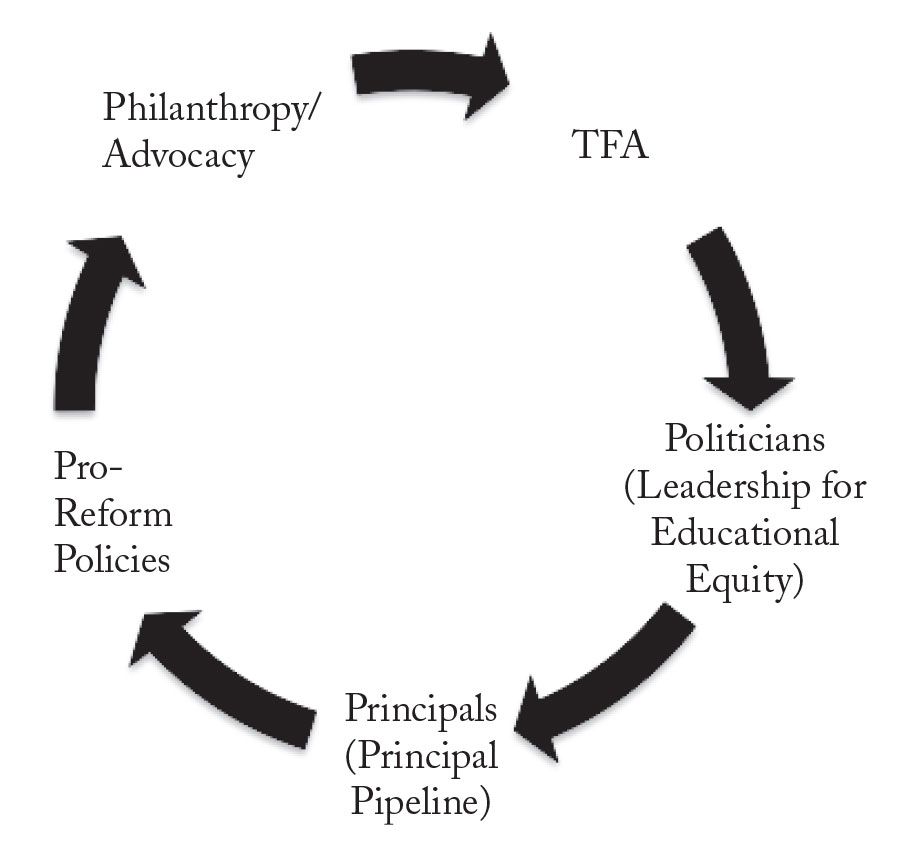

A more recent shift in TFA’s strategy has been exemplified by its push to create “educational leaders” by way of principals and elected policy officials (e.g., school board members, state representatives, etc.). The organization has moved from its early focus on teacher shortages toward an effort to influence educational policies and practices. To facilitate these efforts, TFA created its 501(c)4 spin-off organization, Leadership for Educational Equity (LEE), which promotes and supports the political campaigns of TFA alumni (Cersonsky, 2012; Simon, 2013) and assists candidates in attracting significant financial contributions (Magan, 2014). What is troubling about TFA’s involvement in propping up TFA candidates, all of whom are former TFA corps members, is that those individuals largely support pro-reform policies that TFA supports (Jacobsen & Wilder Linkow, 2014). In addition to the organization’s goal of installing alumni into policy positions, TFA has also focused on installing alumni as school principals. Accordingly, with TFA’s “Principal Pipeline,” alumni with just 2 to 3 years teaching experience are sent to a partnering university (Columbia University was the first) for coursework in administration, and the end result is a job back in a TFA region as a principal—ultimately, with hiring power to expand the number of TFA teachers. TFA’s organizational focus has strayed from seemingly humble and benign aspirations of contributing to the profession to seeking outright control of the profession by way of TFA’s circle of influence (see Figure 1).

In addition to its U.S.-based programs, TFA has expanded its efforts to export its brand of pedagogical and education reform internationally by way of Teach For All (TFAll). Launched at the Clinton Global Initiative in 2007 (Dillon, 2011), TFAll has now expanded into 34 countries in addition to the United States (Teach For All, n.d.). ← 2 | 3 →

Figure 1. TFA Circle of Influence.

AIM OF THIS BOOK

TFA has been, without doubt, very successful in growing its brand of alternative teacher certification since its inception in 1990. And while TFA did not invent behavioristic classroom management styles or test-focused pedagogy, part of TFA’s success—particularly in garnering millions of dollars from private venture philanthropists—is grounded in its adoption of such classroom practices. TFA is not the only alternative certification program that exists, but it certainly garners the bulk of attention, because

the debate TFA opened up about teacher preparation and quality teaching, while often rancorous, has been deeper and more evidence-based than any the nation has had since the inception of common schooling in the nineteenth century. In part, this is because so many TFA alumni have written frankly about their experiences and have had the connections to amplify their critiques and defenses of the program through magazine articles, books, and op-eds. (Goldstein, 2014, p. 195)

And, although the debate surrounding TFA has become rancorous in recent years through anti-TFA events (Black, 2013), the trending Twitter hashtag #resistTFA (Strauss, 2014a), calls by student activist organizations for universities to break ties with TFA (Strauss, 2014b), and an increase in academic critique (Kovacs & deMarrais, 2013), TFA has historically enjoyed a largely positive image in the media (Brewer & Wallis, in press). Yet, TFA has actively responded to this growing tide of criticism in an effort to salvage its reputation. The article “This Is What ← 3 | 4 → Happens When You Criticize Teach For America” (Joseph, 2014) was published in The Nation just as our authors were submitting their final chapters for this project. That article not only highlights the uniquely oppressive nature of TFA’s public relations team when dealing with dissent, it also illustrates the realities that alumni face when seeking venues for critique of the organization.

The inspiration for this book sprang from an increase in the number of emails that Jameson Brewer (a Metro-Atlanta corps member from 2010–2012 and a 2011 Atlanta Institute school operations manager) received from active TFA corps members, recent alumni, and those who recently had quit TFA prior to the end of their 2-year teaching commitments. Many of the authors of those emails expressed their thanks to Brewer for putting into words (Brewer, 2012, 2013) the feelings that they felt on a daily basis, and also their utter dismay at their experiences with TFA. This project has, of course, had the usual obstacles associated with organizing chapters into a cohesive volume. However, the process was made more problematic by the nature of the relationship TFA has with its dissenters.

During the course of our active call for chapter proposals, we received numerous emails and phone calls from corps members and alumni interested in the opportunity to share their stories, perspectives, and insights. What was surprising was the percentage of those individuals who asked if it would be okay to use a pseudonym (for fear of reprisal from TFA or its far-reaching corporate associations), or ultimately decided either that their story was too difficult for them to share or that the use of a pseudonym would not be enough to shelter them from retaliation. This, to us, constitutes a great concern about the culture of control and fear that TFA instills into its corps members. If TFA is, in fact, interested in hearing and considering critique—as they claim (Villanueva Beard, 2013)—the experiences of many corps members and alumni who fear reprisal contradicts TFA’s claim of openness.

We hope this volume provides a unique and unfettered glance into TFA and provides some answers for those asking “Should I join TFA?” “Should my child join TFA?” “Should I hire a TFA corps member?” or “Should our district work with TFA?”

THE ROLE OF NARRATIVES IN TFA’S HISTORY

TFA has a well-established history of highlighting stories of “successful” corps members and alumni that, while admitting the difficulties of being a classroom teacher, serve largely as the primary foundation of organizational marketing, recruiting, and fundraising. In fact, Wendy Kopp’s most recent book (Kopp & Farr, 2011) makes a point of highlighting just a handful of anecdotal “stories” to prove that TFA is a force for good. And while there does exist a collection of corps ← 4 | 5 → members’ vignettes that cast TFA in positive light (Ness, 2004), until now there has not been a collection of counter narratives that not only provide relevant and valuable critique of the organization but also serve as balance in the conversation about corps members’ experiences in the organization. It is with this aim that we have collected counter narratives from alumni who represent a broad range of time periods, geographic regions, race/ethnicities, and genders. We have intentionally compiled a collection of narratives because

narratives, storytelling, and counter-stories can be transformative and empowering for educators, students, and community members. These methods can make public what many already know but have not spoken out loud: There are futures and lives at stake in the process we call education. (Fernández, 2002, p. 60) [Emphasis in original]

Because TFA has enjoyed more than 2 decades of positive rhetoric and financial support, the time has come when the voices of dissenters and critics can be heard. Based on the content of the chapters submitted for inclusion in this book, we have organized them into three main sections: (1) TFA’s Recruitment, Training, and Support Structure; (2) TFA’s Approach to Diversity; and (3) TFA’s Approach to Criticism and Critics (see Table 1). Authors in the first section share their early experiences with TFA as they were recruited and inducted into the organization. These narratives clearly demonstrate issues associated with a brief and ineffective teacher education, the lack of support structures as the corps members moved into their own classrooms, and the long-term impacts these experiences have had on their professional and personal lives. The chapters in the second section focus on their authors’ experiences of diversity within TFA, and the colonizing, racist, classist, and heteronormative values and practices that made their experiences in TFA difficult. Finally, the third section’s narratives focus on TFA as an organization that for years has relied on its belief in its own philosophy, resisting and attempting to silence its critics. To counter TFA’s successful public relations machine, we offer these narratives to inform potential corps members and their parents, philanthropic and corporate funders, and the policy makers who continue to support and finance TFA.

Details

- Pages

- IX, 216

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433128769

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453915561

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454192565

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454192572

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433128776

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1556-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (July)

- Keywords

- TFA Teacher Organisation corporate education neoliberal

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. IX, 216 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG