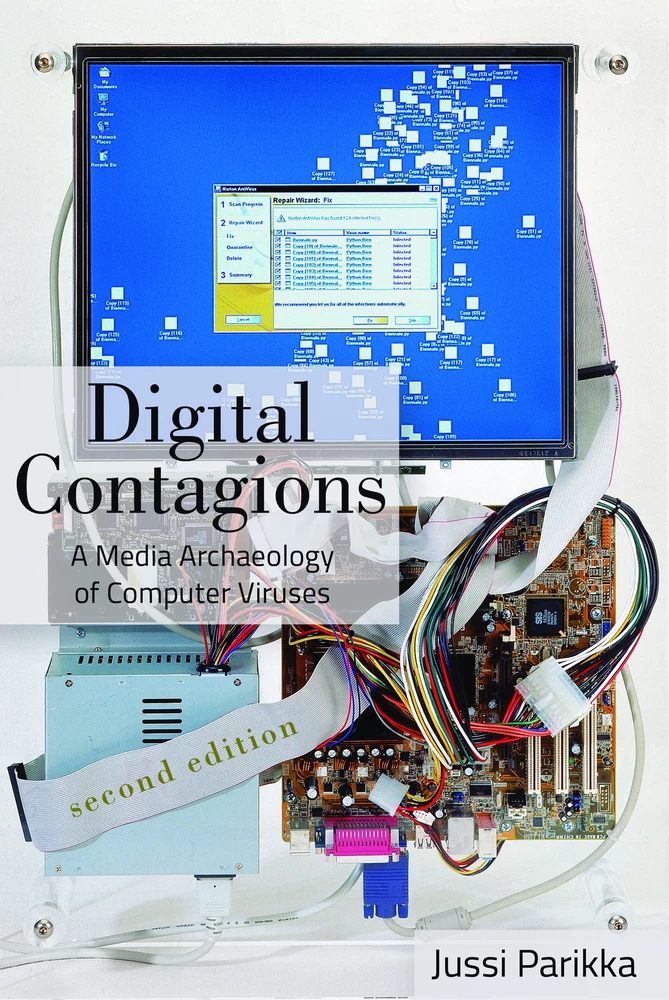

Digital Contagions

A Media Archaeology of Computer Viruses, Second Edition

©2016

Textbook

XL,

298 Pages

Series:

Digital Formations, Volume 44

Summary

Now in its second edition, Digital Contagions is the first book to offer a comprehensive and critical analysis of the culture and history of the computer virus.

At a time when our networks arguably feel more insecure than ever, the book provides an overview of how our fears about networks are part of a more complex story of the development of digital culture. It writes a media archaeology of computer and network accidents that are endemic to the computational media ecology. Viruses, worms, and other software objects are not seen merely from the perspective of anti-virus research or practical security concerns, but as cultural and historical expressions that traverse a non-linear field from fiction to technical media, from net art to politics of software.

Mapping the anomalies of network culture from the angles of security concerns, the biopolitics of computer systems, and the aspirations for artificial life in software, this second edition also pays attention to the emergence of recent issues of cybersecurity and new forms of digital insecurity. A new preface by Sean Cubitt is also provided.

At a time when our networks arguably feel more insecure than ever, the book provides an overview of how our fears about networks are part of a more complex story of the development of digital culture. It writes a media archaeology of computer and network accidents that are endemic to the computational media ecology. Viruses, worms, and other software objects are not seen merely from the perspective of anti-virus research or practical security concerns, but as cultural and historical expressions that traverse a non-linear field from fiction to technical media, from net art to politics of software.

Mapping the anomalies of network culture from the angles of security concerns, the biopolitics of computer systems, and the aspirations for artificial life in software, this second edition also pays attention to the emergence of recent issues of cybersecurity and new forms of digital insecurity. A new preface by Sean Cubitt is also provided.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction: The General Accident of Digital Network Culture

- Disease and Technology

- Media Theory Meets Computer Technology: Definitions, Concepts, and Sources

- Eventualization

- Section I: Fear Secured: From Bugs to Worms

- Prologue: On Order and Cleanliness

- Security in the Mainframe Era: From Creepers to Core Wars

- The Shift in Safety: The 1980s

- Fred Cohen and the Computer Virus Risk

- The Morris Worm: A Media Virus

- Viruses and The Antidotes: Coming to the 1990s

- Viral Capitalism and the Security Services

- Section II: Body: Biopolitics of Digital Systems

- Prologue: How Are Bodies Formed?

- Diagrams of Contagion

- The Order-Word of AIDS

- Excursus: Faciality

- Digital Immunology

- The Care of the Self: Responsible Computing

- The Psyche of the Virus Writer: Irresponsible Vandalism?

- Intermezzo: Viral Philosophy

- Section III: Life: Viral Ecologies

- Prologue: The Life of Information

- The Benevolent Viral Machine

- Cellular Automata and Simulated Ecologies

- Organisms of Distributed Networks

- Ecologies of Complexity and Networking

- Coupling and Media Ecology

- Afterword: An Accident Hard, Soft, Institutionalized

- Appendix: A Timeline of Computer Viruses and the Viral Assemblage

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Details

- Pages

- XL, 298

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433132322

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433135774

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433135781

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453918685

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1868-5

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (August)

- Keywords

- Computer viruses Computer worms Accident Technology Networks Internet Spam Malicious software Virus Security Media archaeology

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2016. XL, 297 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG