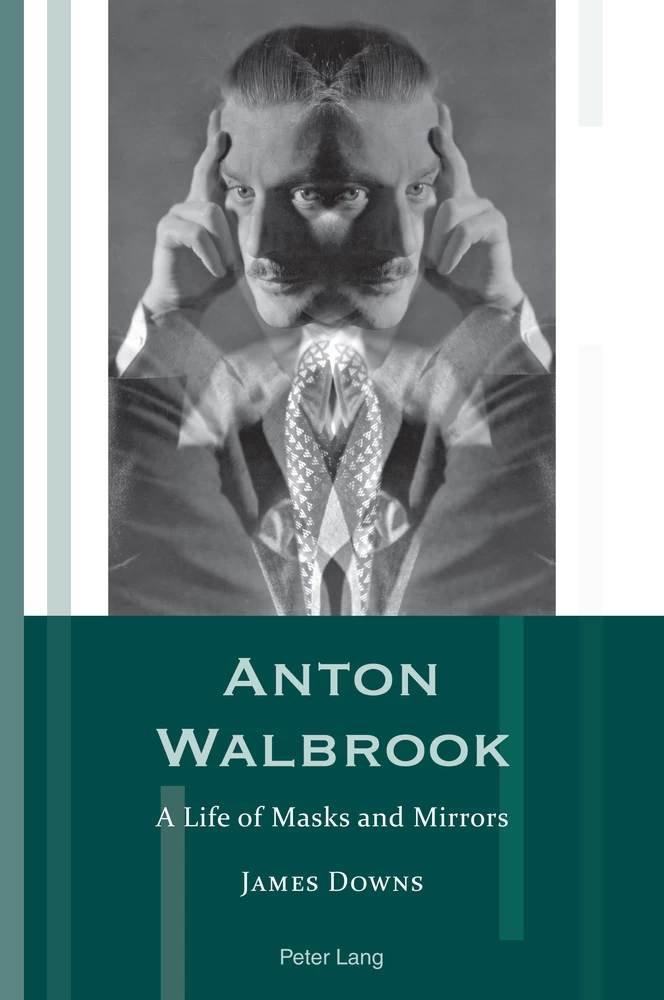

Anton Walbrook

A Life of Masks and Mirrors

Summary

«Few leading actors of classic cinema remain as enigmatic as Anton Walbrook, the subject of this very readable, frank and thoughtful biography. Despite Walbrook’s indelible performances in films such as the original Gaslight (1940), The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), The Red Shoes (1948) and La Ronde (1950), this is his first full-length biography, which makes it all the more welcome. There is much to discover in these pages about the Viennese-born star of German and British cinema with the ability to ooze charm or villainy at will, sometimes in the same breath.» (Pamela Hutchinson, Sight and Sound, June 2021)

«James Downs presents a fascinating and meticulously researched biography of a charming and darkly beguiling star who deserves our attention. It is enriched by archival evidence and images that illuminate Walbrook’s work as well as his equally intriguing, but carefully sequestered, private life; all refracted through his experience of exile.» (Professor Michael Williams, University of Southampton)

«It is often difficult to separate the elements of personal life and dramatic performance that create the star persona, but that of the stage and screen actor Anton Walbrook presents a unique and fascinating challenge. In his richly researched biography, James Downs brings a scholar’s authority and a fan’s enthusiasm to his subject, illuminating not only the career of one of British cinema’s most reserved stars, but the political and production background of his stage, screen and television performances in the UK and Germany.» (Mandy Merck, author of Cinema’s Melodramatic Celebrity: Film, Fame and Personal Worth, 2020)

Viennese-born actor Adolf Wohlbrück enjoyed huge success on both stage and screen in Germany during the 1920s and 1930s, becoming one of the first truly international stars. After leaving Nazi Germany for Hollywood in 1936, he changed his name to Anton Walbrook and then settled in Britain, where he won filmgoers’ hearts with his portrayal of Prince Albert in two lavish biopics of Queen Victoria. Further film success followed with Dangerous Moonlight and Gaslight, several collaborations with Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger – including his striking performance as Lermontov in The Red Shoes – and later work with Max Ophuls and Otto Preminger.

Despite great popularity and a prolific career of some forty films, alongside theatre, radio and television work, Walbrook was an intensely private individual who kept much of his personal life hidden from view. His reticence created an aura of mystery and «otherness» about him, which coloured both his acting performances and the way he was perceived by the public – an image that was reinforced in Britain by his continental background.

Remarkably, this is the first full-length biography of Walbrook, drawing on over a decade of extensive archival research to document his life and acting career.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Introduction and Acknowledgements

- Part I Wohlbrück

- Chapter 1 Circuses, Cloisters and Barbed Wire: Early Years, 1896–1919

- Chapter 2 ‘I suppose one doesn’t count as a human being without a uniform.’ Stage, Silence and Sound, 1920–1932

- Chapter 3 ‘You underestimate the lion.’ Stardom and Society, 1933–1934

- Chapter 4 ‘Sentimental Dreamer … one cannot change one’s own skin.’ Filmmaking under the New Regime, 1934–1935

- Chapter 5 ‘Will take the next ship … Useless to stop us.’ Leaving Germany for Hollywood, 1935–1936

- Part II Walbrook

- Chapter 6 ‘How can one live happily in a country that’s so difficult to get to?’ The Exile Arrives in England, 1937–1938

- Chapter 7 ‘I want to know more about the man!’ British Stage and Screen, 1939–1940

- Chapter 8 ‘You call us brothers.’ Europe, the USA and International Relations, 1941–1942

- Chapter 9 ‘This is not a Gentleman’s War.’ Playing ‘the Good German’, 1943–1945

- Chapter 10 ‘Time rushes by, love rushes by, life rushes by …’ War, Peace and Postwar Identities, 1946–1949

- Part III Life as Movement

- Chapter 11 ‘We’re in the past. I adore the past.’ Circles and Roundabouts, 1950–1951

- Chapter 12 ‘Everybody’s wearing masks.’ Myths of Mitteleuropa, 1952–1955

- Chapter 13 ‘Have you never thought of staying? Of resting? Settling down for a while?’ Saints and Sinners, 1955–1957

- Chapter 14 ‘The last chapter of my life has been written: a self-parody, naturally, with an ending like a third-rate kitsch operetta.’ First Steps on the Small Screen, 1958–1966

- Chapter 15 Song at Twilight: Final Performance, Death and Legacy

- Appendices

- Appendix 1: Filmography

- Appendix 2: Theatre Performances

- Appendix 3: Discography

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Figure 1. Postcard showing Wohlbrück in the role of

Armand in Die Kameliendame, Munich, 1920.

Figure 3. Wohlbrück in circus costume for the role of

Robby in Salto Mortale (Dupont, 1931).

Figure 7. Wohlbrück’s completed questionnaire 1933.

Bundesarchiv, Wohlbrück file.

Figure 8. Promotional material for the Spanish release of

The Courier of the Tsar.

Figure 9. Letter from Wohlbrück to Hans Weidemann, 9

November 1935. Bundesarchiv, Wohlbrück file.

Figure 12. Walbrook and Wynyard shredding Gaslight

script. Author’s collection.

Figure 15. Return to Germany – Walbrook arriving at

Hamburg airport, 1949.

Figure 16. Die Ratte poster (1950).

←x | xi→Figure 19. Der Fall Maurizius filming (Bern, autumn 1953).

Figure 20. Walbrook with Michael Powell during filming

of Oh … Rosalinda!! (1955).

Figure 21. As the Duke of Altair in Venus im Licht (TV

movie, 1960).

Figure 22. Walbrook as Waldo Lydecker in a scene from

the television movie Laura (1962).

Figure 23. Promotional adverts for Spanish-language

screenings of Walbrook’s films, 1950s.

Figure 24. Walbrook’s grave in St John’s Churchyard,

Hampstead. Photograph by author.

Introduction and Acknowledgements

It is impossible to pinpoint with certainty when I first heard the name of Anton Walbrook or watched one of his films. I remember watching Gaslight on television in my teens alongside my father, who was concerned that I might find the villainous performance upsetting. Once I discovered the wonders of Powell and Pressburger, I grew more familiar with Walbrook’s screen roles, but amidst the dazzling of array of talent in the work of the Archers he was but one of many outstanding players and my awareness of him remained shadowy until one particular day when I was working in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum at Exeter University.

I had begun volunteering at the museum, which was then known as the Bill Douglas Centre for Cinema and Popular Culture, in early 2009 and spent much of my time cataloguing donations from the museum’s co-founder Peter Jewell. Most of these were single items, but one morning I was confronted with a small collection of film memorabilia that had obviously been put together by someone who had been a fan of Walbrook in the 1930s, when he was a star of German cinema and went by the name of Adolf Wohlbrück. It consisted of assorted ephemera – cigarette cards, postcards, cinema programmes, film magazines and booklets, as well as a copy of a small pamphlet entitled Das Buch von Adolf Wohlbrück. If I had come across these items individually, or in the form of an online list or series of catalogue entries, they might still have made little impact, but laying them all out on the table in front of me made a profound impression.

Although I had been aware that he was, like many of the Powell and Pressburger regulars, an émigré from Nazi Germany, it was only when I saw ←1 | 2→this material that I realised he had been a major film star who was featuring on the front covers of German magazines and was significant enough to merit his own little monograph. I was at once curious: how did this part of his life relate to his later work in Britain? What must it have been like to leave a glittering career behind in one country and start afresh elsewhere, especially when one’s homeland and adopted country were at war with one another? There was a story here that I really needed to discover.

However, when I began trying to find out a little more about Walbrook’s life it soon became apparent that not only was there no published biography available, but acquiring the material for writing one was going to be a challenge. Although he had been the subject of a few book chapters, these had only concentrated on specific aspects of his career and did little to bridge the gap between the British and continental phases of his life. There were no collections of personal papers or diaries held in accessible archives, and the surviving correspondence – mainly of a professional nature – was scattered in fragments in different collections around the world. As I began tracking down as many of his films as I could to watch I also started to collect whatever I could find about him. As Peter Jewell, Bill Douglas and other collectors are aware, collecting is an addictive process that is impossible to stop once begun. For years I had been an inveterate collector of old books and ephemera, especially in relation to film, photography and visual culture, seeking out artefacts such as cartes des visites, glass negatives, magic lanterns and slides, 8mm projectors, old cameras, film reels and postcards. I actually discovered that I already had one or two Walbrook portraits in my collection, but began actively seeking out whatever else I could find. Some of this was acquired from well-known online auction sites but other items were successfully discovered from scouring through the boxes at postcard fairs and local antique shops, contacting antiquarian booksellers in Germany and placing adverts in different papers and periodicals seeking information from anyone who might have known Walbrook. Over the last ten years I have built up a fairly substantial collection, much of which has provided the raw material for this biography. These include cigarette cards, signed postcards, theatre programmes, cinema magazines – in German, French, English and other languages – from the 1930s to the present day, posters, ←2 | 3→lobby cards, film stills, promotional ephemera, vinyl records, 16mm film reels, scrapbooks, press cuttings, original letters, Walbrook’s film costumes and a small library of secondary literature covering the background to his life and career. Many of the cuttings are undated fragments, which explains why it has not always been possible to cite page numbers in the biography.

These materials have been augmented by those held in archives, libraries and museums both in the UK and abroad; and I must acknowledge the help I have received during my research from the staff of these institutions, as well as many other people who have assisted me in diverse ways. First of all, I must thank Dr Phil Wickham, the curator of the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, and Dr Helen Hanson, Associate Professor in Film History at Exeter University, whose friendship, knowledge and encouragement over the years have been a major force in writing this biography. I would also like to acknowledge the support over the years of Lisa Stead, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at Exeter, other colleagues including Eddie Falvey, Tom Fallows, Chris Grosvenor and Amelia Seely, Harald Nødtvedt for his translation of passages from the biography of Ferdinand Finne, Pauline McGonagle, Graham Howes and Karen Lynne, for the many friends and contacts who have shared with me their knowledge, memories and material relating to Walbrook’s life and career, including Astrid Bauer, Martine Dabkowski, Karen Margrethe Halstrøm and Mary Maxwell, Raphäel Neal, Paul Mazey, Beatrice Tiger, Inga Joseph, Daniel F. Brandl-Beck, Andreas Pretzel, Professor Alan Williams, Joel Finler, Dr Rosemarie Killius, Professors Ian Christie, Mandy Merck and Michael Williams, and for the numerous librarians, archivists and museum curators who have helped me access their collections and often provided assistance beyond the call of duty, including Sonja Wienen and Sigrid Arnold of the Düsseldorf Theatermuseum, Claudia Mayerhofer of the Vienna Theatermuseum, Babette Angelaeas and Kim Heydeck of the Deutsches Theatermuseum in Munich, Gerrit Thies of the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, Dr Karl Holubar, Nancy Mason of the University of New Hampshire, Storm Patterson and staff of the British Film Institute Reuben Library and Special Collections, Dashiell Silva, Thelma Schoonmacher, the representatives of the literary estates of Graham Greene, Michael Powell and Michael ←3 | 4→Redgrave for permission to quote from their writings, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II for permission to quote from material in the Royal Archives, to Dr Louise Styles for proofreading and to Christine Shuttleworth for compiling the index. Finally, to my editors at Peter Lang, Laurel Plapp and Andrea Hammel, whose support and solicitude has been of great help during the final stages of writing this book.

CHAPTER 1

Circuses, Cloisters and Barbed Wire

Early Years, 1896–1919

In March 1896 the Lumière Brothers, Auguste and Louis, brought their new invention to Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Cinématographe – a lightweight device combining camera, printer and projector – had been unveiled to the public in Paris a few months earlier and was now touring the world.1

The Vienna screenings opened on 27 March 1896 and followed the same pattern as in Paris, with a private show at the city’s k. k. Graphische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt [Graphic Research Institute] followed by public demonstrations at Kärtner Straße 45 in the city centre. These screenings ran throughout the day from 10 in the morning until 8 at night and, for a fee of fifty kreuzer, visitors could watch a selection of short documentary films accompanied by live piano music. To make the shows more attractive to Viennese citizens, the Lumière agents Alexander Promio and Alexander Werschinger filmed a series of sequences around the capital in early April: shots of St Stephan’s Cathedral, the huge Ferris wheel in the Prater (which would feature in The Third Man five decades later) and scenes of crowds strolling through the Stadtpark. A special screening of these was arranged for the Emperor Franz Joseph in the Hofburg on 18 April 1896. Werschinger recalled the scene:

We had a small room on the second floor of the Burg, as the palace is known, which we were able to try out two days in advance. The entire presentation was to be limited ←7 | 8→to five minutes, as it was feared that the flickering pictures could damage His Majesty’s eyes. It was also very difficult to explain to the attendant that the demonstration had to be carried out in the dark. He said that this was not possible because court protocol demanded that two candles should always be lit in the presence of His Majesty. Everyone was amazed that after he had seen the pictures, the Emperor demanded very animatedly that they be shown again twice.2

The cinema had arrived in Vienna.

Seven months later, in the same city, Adolf Anton Wilhelm Wohlbrück was born.3 Vienna was still buzzing with excitement over this new form of entertainment, but nobody at the time could foresee that ‘moving pictures’ would provide a career for the newborn child. Nor could they have foreseen that within twenty years the Emperor’s candles would be extinguished and his Empire dismembered. For the time being, Vienna was on the rise. Karl Lueger’s Christian Social Party had recently wrestled power from the Liberals and with Lueger as Mayor, Vienna began its transformation into a city of elegant gardens and parks. Artists, writers, musicians and other intellectuals met to discuss their views over coffee in Café Griensteidl, Café Central, or Café Museum. Prominent among these was a group known as Jung Wien [Young Vienna], whose members included the playwrights Arthur Schnitzler – then writing his controversial Reigen – and Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Egon Schiele was about to spearhead the Wiener Secession art movement, ‘Waltz King’ Johann Strauss the Younger – composer of the Blue Danube waltz, Die Fledermaus and Der Zigeunerbaron [The Gypsy Baron] – lived in Igelgasse, Freud had just coined the term ‘psychoanalysis’, Gustav Mahler had recently been appointed Director of the State Opera House, and cinema was the newest addition to the arts in which the Wohlbrück family had been involved for centuries.4

←8 | 9→The infant’s great-great-great-grandfather Johann Christoph Wohlbrück was born in Halberstadt in 1733. A simple craftsman, he nonetheless prospered to the extent that he was able to buy a house in Berlin on Leipzigerstraße.5 His son Johann Gottfried Wohlbrück (1770–1822) had a large family by his wife Marianne, including Gustav Friedrich Wohlbrück (1793–1849), an actor in Weimar whose daughter Ida Schuselka Brüning (1817–1903) was a famous actress and singer. Three of Ida’s daughters became actresses, while her granddaughter Olga Wohlbrück (1867–1933) was not only Germany’s first female film director – with Ein Mädchen zu Verschenken [A Girl as a Gift, 1913] – but also pursued a prolific career as an actress, novelist, screenwriter and theatre director.

Another of Johann Gottfried Wohlbrück’s sons was Wilhelm August Wohlbrück (1795–1848), an actor, director and composer who worked in theatres around Germany including Danzig, Königsberg and Lübeck. He remains best-known for the libretto Der Vampyr (1827), written for his brother-in-law Heinrich Marschner: Wilhelm’s sister Marianne Wohlbrück was a soprano and Marschner’s third wife. The two men collaborated on a number of operas, including Die Templer und Die Jüdin, based on Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe.

Wilhelm Wohlbrück had two daughters and ten sons, including Adolf Alexander Andreas Michael Wohlbrück (1826–97), who was born in Flensburg (or possibly Magdeburg) and worked as an actor and entertainer. He was the first to bear the name ‘Adolf’, which comes from the Old High German Athalwolf, a composition of athal, or adal, meaning noble, and wolf. He married Betty Lewien from Kiel, and on 2 May 1864 she gave birth to a son in Hamburg: Adolf Ferdinand Bernhard Hermann Wohlbrück was baptised in St Paul’s Lutheran Church, Hamburg, on 2 July 1864.6 Following the death of Betty Wohlbrück in 1869, the young ←9 | 10→boy was adopted by a musician – possibly because his father’s itinerant lifestyle made a stable upbringing impossible. Two years later a circus came to town and the sight of the entourage, with its tents, bands and animals, proved irresistible to the 7-year-old, who ran off to join them.7 In the early 1890s, having persevered with circus life and honed his skills in the art of clowning, Adolf transferred to the circus of Albert Schumann (1858–1939).

Born in Vienna, Albert Schumann began riding on horseback in the ring with his father – the equestrian Gotthold Schumann (1825–1908) – at the age of 3, but later set up his own circus company with premises in Malmö (1885), Copenhagen (1887), Vienna (1890), Berlin (1892) and Frankfurt (1893).8 Schumann originally established his circus in Vienna in the winter of 1890–1, setting up a wooden building in front of the Mariahilfer line – the old city boundary, within which higher taxes were levied – but the following year had a more permanent site constructed on Märzstraße.9 During his time working here with the Schumann circus, Adolf grew up to become a much-loved and well-known celebrity performer. Another clown, Adrian Wettach – better known as ‘Grock’ – recalled Adolf’s act: ‘He was very clever and his jokes were often astonishingly subtle; seconds passed before the public saw the point. When the laughter finally broke out, he made a little despairing gesture, as though to say “At last!” ’10 This subtlety, and skill in conveying feeling through minute gestures, would be inherited by his son.

At the age of 32, Adolf married Gisela Rosa Cohn, a 17-year-old girl from a respectable Viennese family. Born on 21 July 1879 in Vienna, she was the daughter of Wilhelm and Antonia Kohn.11 Her father – a ←10 | 11→merchant – had recently died, and it seems her parents had hoped for a better match: having a clown for a son-in-law was rather a disappointment. Nonetheless, Gisela fell pregnant almost immediately and their first child, Adolf Anton Wilhelm Wohlbrück, was born at their home at Jörgerstraße 32, in northwest Vienna, on Thursday 19 November 1896. He was baptised exactly a month later by Fr. Emil Janetzky, the parish priest of Hernals, with religion marked as ‘Catholic’ in the final column.12 Although it is frequently stated that Wohlbrück’s mother was Jewish – and the Kohn name clearly indicates Jewish ancestry – her family seem to have embraced Catholicism with ardour: Theodor Kohn (1845–1915), the Catholic archbishop of Olmütz, in Austro-Hungarian Moravia, was a close relative.13

Barely a year later, his sister Antonie Marie was born on 13 November 1897 – in Stuttgart, due to the itinerant nature of circus life. Gisela’s mother was unhappy with the prospect of her grandchildren spending their young lives on the road with a caravan of circus performers, and insisted that they remain in Vienna.14 In consequence, the siblings were raised largely by their grandmother Antonia, who lived in the same street. Later in life the actor revealed that his father had been a gambler who lost much of what he ←11 | 12→earned, which may also have explained some of his maternal grandmother’s disapproval.15

This did not, however, mean that young ‘Dolfi’ was unfamiliar with the circus. Later in life he recalled magical memories of watching his father perform – telling jokes with his characteristic deadpan expression – of seeing the famous equestrian James Fillis riding his horses around the ring, watching the dressage rider Baptista Schreiber and of a wonderfully wise elephant. Music appealed to him from an early age, and he would often wander into the circus tents to listen to performers practising on the guitar or concertina, where he would ask to try out the instruments.16 Despite his later insistence that he never seriously considered following his father into such work, he had to confess that ‘the circus ring was a kind of paradise for me.’17 What child could feel otherwise? Like most children, however, he was encouraged to conform to the more serious demands of education, and was duly enrolled at a monastic school about ten minutes’ walk from their home – the ‘Lazarenkloster’, run by the Christian Brothers in Schopenhauerstraße.18 The religious brothers made a deep impression upon him, and at one time he felt drawn to the priesthood. After all, the pulpit and the stage share much in common.

When Dolfi was seven the family moved to Berlin where he would remain for the next eleven years, although they returned regularly to stay with their grandmother in Vienna. The Wohlbrücks occupied two furnished rooms on Schumannstraße, and although living conditions were simple, the location was ideal from his father’s point of view as it lay only ←12 | 13→a hundred yards away from the circus.19 As a regular fixture at the Zirkus Schumann, he earned a monthly salary of 1500 Deutschmarks, although much of this was often squandered. On 6 October 1904 Dolfi and his sister were photographed together on their first day at school, and for the next eleven years he studied at the Friedrich Realgymnasium at 27 Albrechtstraße, on the corner with Schumannstraße. The Gymnasium system in Germany offered an education aimed at academically gifted students, strongly weighted towards the humanities. More importantly for his future career, however, the Deutsches Theater was situated just a few yards down Schumannstraße. Frau Wohlbrück became friends with the wife of Ernst Stern, set designer and art director at the theatre, and through these connections Dolfi became increasingly familiar with the theatrical world on his doorstep.

Meanwhile at school he obtained the Zeugnis der allgemeinen Hochschulreife or leaving certificate, known as the Abitur, which enabled him to enter university and was a sign that he was a student of some calibre. He particularly loved studying literature and the classics, and in addition to attempting to write a novel at the age of 14, he enjoyed reading out long passages to groups of schoolfriends, especially girls in his sister’s class. According to his sister Toni, at the age of 14 he fell in love with one of her classmates, Lotte Neumann, who was almost the same age and shared his interest in acting.20 Lotte later revealed that she had received her first kiss from Dolfi, who waited outside his school at the end of the day for the girls from the nearby Wagnerschule – attended by Toni and Lotte – to come out, when he might treat them to nougat bars bought for ten pfennigs from the Varsovie sweet shop on the corner of Karlstraße. Inspired by the ←13 | 14→proximity of the Deutsches Theater, the two girls got together with Dolfi to perform a play theatre at his house, using tablecloths and lamps provided by Frau Wohlbrück. Lotte began playing comic parts on the Berlin stage while still at school, singing from the age of 13 at the Komische Oper and the Komödienhaus, before making her first screen appearance in one of Max Mack’s silent films in 1912.21

Despite obtaining his Abitur, Dolfi left school at fifteen and chose instead to enter a drama school that had recently been opened at the Deutsches Theater by its director, Max Reinhardt (1873–1943). His acting talent was recognised quickly, for acceptance at the school was followed almost immediately by Reinhardt’s offer of a five-year contract at the same theatre. It has sometimes been claimed that he also received drama training in Vienna, although there seems to be little documentary evidence for this.22

Details

- Pages

- XII, 438

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789977110

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789977127

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789977134

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789977103

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16439

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (January)

- Keywords

- Anton Walbrook film and theatre/performing arts refugee & migration studies James Downs Anton Walbrook: A Life of Masks and Mirrors

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2020. XII, 438 pp., 5 fig. col., 20 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG