Teacher TV

Seventy Years of Teachers on Television, Second Edition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

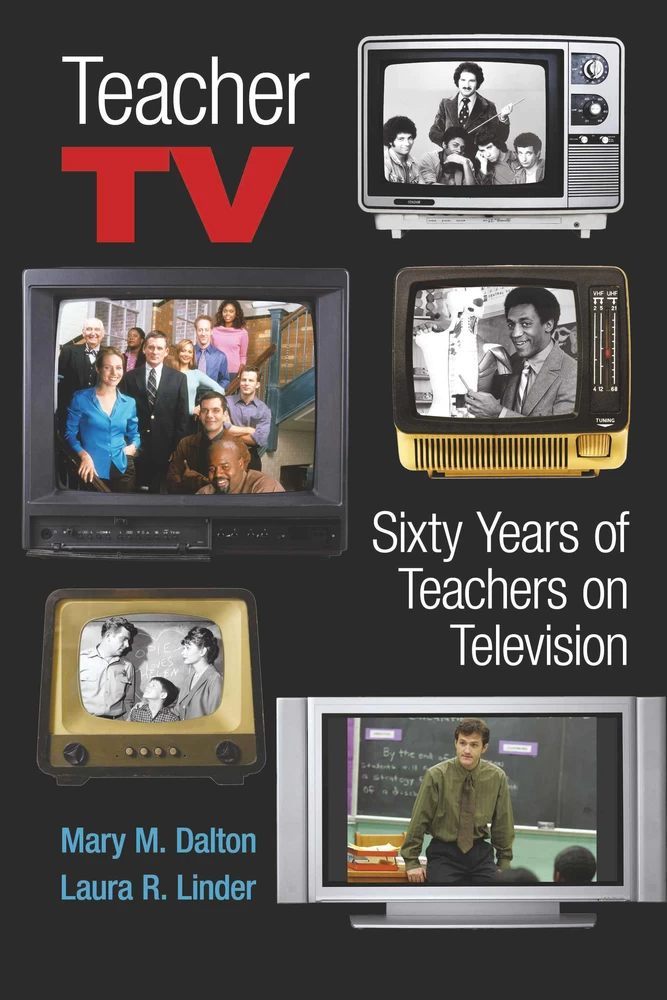

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One: Overview: Why TV? Why Teachers?

- Chapter Two: 1950s Gender Wars: Mister Peepers and Our Miss Brooks

- Chapter Three: 1960s Race and Social Relevancy: The Bill Cosby Show and Room 222

- Chapter Four: 1970s Ideology and Social Class: Welcome Back, Kotter and The Paper Chase

- Chapter Five: 1980s Normalizing Meritocracy: The Facts of Life and Head of the Class

- Chapter Six: 1990s Gaining Ground from Margin to Center: Hangin’ With Mr. Cooper and My So-Called Life

- Chapter Seven: 2000s Embracing Multiculturalism: Boston Public and The Wire

- Chapter Eight: 2010s Downward Spiral: From Madam Secretary to Teachers

- Chapter Nine: Afterword: Technology and Reclaiming the Teacher Narrative

- Index

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the support of our friends and colleagues, especially the ever-helpful staff at ZSR Library at Wake Forest University and at The Paley Center for Media in New York. We are grateful to Jon Kolnoski, who was an early champion of The Wire and to Laura Riddle for allowing us to cite a passage from her class journal.

The multiple readings and careful editing by Gary Kenton were immeasurably helpful at every stage of the process. When it came down to crunch time compiling screenshots for the book, Sherwood Jones really came through for us.

We cannot thank our families enough for their love and understanding during this process. To our friends in and out of our academic circles who have nurtured us and—by extension—this work every step of the way, many, many thanks. All those long hours, days, and months of work would have been much harder without your kind and supportive friendship.

Finally, to all our students throughout the years who have allowed us to be their teachers and to learn from them, we are grateful for the privilege of sharing our knowledge and experiences in the classroom. As teachers on television demonstrate so ably, the best learning process is always reciprocal.

Overview

Why TV? Why Teachers?

This book offers an examination of some of the most influential educator characters presented on primetime television over seventy years from the earliest sitcoms to contemporary dramas and web series. Both topical and chronological, this book focuses on dominant themes and representations within each decade from the 1950s through the 2010s. Although the chapters present an overview of the compendium of teachers on television for each decade, the focus of each chapter is a thesis that links some of the most popular shows of the era to larger cultural themes. Teacher TV is an extension of our earlier work and melds explorations of the cultural and curricular implications of how teachers are represented. Starting with The Hollywood Curriculum: Teachers in the Movies and continued in the anthology The Sitcom Reader: America Re-viewed, Still Skewed as well as articles and book chapters, we have thought deeply about the intersection of media, politics, identity, and education. Since the publication of the first edition of Teacher TV, we have also edited two volumes featuring essays about depictions of educators, Screen Lessons: What We Have Learned from Teachers on Television and in the Movies and Teachers, Teaching,1 and Media: Original Essays About Educators in Popular Culture.2 Even so, we have only scratched the surface in terms of examining important texts and making critical cultural connections. New to this edition are companion videos for each chapter. A link will be provided at the end of each chapter for that chapter video. This link will take you to the entire set of videos: https://vimeo.com/showcase/6916789

←1 | 2→Why TV?

Robert C. Allen poses the question in the introduction to Channels of Discourse Reassembled: “Why study television? For starters, because it’s undeniably, unavoidably ‘there.’ And, it seems, everywhere” (1). In Media Unlimited, Todd Gitlin talks about more than television when he argues that the “main truth” about media is that it “slips through our fingers” (4). It would be difficult to refute the importance of analyzing television texts and their larger contexts when considering something else Gitlin goes on to say: “The obvious but hard-to-grasp truth is that living with the media is today one of the main things Americans and many other human beings do” (5). The very obviousness of this condition is precisely what causes people to take television and other media for granted. For our purposes, television is a much more expansive term than it was a decade ago when the first edition of this book was published. The term television is shorthand for visual narratives that arrive in our homes or on smaller screens we take with us anywhere and everywhere. With the introduction of different platforms for engaging with visual narratives, viewers have more choices and more ways to access series than ever before, but the reasons we give them our attention may not be so different after all. Gitlin maintains that we spend so much time engaging media not for information but for “satisfaction, the feeling of feelings” (5–6). Stories tell us who we are and how we fit into the rest of the world, a world partially constructed by those same stories. We believe the result is not mere stimulation but—intended or not—inculcation from the repetition of specific patterns of representation across time and, in some cases, across media.

Our purpose here is to look critically at patterns of representation of teachers. These are patterns that many people “know” and tacitly accept without considering carefully and often without making connections among these television shows, relevant historical topics, and ideologies. Visual texts with moving images have become the dominant textual forms of contemporary global culture, a condition that was true ten years ago and that has been compounded by the explosion of social media. Liberal education today must include developing in students the ability to decode and interrogate visual texts and, optimally, learning to produce them as a means of empowerment. Critical viewing is necessary for consumers of popular culture, but the power to produce goes further and is democratizing. We continue in this second edition of our book with what is necessary—viewing critically—and introduce a few concepts here in the first chapter that will serve as useful tools for explicating the television shows that feature important educator characters: intertextuality; competing messages; and, genre and the popular.

←2 | 3→Intertextuality

We know that media—and our particular focus on television in the expansive meaning of the term—is ubiquitous but so, very nearly, is schooling. One might point to the growing number of students who are home-schooled and not exposed to professional teachers, but even these students likely have occasion to encounter teachers on television and know about group classrooms if only through stories shared by others and field trips with other homeschoolers. Most of us, in fact, will encounter more teacher characters over time in mediated classrooms than actual teachers in our own classrooms, and there are certain lessons we learn from these many fictional educators. This is also the case for teacher education students (and for actual classroom teachers). In the article “Culture and Pedagogy in Teacher Education,” Ronald Soetaert, Andre Mottart, and Ive Verdoodt discuss exercises they use in a teacher education program to help reveal “literacy myths” in popular texts:

One of the possible ways to make students aware of the politics of representation is to confront them with the ways—for example—in which “teachers” are represented in literature, movies, advertising, television, and so on. In our teacher training course we invite students to collect material from different media in which teachers and literacy practices and events are represented. (163)

Others, have written about their choices to use popular teacher films in teacher education programs for similar reasons, including: Dierdre Glenn Paul; Raúl Alberto Mora; Jill Ewing Flynn; and Jacqueline Bach and Susan D. Weinstein. Scholars Christian Z. Goering and Shelbie Witte show media texts (such as the 2002 film Blue Car) to teacher candidates to introduce issues of educator misconduct and give students practical examples of “grooming” behaviors to help them keep a protective eye on future colleagues. While Henry Giroux is framing an argument about the value of studying films when he notes that their “popularity and widespread appeal” are precisely what “warrants an extended analysis” (147), we believe that premise applies equally to television for the same reasons and that these texts may merit even more consideration because of the accessibility of television. We see media and culture as indistinct constructs swirling together and sometimes merging as we, individually and collectively, draw on the narratives we encounter as “scripts” that are filled with both limitations and possibilities for our lives, scripts that provide patterns we draw upon in creating our identities and worldviews.

Viewing media is an active process, a reading of the visual text. Media texts never exist separate from contexts, including a reader’s own lived experience, and that lived experience is similarly informed by many other media texts and personal ←3 | 4→narratives. The texts under consideration here, television series featuring educators, are incorporated into the reader’s everyday life at the same time the reader’s everyday life becomes part of the construction of the text. John Fiske writes in Understanding Popular Culture:

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 290

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433170164

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433170188

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433170195

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433170201

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15729

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (June)

- Keywords

- Lehrer Bildungssendung Fernsehsendung Geschichte teaching school education television gender race teacher

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XVI, 290 pp., 27 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG