Linguistische Beiträge zur Slavistik

XXIV. JungslavistInnen-Treffen in Köln, 17.-19. September 2015

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Autoren

- Über das Buch

- Zitierfähigkeit des eBooks

- Inhaltsverzeichnis

- Vorwort

- How words meet signs: A corpus-based study on variation of mouthing in Russian Sign Language (Anastasia Bauer)

- Zur Frage potentieller turkisch-russischer Sprachkontakte (Alexander Böhnisch)

- Zur Analyse von Internetkonversationen (Genia Böhnisch)

- Agent prominence in the Polish -no/-to construction (Daniel Bunčić)

- Language ideology and linguistic manifestations of gender conceptualisations in Croatian (Roswitha Kersten-Pejanić)

- Förderung der Textkompetenz in der Herkunftssprache: Überlegungen zum Bosnisch/Kroatisch/Serbisch-Unterricht im deutschsprachigem Raum (Ivana Lederer)

- Wh-infinitive constructions in Russian, Belarusian and Lithuanian (Lidia Mazzitelli)

- Perfekt, Präteritum, Evidentialität: l-Formen im Südostslavischen (Anastasia Meermann)

- Zur sprachenpolitischen und kontaktlinguistischen Situation des Romani in Russland (Anna-Maria Meyer)

- Der Skandaldiskurs zu FEMENs Protestaktionen: Ein Blick auf die ukrainische Kultur (Marianna Novosolova)

- Die Struktur von Experiencern und andere empirische Befunde zur russischen Elementarkonstruktion (Katrin Schlund)

- Die AutorInnen im Bild

How words meet signs: A corpus-based study on variation of mouthing in Russian Sign Language

Резюме

В статье обсуждается феномен использования слов звучащего языка в жестовых языках (в виде беззвучной артикуляции, или маусинга) и представляется обзор лингвистических исследований этого феномена. Этот феномен еще недостаточно изучен в жестовых языках и вопрос о его лингвистическом статусе является весьма актуальным. Исследований, посвященых этому феномену в русском жестовом языке (РЖЯ), на данный момент не существует. Эта статья приводит аргументы в пользу использования корпусных исследований для изучения (беззвучной) артикуляции в жестовых языках. В центре внимания статьи — первый анализ этого феномена на примере двадцати частотных жестов в корпусе РЖЯ. Наш анализ артикуляции в РЖЯ показывает, что жесты РЖЯ часто сопровождаются русскими словами или их частями, что описано и для других жестовых языков. Более того, РЖЯ отличается более низкой частотой использования артикуляции в проанализированных жестах. Данное исследование также показывает интересную особенность артикуляции в РЖЯ: использование в артикуляции именного склонения.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of mouthing in sign languages has received a lot of attention in the last decades and it continues to be an area of fruitful research and controversial debates especially with regard to its linguistic status as well as consistency of production (Bank et al. 2011, 2016; Mohr 2014; Johnston et al. 2016; Giustolisi et al. 2016). Despite the fact that mouthing is an integral part of communication between native Deaf signers in natural conversation without hearing people present (Bank 2014), this phenomenon is still far from being thoroughly understood. In particular, the level of integration and conventionalization of mouthing into the sign language system is still not clear to linguists. This paper adds novel data by looking at mouthing in Russian Sign Language (Russian Русский жестовый язык or РЖЯ; henceforth: RSL). Mouth actions in this language have never been studied before. Furthermore, this paper highlights the latest tendencies on mouthing research and points out how corpus-based approaches contribute to the analysis of mouthing.

The paper is organized as follows: after a short introduction to the phenomenon of mouthing in 2, I provide an overview of research on mouthing in sign languages in section 2.2. Section 3 specifically addresses the disagreements on the linguistic status of mouthing. Section 4 briefly introduces the recent corpus ← 9 | 10 → approaches to mouthing research. In Section 5 I give some sociolinguistic background on RSL and describe the methodology, and present the research questions and findings. Sections 6 and 7 debate and summarize findings of this paper.

2. The phenomenon of mouthing

Mouth movements that resemble the articulation of a spoken word are known as mouthings in sign language research (Boyes-Braem & Sutton-Spence 2001). For example, in German Sign Language (Deutsche Gebärdensprache, DGS) the manual sign MAN is usually accompanied by the mouthed word Mann ‘man’ with or without vibration of the vocal cords (voicing) or air turbulence (whispering)1. Several authors have explored this phenomenon with data from different sign languages, yet still mouthing patterns and their grammatical functions are not fully understood. Two pioneering studies on mouthing (Vogt-Svendsen 1981 for Norwegian Sign Language and Schermer 1990 for the Sign Language of the Netherlands (Nederlandse Gebarentaal, NGT)) inspired a book edited by Boyes-Braem & Sutton-Spence (2001), where the authors focus entirely on mouth patterns in various sign languages. Their work has laid the ground for further research of this unique sign language phenomenon. Boyes-Braem & Sutton-Spence (2001) standardize the terminology mouthing and mouth gestures for two different types of mouth patterns and gather research on mouthing in nine different sign languages: British, Finnish, German, Italian, Norwegian, Swedish, Swiss-German (Deutschschweizerische Gebärdensprache, ← 10 | 11 → DSGS), NGT and Indo-Pakistani Sign Language (IPSL) (Sutton-Spence & Day 2001; Raino 2001; Ebbinghaus & Heßmann 2001; Ajello et al. 2001; Vogt-Svendsen 2001; Bergmann & Wallin 2001; Boyes-Braem 2001; Schermer 2001; Zeshan 2001). More recently, there have also been three comprehensive corpus investigations of mouthing (Mohr 2014 for Irish Sign Language; Bank 2014 for NGT; Racz-Engelhardt 2016 for Hungarian Sign Language; see section 4 for details).

2.1. Terminology issues

The terminological divergences that were present in the middle of the 1990s (i.e. oral or spoken components, word pictures, visual mouth segments) appear to have been solved and the term mouthing describing mouth movements that have a relationship with a spoken language has become generally accepted among linguists2. In the linguistic literature on Russian Sign Language there is no established corresponding terminology for the two different types of mouth patterns and no studies on the use of mouth actions in RSL have yet been carried out. Occasionally one comes across the English term маусинг (mouthing in Cyrillic). In Bauer (2018) I suggest using in Russian the term artikuljacija ‘articulation’ to refer to the phenomenon of mouthing and the term žesty rta ‘gestures of the mouth’ to refer to mouth gestures, which are not associated with the articulation of spoken words.

2.2. Mouthing research

Facial activities or non-manual signals carry important lexical, prosodic, morphological and syntactic information in sign languages (Pfau & Quer 2010; Herrmann & Steinbach 2011; 2013). The growing research on mouthing in the last decades has shown that they contribute significantly to the formal and semantic aspects of sign languages. Mouthing may “specify or complement the meaning of the sign” or “disambiguate minimal pairs” (Schermer 2001: 277). Mouthing also has different stylistic functions in sign languages (cf. Boyes-Braem & Sutton-Spence 2001; Balvet & Sallandre 2014) and may indicate sociolinguistic differences within a language community (Mohr 2014). The use of mouthing has been documented for various sign languages around the world (Crasborn et al. 2008; Nadolske & Rosenstock 2007; Zeshan 2001) with the exception of Kata Kolok, a village sign language of Northern Bali, which is reported to use no mouthing (De Vos & Zeshan 2012: 17). ← 11 | 12 →

Mouthing historically originated as borrowing from the surrounding spoken language3 (Mohr 2012; Quinto-Pozos & Adam 2015). However, signers do not simply use a spoken language while producing a mouthing. They rather use a feature of their sign language that has been derived from a spoken language (Sutton-Spence 2007).

The prevalence of mouthing in Deaf native signing is striking (Bank et al. 2011, 2016). A DGS Corpus analysis showed that more than 80% of all utterances contain a least one mouthing. That is, every second manual element in a usual signed utterance is accompanied by a mouthing in DGS (Ebbinghaus & Heßmann 1995). The Australian Sign Language (Auslan) data show that more than 70% of all mouth actions are in fact mouthings and a recent corpus-based NGT study identifies 80% of all mouth actions with manual signs as mouthings (Johnston et al. 2016; Bank 2014).

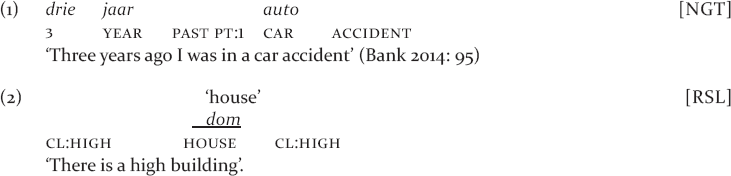

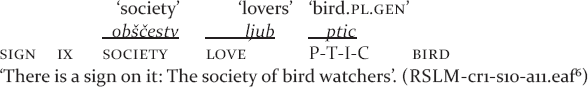

In most cases, mouthings correspond exactly to the manual sign both in terms of temporal alignment and semantic congruency. The most frequent type of mouthing is, thus, semantically congruent or redundant (Schermer 1990; Boyes-Braem 2001; Bank et al. 2011; Mohr 2014). It is illustrated by the NGT mouthings drie4 ‘three’, jaar ‘year’, auto ‘car’ and the RSL mouthings dom ‘house’, obščestv(о)5 ‘society’, ljub(itelej) ‘lovers’ and ptic ‘birds’, which all have the same (or a related) meaning as the manual signs they co-occur with in (1)–(2):

2.2.1 Reduced mouthing

In terms of form, mouthing may be fully pronounced, temporally reduced, repeated or spread across adjacent manual signs. A mouthing is considered reduced when its parts are invisible, as in the DGS examples wi(chtig) ‘important’, fer(tig) ‘ready’ or NGT aksp for accepteren ‘to accept’ (Boyes-Braem 2001: 104; Bank 2014: 24). Research shows that unstressed syllables are reduced more often and temporal reduction thus typically happens in the form of deleting word-final consonants (Bank et al. 2011; Johnston et al. 2016). Mouthings may be reduced to a single syllable or to very short mouth movements as in the NGT example zien ‘see’, which is reduced to only z (Bank 2014: 38). Schermer (1990) even suggests that temporally reduced mouthings are similar to mouth gestures, since they are no longer identifiable by themselves as spoken lexical items.7 Ebbinghaus & Heßmann (1995) observe that in DGS reductions occur more often on verbs than on nouns. They assume that a reduction of a German verb does not impair the understanding of the meaning in the same way as the reduction of a noun does.

Furthermore, Sandler & Lillo-Martin (2006: 105) reason that reduced mouthings apparently conform to the rhythm of the monosyllabic form of the sign. This, however, does not explain the variation of reduced mouthings as found in Bank et al. (2011). Bank et al. show that the reduction of mouthings in NGT occurs on the stressed syllable of the Dutch word, suggesting that signers have knowledge of the rhythmic structure of Dutch words. Whether the signers have access to the prosodic information of spoken words, however, is still a matter of further research and can best be tested in future investigations in a sign language surrounded by a spoken language with a different word stress pattern.

Russian Sign Language lends itself well to researching reduced mouthing, since in contrast to Germanic word stress patterns, where the first syllable is usually stressed, spoken Russian is a free-stress language, i.e. the stress can fall on any syllable in a word. Additionally, due to the vowel reduction phenomenon in Russian, vowel quality varies greatly depending on whether the vowel occurs in stressed or in unstressed syllables (Yanushevskaya & Bunčić 2015). Therefore, the reduction of mouthing in RSL calls for research. ← 13 | 14 →

2.2.2 Inflected mouthing

Mouthings have typically been observed and described without any inflectional markings. Previous sign language research accounted for occurrences of inflections in mouthing only as exceptions (Ebbinghaus & Heßmann 1995; Zeshan 2001; Hohenberger & Happ 2001). Mohr (2014) reports on the occurrence of inflected mouthing with examples of tense marking on verbs, e.g. the mouthing left co-occuring with the sign LEAVE, and plural marking on nouns, e.g. the mouthing holidays with the sign HOLIDAY (see also the occurences of “frozen forms” in Sutton-Spence 2007).

The use of inflected forms for any morphosyntactic categories in mouthings would suggest that not only the lexicon of the spoken language is activated during signing, but also its grammar. A recent corpus study by Racz-Engelhardt (2016) demonstrates the frequent use of inflected mouthings by Hungarian Sign Language signers. The mouthed verbs and nouns in Hungarian Sign Language are frequently inflected for person, number and case.

2.2.3 Mouthing and word class

Mouthings are usually reported to accompany nouns and morphologically simpler signs more frequently than verbs or morphologically complex signs (such as spatial verbs with classifier constructions). In studies of noun-verb pairs in Austrian Sign Language (ÖGS) and Auslan, it was noticed that mouthing is much more likely to occur with nouns than with verbs. In Hunger’s (2006) study of ÖGS, 92% percent of the nouns and only 52% of the verbs were accompanied by mouthing. In Auslan, about 70% of the nouns were accompanied by mouthing, but only 13% of the verbs (Schembri & Johnston 2007). Similarly, Kimmelman (2009) has already found that in RSL mouthings accompany nouns much more often than verbs and noted that mouthing can be called a reliable criterion to distinguish word classes in sign languages (mostly nouns from verbs; cf. also Voghel 2005, Schwager & Zeshan 2008). A recent corpus study by Bank et al. (2011), however, finds no word class specific pattern in their corpus study of NGT mouthings. Instead, the authors observe an alternate use of mouthings and mouth gestures accompanying adjectives and nouns (we could not confirm Bank et al.’s (2011) observation for RSL, see section 6.1).

2.2.4 Sociolinguistic factors

It terms of sociolinguistic factors, the influence of particular aspects has been found to have a significant effect on the use of mouthing. Gender and age were clearly the most important factors for Irish Sign Language (ISL) (Mohr 2012, 2014). Men tend to use fewer mouthings than women in ISL. Age has also been found to have an effect in the New Zeeland Sign Language (NZSL; McKee & ← 14 | 15 → Kennedy 2006). A preliminary analysis of variation in mouthing in NZSL shows that signers over the age of 65 years accompany an average of 84% of manual signs with mouthing components, compared to 66% for signers under 40 years. Within NGT no age, gender or nativeness-related differences in the use of mouthings were found. Bank et al (2016) did find an effect both for region and for the level of education in that higher-educated signers used fewer mouthings. Nadolske & Rosenstock (2007) found more mouthings in interactive than in narrative registers of the American Sign Language (ASL).

3. The linguistic status of mouthing

The linguistic status of mouthing continues to be an area of controversial debate in the current sign language literature (Capek et al. 2008; Bank et al. 2011, 2016; Hosemann 2015; Johnston et al. 2016; Giustolisi et al. 2016). The continuum of opinions ranges from mouthings as instances of online code-blending, where signers can freely and simultaneously combine elements from a spoken and signed language, to mouthings as part of a sign’s phonological description just as other phonological formational categories of hand configuration, location and movement. Several authors thus consider mouthing to be an inherent part of the sign language lexicon (e.g. Boyes-Braem 2001; Sutton-Spence & Day 2001; Ajello et al. 2001; Vogt-Svendsen 2001), whereas other researchers argue that mouthings should not be regarded as part of the lexicon (Hohenberger & Happ 2001; Ebbinghaus & Heßmann 2001; Vinson et al. 2010; Bank 2014).

According to the first view, mouthings are interpreted as loan elements from the surrounding spoken language, which have become fully integrated and embedded into the system of manual signs. Under this view, mouthings, being completely integrated in the sign language production system, may be reduced, spread or repeated to maintain alignment with the duration and rhythm of the signs’ manual components (Boyes-Braem 2001; Vogt-Svendson 2001).

According to the second view, Hohenberger and Happ (2001) claim that mouthings are not a part of the sign language system but are rather phenomena of language performance. They reason that mouthings originated in oralist education and should therefore be regarded as an incidental consequence of language contact. Under their view, mouthings are not part of the sign lexicon and are, thus, not linguistically relevant.

Ebbinghaus & Heßmann (2001) take an alternative view by proposing a semiotic model for sign language systems, according to which signing is multidimensional communication, where mouthing is a meaningful component together with manual signs and non-manual elements. Due to the high frequency of mouthings and their contribution to the meaning of the sign, Ebbinghaus & Heßmann (2001) interpret mouthings as an integral part of DGS signs. ← 15 | 16 →

Keller (2001) illustrates another viewpoint by suggesting a kinematic analysis which treats mouthing as visual units rather than spoken words.

3.1. Mouthing as an integral part of the phonological representation of signs

The views presented above amount to the overarching question whether or not mouthings are specified in the lexicon of sign languages. There are arguments for both sides.

One of the arguments supporting the hypothesis that mouthing is an intrinsic part of the linguistic system of sign languages is that mouthings are not always semantically congruent with the manual signs they accompany. Thus, mouthing can add extra semantic information to the sign (Sutton-Spence & Woll 1999). The Auslan sign SPOUSE can, for example, be specified with the English mouthings wife or husband (Johnston & Schembri 2007). Mouthing can thus be used as a device of specification. Vogt-Svendsen (2001: 22) gives the example of the Swedish word for ‘white’ being mouthed along with the Swedish Sign Language sign AREA to mean ‘white area’.

Another argument for considering mouthing as a part of the lexical/phonological specification of a sign is their phonemic value. Mouthing can distinguish minimal pairs of signs. Many signs in DGS, like e.g. BROTHER and SISTER, are produced with an identical handshape, orientation, location and movement. Many such otherwise polysemous signs can be distinguished by an accompanying mouthing. A similar example for using mouthing as a device for disambiguation is found in Adamorobe Sign Language, a village sign language in Ghana, where the signs for BLACK, WHITE and RED, being manually identical, are distinguished by mouthings (Nyst 2007).

Several recent experimental studies provide further evidence for the assumption that mouthings are an integral part of the phonological representation of signs (e.g. Capek et al 2008; Hosemann 2015). An ERP study by Hosemann (2015) reveals the co-activation of spoken language during the processing of sign language sentences by deaf native signers of German Sign Language. The participants in Hosemann’s study were presented DGS examples without any overt mouthings on prime or target signs to exclude the co-activation of German translations. Nonetheless, a significant priming effect was observed and showed that the orthographic/phonological representation of German words is activated during DGS processing. Hosemann accounts for this bimodal priming effect by assuming mouthing to be a part of the sub-lexical representation of the sign (as well as of the spoken word). ← 16 | 17 →

3.2. Mouthing as an instance of code-blending

There are, however, observations which are not easily compatible with the view that mouthings are specified in the sign language lexicon. One of these is the study by Bank et al. (2011) on variation in mouth actions with manual signs. While a steady simultaneous occurrence and synchronization of mouthings and manual elements may suggest a fixed shared lexical representation of sign and mouthing, high variability in the combination of mouthings and manual signs provides strong evidence against an account positing that mouthings are a part of lexical signs. In an NGT Corpus study Bank et al. (2011) find substantial variation in mouthings not only in timing (i.e. temporal reduction) but also in the type of mouth actions. Signs in NGT can apparently be combined with either mouthing or mouth gesture depending on the context (Bank 2014: 42). The sign CI, for example, was equally accompanied by mouthing and mouth gesture in 42 percent of its tokens. The sign GROUP was accompanied in 21 percent of its tokens by mouthing and in 31 percent by mouth gestures. This alternative use of mouthing and mouth gestures led the authors to claim that there is no fixed form of a mouthing accompanying a sign. Bank et al. (2011) thus argue in favor of the assumption that mouthings are not part of the lexical entry of a sign but are rather instances of code-blending8 (Bank et al. 2011; Bank 2014).

Details

- Pages

- 214

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631784532

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631784549

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631784556

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631784563

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15394

- Language

- German

- Publication date

- 2019 (April)

- Keywords

- slavische Sprachen Sprachkontakt Genderlinguistik Semantik Herkunftssprache Syntax

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2019. 214 S., 32 s/w Abb., 10 Tab.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG