Ferramonti

Interpreting Cultural Behaviors and Musical Practices in a Southern-Italian Internment Camp

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

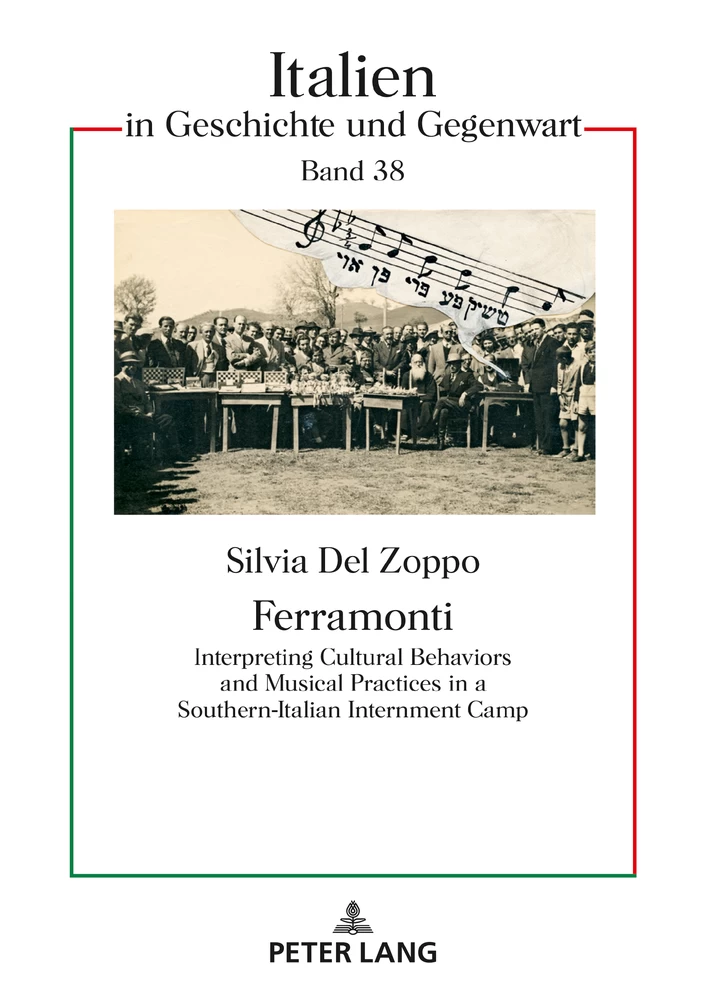

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Autorenangaben

- Über das Buch

- Dedication

- Dedication1

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Zusammenfassung

- Abstract

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Limits of Representation and Representation ofLimits

- 1.1 A Survey of Existing Research

- 1.2 “Lagermusik”: A Definition?

- 1.3 Shoah Representations through the Arts

- 1.4 Looking for Meaning: A Hermeneutic Approach

- Chapter 2 On the Ferramonti Trail

- Chapter 3 Historical Insights

- 3.1 Discrimination, Persecution and Internment

- 3.2 The Promulgation of Racial Laws in 1938

- 3.3 Aspects of the Persecution of Jews in Italy

- 3.4 Fascist Propaganda and Consensus in the South of Italy

- 3.5 The Geography of Fascist Internment Camps between 1940 and 1943

- Chapter 4 Ferramonti: The History of the Camp

- 4.1 The Building of the Camp

- 4.2 A Steamboat to Palestine

- 4.3 Aid Organizations

- 4.4 The Camp between January 1942 and September 1943

- 4.5 General Camp Rules and Regulations in Ferramonti

- 4.6 Liberation, Fort Ontario and Other Destinations

- Chapter 5 Concert Schedule and Musical Programs at Ferramonti

- 5.1 Musical Performances in Sonnenfeld’s and Lopinot’s Memoirs

- 5.2 Concert Programs in the Kalk Archive: The Early Years

- Chapter 6 Musical Practices and Everyday Life

- 6.1 Lieder, Schlager and Popular Songs

- 6.2 Jazz and Kabarett

- 6.3 Radio Broadcasting and Popular Music

- 6.4 Variety Shows and the Concert of the Austrians in 1944

- 6.5 The Ferramonti Schule and Musical Education in the Camp

- 6.6 After Liberation: The Charity Concert in Cosenza

- 6.7 Musical Performances on Jewish Feasts

- Chapter 7 Musical Instruments in the Camp

- 7.1 A Gift from Mensa dei Bambini: The Grand Piano

- 7.2 Calabrian Lutherie on Demand

- 7.3 A “Reed” War Good

- Chapter 8 The Interned Musicians: A Small Portrait Gallery

- 8.1 Adler, Michael (Subotica, October 5, 1924)

- 8.2 Behrens, Walter (Karlsruhe, January 30, 1901)

- 8.3 Eisenhardt, Manfred (Breslau, December 27, 1912)

- 8.4 Englander, Samuel (Dobje, June 19, 1913)

- 8.5 Falk Hoffmann, Anita (Bad Godesberg (Bonn), January 15, 1906)

- 8.6 Finger Weisz, Livia (Budapest, October 25, 1908)

- 8.7 Friz, Leo (Mirski, Lav) (Zagreb, June 21, 1893)

- 8.8 Gildingorin (Gorin), Paul (Leipzig, July 19, 1916)

- 8.9 Glattauer, Viktor (Vienna, January 19, 1909)

- 8.10 Gornicki, Moisze (Zgierz, June 13, 1919)

- 8.11 Grünstein, Josef (Cinoves, October 19, 1919)

- 8.12 Klein, Oscar (Graz, January 5, 1930)

- 8.13 Laqueur Silberstein, Elly (Brieg, February 13, 1901)

- 8.14 Levitch, Leon (Belgrade, July 7, 1923)

- 8.15 Lipovicz, Leszek (Warsaw, February 27, 1924)

- 8.16 Marton, Rudolf (Sarajevo, November 11, 1916)

- 8.17 Messerschmidt, Adolf (Berlin, March 10, 1890)

- 8.18 Metzger, Jeremias, (Przemyśl, June 2, 1903)

- 8.19 Perl, Lazar (Bratislava, December 6, 1919)

- 8.20 Schiff Lazar, Anny (Vienna, December 17(27), 1921)

- 8.21 Sonnenfeld, Kurt (Vienna, February 24, 1921)

- 8.22 Steinbrecher, Ellen (Berlin, March 17, 1924)

- 8.23 Steinfeld, Sigbert (Berlin, January 13, 1909)

- 8.24 Sternberg, Ladislav (Brčko, July 3, 1914)

- 8.25 Thaler, Isak (Bohorodchany, January 17, 1902)

- 8.26 Weiss, Bruno (Brčko, November 22, 1909)

- 8.27 Zins, Bogdan (Stanisławów, November 21, 1905)

- Chapter 9 In Response to the Aporias of Internment Camps: Musical Practices as Cultural Behaviors

- 9.1 Music and Internment: Comparisons and Contrasts with Other Camps

- 9.2 Musical Performances in Ferramonti: Specific Features

- 9.3 Beyond Music: Other Cultural Practices and Visual Sources

- 9.4 The Shoah through Music and Literature: Amid Representation and Commemoration

- 9.5 Evading the Paradoxes of the Auschwitz Paradigm: Aesthetic Perspectives on Music in Captivity

- Appendices

- Bibliography

Zusammenfassung

Ferramonti di Tarsia (Cosenza) war das größte faschistische Internierungslager in Italien, in Bezug sowohl auf seine Größe als auch auf die Anzahl der Internierten. Obwohl seine Existenz und die geschichtlichen Ereignisse, die es betrafen – d.h. seine Gründung vor dem italienischen Eintritt in den Zweiten Weltkrieg, seine Befreiung am 14. September 1943 bis zu seiner endgültigen Schließung im Jahr 1945 nach einer Zeit der britischen Verwaltung – ein fast vergessenes Kapitel der italienischen Geschichte sind, waren die musikalischen Aktivitäten, die dort stattfanden, umfangreich und erlauben eine Untersuchung ihrer Charakteristika und Funktionen. Gekennzeichnet durch die Anwesenheit von ausschließlich ausländischen Gefangenen, zumeist Juden, welche vor allem aus Deutschland stammten, oder aus Ländern unter Nazi-Besatzung (insbesondere Polen, Österreich, der Tschechoslowakei), aus dem Balkan (bedeutende Präsenz von Kroaten und Serben) und auch aus den italienischen Mittelmeer-besitzungen (Rhodos und Bengasi), diente Ferramonti als absurder und zufälliger Treffpunkt von Kulturen, Sprachen, Traditionen und Religionen in dem unzugänglichen, von Malaria heimgesuchten kalabrischen Hinterland. Unter den Gefangenen – oft mit einem sehr hohen Bildungsniveau – gab es mehrere professionelle Musiker, von denen einige schon internationale Karrieren in Angriff genommen hatten und andere in den folgenden Jahren nach dem Krieg beginnen würden, wie u.a. Lav Mirski, Kurt Sonnenfeld, Isak Thaler, Paul Gorin, Oscar Klein, Leon Levitch, Ladislav Sternberg usw. Darüber hinaus spiegelte sich die extreme kulturelle Vielfalt in der musikalischen Lager-Produktion wider. In ähnlicher Weise wie in vielen Nazi- Konzentrationslagern, entwickelte Ferramonti eine intensive musikalische Tätigkeit mit vielen Aspekten: Konzerte und Varieté-Programme; die Einrichtung eines Chores für Gottesdienste, der sowohl jüdische, als auch katholische und griechisch-orthodoxe Rituale begleitete (ein einzigartiges Beispiel nicht nur in der KZ-Musik); musikalische und allgemeine Ausbildung für Kinder und Jugendliche, die die Lager-Schule besuchten, um nur einige der auffälligsten Aspekte zu nennen.

Dieses Buch rekonstruiert auf Basis persönlicher und administrativer Quellen und Dokumente die musikalischen Praktiken und ihre Besonderheiten in einem »non-lieu« der Deportation wie Ferramonti. Dies geschieht durch die kritische Auseinandersetzung mit Sekundärliteratur, die Einordnung in historische Koordinaten und die ästhetische Problematisierung um die umstrittene Kategorie der „Lagermusik“. Somit werden solche Praktiken als Ausdruck kultureller ←21←|←22→Verhaltensweisen, die nicht nur die Grundlage einer lebendigen künstlerischen Produktion waren, sondern auch eine fundamentale Bedeutung für das Überleben der Insassen und die Wahrung individueller und kollektiver Identitäten hatten.

Abstract

Ferramonti di Tarsia (CS) fu il maggior campo di internamento fascista realizzato in Italia, sia per estensione che per numero di internati. Se la sua stessa esistenza e le vicende che lo interessarono – dalla fondazione all’indomani dell’ingresso nel secondo conflitto mondiale, alla sua liberazione, il 14 settembre 1943, alla sua definitiva chiusura nel 1945 dopo un periodo di gestione britannica – rappresentano un capitolo pressoché dimenticato della storia italiana, non meno importanti furono le attività musicali che si svolsero al suo interno. Caratterizzato dalla presenza di prigionieri quasi esclusivamente stranieri, per lo più ebrei, provenienti in larga parte dalla Germania, da paesi sotto l’occupazione nazista (Polonia, Austria, Cecoslovacchia), dai Balcani (significativa la presenza di croati e serbi) o deportati da possedimenti italiani nel Mediterraneo (Rodi e Bengasi), Ferramonti costituì un assurdo e aleatorio punto d’incontro di culture, lingue, tradizioni e religioni nell’impervio e malarico entroterra calabrese. Tra i prigionieri – sovente dotati di un livello di istruzione molto alto – si trovavano diversi musicisti di professione, alcuni dei quali avevano già intrapreso carriere internazionali o vi sarebbero stati destinati negli anni successivi alla guerra: Lav Mirski, Kurt Sonnenfeld, Isak Thaler, Paul Gorin, Oscar Klein, Leon Levitch, Ladislav Sternberg, et al. D’altronde, specchio dell’estrema varietà culturale fu proprio la produzione musicale che caratterizzò il campo. Similmente e forse ancor più che in molti campi di concentramento nazisti, a Ferramonti si sviluppò un’intensa attività musicale dai molteplici volti: dai concerti veri e propri di cui sopravvivono i “programmi di sala”, all’istituzione di un coro per le funzioni religiose tanto di rito ebraico, quanto cattolico e greco-ortodosso (un unicum non solo nell’ambito della musica concentrazionaria), all’educazione musicale rivolta a bambini e giovani che frequentavano la scuola del campo, solo per citare alcuni degli aspetti più sorprendenti.

Attraverso la disamina critica della letteratura secondaria, l’inquadramento entro coordinate storiche e la problematizzazione estetica intorno alla controversa categoria della Lagermusik, il presente lavoro ricostruisce le pratiche musicali e le loro specificità in un non-luogo della deportazione come Ferramonti, a partire da fonti amministrative e documenti personali, interpretandole come manifestazione di comportamenti culturali che furono alla base non solo una vivace produzione artistica, ma soprattutto determinanti per la soppravvivenza degli internati e la conservazione di identità individuali e collettive.

List of Figures

Figure 4. The programme of the Charity Concert on November 9, 1943 – Courtesy of Prof. Mario Rende.

←25←|←26→Introduction

This volume stems from the doctoral project “Ferramonti vergessen wir nicht”. Historical and Aesthetical Perspectives on Music in a Fascist Internment Camp (1940–45), conducted between November 2014 and March 2018 under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Cesare Fertonani and Inga Mai Groote as a cotutelle-de-thèse Ph.D. in Literature, Arts and Environmental Heritage and in Musicology in the Department of Cultural and Environmental Heritage at the University of Milan and Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar at Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg respectively.

My approach to the investigation in this volume, the methodology and the overall plan of the work reflect this origin: in particular, my primary interest has been the nature and features of musical practices in concentration camps and, more generally, the interpretation of these practices as cultural behaviors. Today the presence of music in certain fascist, Nazi and Soviet concentration camps seems to be well documented and the reconstruction of everyday life in these places – including cultural practices – is, in some cases, extremely accurate. These studies, however, are far from covering the whole spectrum of camps. The Italian case study examined in this volume is symptomatic of the oblivion (or sometimes negligence) that characterizes the investigation of civil internment in our country during the fascist era. Fascist internment camps, particularly in Central and Southern Italy, in the period 1940–1943 may be numerically less significant and may generally have had fewer dramatic consequences than other concentration camps; however, most of the history of these camps has yet to be written. The specific case of Ferramonti, which was first the subject of historical studies in the 1980s (Carlo S. Capogreco, Francesco Folino), has recently been studied from a musicological perspective. Raffaele Deluca’s Tradotti agli estremi confini. Musicisti ebrei internati in Italia (2019), in particular, proposes the reconstruction of the biographical experiences of certain prominent musicians interned in Ferramonti camp and their – in some cases very successful – careers in the decades after the war. This careful study, which is primarily based on extensive documentation in the Sonnenfeld-Schwarz Archive, cataloged by Deluca, and the private Locatelli Collection, affords fascinating glimpses of the potential of interned musicians in the camp and how the experience of internment influenced their respective artistic and human destinies in different ways.

Details

- Pages

- 230

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631863534

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631863541

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631863558

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631857335

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18769

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (August)

- Keywords

- Lagermusik Fascist camps Persecuted music Jewish musicians Holocaust music Interned musicians DP-camp music Lageralltag Holocaust representations Shoah music

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 230 pp., 10 fig. b/w.