Placing Poland at the heart of Irishness

Irish political elites in relation to Poland and the Poles in the first half of the nineteenth century

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- 1 From the Polish Partitions to the November Uprising, 1772–1830

- 1.1 Poland and Ireland in the End of Eighteenth and Beginning of the Nineteenth Century

- 1.2 Tribunes and Dynamics of Irish Interest in Polish Affairs

- 1.3 Main Points of Interest

- 1.3.1 Three Partitions of Poland (1772–1795)

- 1.3.2 The Napoleonic Era

- 1.3.3 The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) and the Kingdom of Poland

- Conclusion

- 2 The November Uprising: the Significance of the Polish Struggle

- 2.1 The Uprising

- 2.1.1 International Dimension

- 2.1.2 Internal Developments

- 2.2 Statistics and Geography of the Irish Reaction to the November Uprising

- 2.3 The Irish Knowledge of, and Attitude towards, the Polish Revolution

- Conclusion

- 3 The Irish in Relation to Poland and the Poles, 1832–1849

- 3.1 Poland and Ireland in the 1830s and 1840s

- 3.1.1 Poland after the Collapse of the Uprising

- 3.1.2 Ireland since Catholic Emancipation

- 3.2 Information and Comments

- 3.3 Politics

- 3.4 Charity, Culture and Other Platforms of Engagement

- Conclusion

- 4 Poland in the Context of Irish Political Affairs, 1831–1849

- Conclusion

- Epilogue

- Annex 1 Selected Letters and Documents Concerning Different Aspects of Irish-Polish Relations

- Annex 2 Poetry, Songs, and Other Literary Texts Regarding Poland Published in the Irish Newspapers between 1831 and 1849

- List of Figures

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

1 From the Polish Partitions to the November Uprising, 1772–1830

1.1 Poland and Ireland in the End of Eighteenth and Beginning of the Nineteenth Century

From the end of the eighteenth century until the 1830s, Ireland and Poland experienced profound historical changes. There were times of great hope, as well as dramatic events. In Ireland, for instance, the American Declaration of Independence (1776) provided the opportunity for seeking independence from Britain, which soon found its realisation in the ‘Grattan’s Parliament’ (the period of Irish legislative independence lasting from 1782 to the Act of Union of 1800). In Poland, the contemporary optimism may refer to the important reforms which were carried out by the Great Sejm (Polish Parliament), also known as the Four-Year Sejm (1788–1792). These hopes, however, were illusory. The Irish Parliament, for example, was not a fully representative body (it excluded most of the population – Irish Catholics) and did not have executive independence. The Polish reforms of the Four-Year Sejm, in particular the constitution of 3 May 1791, instead of producing the projected improvements, appeared to be just another argument for the Second Partition of Poland. Finally, both Ireland and Poland had lost their independence by the end of the eighteenth century: Ireland as a result of the Act of Union (1800) and Poland, in consequence of the Third Partition, in 1795.

Before the turn of the century, at a time when Poland experienced the most tragic destruction and hostility from the partitioning powers, the period known as the Protestant Ascendency prevailed in Ireland. After the Williamite War, which ended with the Treaty of Limerick (1691), guaranteeing religious freedom to Irish Catholics, the Protestant-controlled Irish Parliament introduced a series of laws directed against Catholics known as the Penal Laws.24 These laws reflected the insecurity of the Protestant minority in Ireland and simultaneously ‘reduced the Roman Catholic majority to a position of political, social, and economic inferiority’.25 Furthermore, Catholics were denied the right to buy land, to vote or take ←21 | 22→a seat in the parliament, to hold commissions in the army and navy, to practise law, or to maintain schools. Furthermore, those assuming offices and professions were required to take strongly anti-Catholic oaths. Most of these laws, however, were not strictly obeyed; nonetheless, as a result of the strengthening Protestant influence, the land owned by Catholics diminished, reaching 5 % by 1778.26 It is also estimated that just over 5,000 Catholics converted to Protestantism, ‘at least technically’, being motivated by legal relief, social status, or political participation. These were strategic conversions, often formed by ‘a sort of Catholic lobby’, along with converted lawyers and other professionals.27 In terms of education, which was available through a network of colleges in Spain, Portugal, France (which had the greatest number of students), Italy and the Netherlands, it worth noting that there was also a network of informal secondary schools in Ireland run by the clergy and laity, despite the penal restrictions.28

The Penal Laws, therefore, should be understood in terms of maintaining the balance between Protestant security – as Protestant interest was based on the possession of confiscated land during the previous land settlements (Cromwellian and Williamite) – and economic dependency – as Protestant landowners relied on Catholic labour, tenants, and cottiers to work on their vast estates.29 These laws helped to secure the Protestant Ascendancy in terms of its supreme position, secured the Church of Ireland, while denying the Catholics their political rights and limiting their land ownership. Protestant Dissenters were also excluded from political power, although they were not subject to Penal Laws. Moreover, in this environment a very sophisticated Protestant Irish (or Anglo-Irish) elite was formed and prospered – alongside the poverty that characterised the Irish countryside – that included Edmund Burke, Henry Grattan, and Jonathan Swift, who were often strenuous critics of the governance of Ireland. After the catastrophic famine of 1740–1741, known as the year of the slaughter, or the ‘Great ←22 | 23→Frost’ Famine, when mortality rates reached between 250,000 and 400,00030, the economic situation of Ireland gradually improved. However, this was confined to a few prosperous centres of Ireland and did not affect the majority of the rural inhabitants, which, in turn, led to agrarian protest (the Whiteboys, or Oakboys, etc.).

During this period the situation in Poland was very different but also involved dramatic and dynamic changes. It is important to remember that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was created as a result of a union with Lithuania.31 Before the First Partition (1772), this commonwealth covered a territory of over 730,000 sq. km, with a population of approximately 12 million. Of this, 60 % were Poles (40 % after 1772), 25 % were Ruthenians and Lithuanians, around 10 % were Jews, with Germans, Armenians and Tatars comprising less than 10 %. In relation to the social stratum, the nobility (or gentry – szlachta) and clergy constituted about 10 %, burgesses of the towns accounted for 20 %, and peasants around 70 %.32

In terms of politics, in 1732, a secret treaty between Russia, Austria and Prussia had already been signed. This agreement, known as the Treaty of the Three Black Eagles, was planned for Augustus III, Elector of Saxony, to succeed to the Polish throne, despite the fact that the majority of the Polish gentry (szlachta) supported the candidacy of a Pole, Stanisław Leszczyński. However, Poland in the eighteenth century had become increasingly under the influence of the above-mentioned foreign powers.

In Ireland, the Irish Protestants – including a group known as the Patriots, formed within the Irish Parliament and led by the lawyer Henry Grattan – began to seek an independent parliament under the Crown of Britain. The American War of Independence also influenced and inspired the Irish, giving them the opportunity to voice their demands. The British troops were withdrawn from Ireland, many being sent to America. In 1778, the Irish Parliament, led by ←23 | 24→Grattan to defend the country against a possible invasion by France, received the right to raise a Protestant militia – the Irish Volunteers – which was supported by Presbyterians and many middle-class Catholics. This became a recognisable national movement as the number rapidly grew, reaching 40,000 in September 1779.33 In February 1782, delegates of the Volunteers met at Dungannon, Co. Tyrone, where they demanded legislative independence for Ireland.34 The British Government, now in a very difficult position, without substantial forces in Ireland, had to face the Irish demands. As early as 1779, free trade with Ireland commenced, and restrictions on wool and glass were lifted. The two leaders Henry Grattan and Henry Flood then managed to achieve independent legislation for Ireland – the Irish Parliament (1782).35 Subsequently, most of the Penal Laws were abolished. Catholics were even permitted to serve in the British Army and in 1793 they were allowed to vote in parliamentary elections. The far-reaching concessions to Irish Catholics in 1793 became urgent as a result of the revolutionary events in France, which then offered support to ‘nations wishing to be free’.36 In 1795, a Catholic seminary, St Patrick’s College, was founded in Maynooth. However, Catholics still could not become members of the parliament, and this was despite Henry Grattan’s unsuccessful attempt to change this law in 1795.

About this time, in Poland, before the next election (Augustus III died in 1763), the situation had changed considerably. The Seven Years’ War (1757–1763) disunited the later partitioning powers of Poland, but the death of Tsarina Elisabeth (1762) brought about further changes. Peter III became Emperor of ←24 | 25→Russia for a very short time but was removed in 1762 as a result of coup d’état. From that point until 1796, Tsarina Catherine II (also known as Catherine the Great), ruled Russia. Now cooperating with Prussia, she had a growing interest in taking control of Poland; and Prussia was especially interested in unifying her Duchy of Prussia with Brandenburg. This meant annexing the Polish territories between them, to include the port city of Gdansk.

Poland at the time had been experiencing political struggles among the powerful parties associated with the influential magnates (the most powerful nobles) and their families (such as the Potockis and the Czartoryskis), and this was in conjunction with the rapidly deteriorating general situation of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. While Russia, Prussia and Austria were increasingly centralised and growing in strength, Poland was becoming weaker: the authority of a king and the Sejm (Polish Parliament) became practically insignificant and contrary to the increasing power of magnates, who were eager to the serve Russian and Prussian monarchs. The magnates managed to paralyse the Sejm by using the liberum veto (giving any deputy the right to break up a parliamentary debate), and in this way the Sejms were annulled – frequently by the bribery of foreign powers.37 Any attempt at a reform that would improve the status quo was perceived by the nobles as something what would awaken absolutism, and was an attack on their freedom, known as the Golden Freedom or the Nobles’ Democracy, with liberum veto at its centre. This attitude is understandable in light of the urgent need for peace after years of war.38 Nevertheless, the need for reform was pressing among certain powerful nobles: the Czartoryskis and Poniatowskis, known as ‘The Family’, proposed their programme for improvements to strengthen the central power of the State. However, they found strong opposition in the so-called republicans (or patriots) led by the Potockis.

Catherine II cooperated with ‘The Family’ during the pending election for the Polish throne, and despite the aspirations of the candidates, she announced her own candidate – Stanisław Poniatowski, a nephew of the heads of ‘The Family’. During his earlier visits in Petersburg, Poniatowski became romantically involved with the tsarina, and conducted a love affair with her.39 The election of the King ←25 | 26→of Poland took place on 6 September 1764. The Election Sejm, which consisting of 5,500 voters (gentry), and which was opened by the end of August 1764, voted in Stanisław Poniatowski. Voting took place with thousands of Catherine II’s Russian troops stationed nearby, along with the private army of ‘The Family’.40 The heads of opposition – Franciszek Salezy Potocki, Karol Radziwiłł and Jan Klemens Branicki – and the associated gentry did not participate in the election and were very hostile to the new Polish king. Although King Stanisław Augustus Poniatowski, one of the most talented Polish monarchs, received his crown thanks to Russia, he focused on reforms and the far-reaching independence of Poland, even when the country’s international position was becoming increasingly insignificant. Russia, on the other hand, was now concentrating on the political submission of Poland. In order to do this, the Russian minister in Warsaw, Prince Nicholas Repnin, took advantage of the intolerance expressed by the Polish gentry regarding non-Catholics in Poland (Protestants and Orthodox Christians): the Polish gentry strongly supported the dominant position of the Roman Catholic religion and refused to regard the other denominations as equals.

It is worth emphasising that from the end of sixteenth and during the seventeenth centuries the Roman Catholic religion (along with the Polish language) was becoming the major factor shaping and differentiating national individuality. However, the Counter-Reformation Catholicism was in opposition to the national liberation movements, and this did not change until the religious persecutions, especially in the Prussian and Russian partitions, that took place in the aftermath of the November Uprising (after 1830).41 For the Irish, the Catholic religion, from the end of the sixteenth century, would become ‘one conduit of anti-English feeling and eventually of national identity’.42 The Irish language was marginalised during the period 1730–1880 and by 1800 no longer played a major role in the Irish identity. It is assumed that at the start of the nineteenth century about 50 % of the population (2.5 million) spoke Irish, but many people were bilingual and used English as well as Irish. Equally, there were many English-speakers among the other half of the population who could speak or understand Irish.43

←26 | 27→In Poland, in 1767, two dissenter confederations were formed: in Słuck (Orthodox Christians) and in Torun (Protestants).44 A further confederation was formed in Radom (1767) under the leadership of Karol Radziwiłł, against King Stanisław Augustus. All confederations received Russian support in the name of religious rights, thus enabling Russia to gain control in the country. In the same year, a Confederate Sejm was opened with the presence of numerous Russian troops. During this Sejm, known as ‘Repnin Sejm’, the Polish opposition was brutally eliminated, and its leaders arrested and sent to Kaluga, in the depths of the Russian territory.

As a reaction to the Repnin Sejm, the Confederation of Bar (1768–1772) in Podolia took place in the name of religion (its defence), against Russia, and King Stanisław Augustus. The confederates fought against the Russians and some Polish troops but there was no single military or political command and the guerrilla war was chaotic. The critical point occurred when the confederates attempted to kidnap King Stanisław Augustus in 1771, an act which discredited the confederation in contemporary Europe. From then on, the undertaking died out. The Confederation of Bar ultimately ended in August 1772, along with the fall of Częstochowa.45 The four-year struggle ruined the country, which now additionally was occupied by thousands of Russian troops. At this time, Russia was hoping for the complete capitulation of Poland to its rule. However, the King of Prussia, Frederick II, managed to persuade the other two parties involved (Russia and Austria) to share this undertaking, and, in 1769, sent a proposal relating to the partitions of Poland to Russia. Ultimately, Russia, Prussia and Austria agreed to the concept of the partition. On 5 August 1772, the treaties were signed: Russia received 92,000 sq. km (the eastern territories of Lithuania and Belarus) along with 1.3 million inhabitants; Prussia received 36,000 sq. km (the north-west territories: Eastern Pomerania, but without Gdansk and Torun, ←27 | 28→and part of Wielkopolska, including Kuyavia), with 580,000 inhabitants; and Austria received 83,000 sq. km (the territories in the south from the rivers of Vistula and San, with Lvov and the salt mines of Wieliczka, excluding Cracow), with 2.6 million inhabitants. The territories taken by Austria were known as Galicia. As a result of the First Partition, Poland lost about 30 % of her territory and 37 % of the population, though of course, it was not confined to territories that were ethnically Polish.46

After the First Partition, Russia focused even more on the submission of Poland, but this was interrupted by the war with Turkey (1787–1792) and Sweden (1788–1790). Russia’s difficulties now gave Poland some space and opportunity for the real reforms.47 On that occasion, the permission to assemble a Confederate Sejm was granted (liberum veto suspended). This Sejm, known in Polish historiography as the Four-Year Sejm, operated from 1788 to 1792 and is considered to be one of the most significant events in Polish history. It was the time of serious debates and ideas involving political and social matters regarding the state of Poland. Furthermore, while the Sejm was working on an official draft of a constitution for Poland, King Stanisław decided to prepare a separate project (the British constitutional monarchy of which he had great knowledge became an inspiration for him).48 The deputies who now supported the king and reforms became known as the patriotic party. The constitution passed through the Sejm on 3 May 1791 and has since been known as the constitution of 3 May. This Act introduced constitutional monarchy in Poland. The king was at the head of the council (executive), which consisted of ministers – known as the Guardians of the Law – who were accountable to the Sejm. The Polish throne was to be hereditary through the Saxon dynasty. The term ‘nation’ encompassed more than just the gentry (naród szlachecki); liberum veto was abolished and peasants received protection under the law (however theoretical at that point).49 The constitution soon received the support of the Catholic Church, along with the Pope’s blessing.

←28 | 29→However, the Polish situation was rapidly becoming dangerous once again. Russia signed the peace agreement with Turkey in Jassy (January 1792) and began a military intervention in Poland. Simultaneously, the Field Marshal Grigory Potemkin contacted Stanisław Szczesny Potocki, Seweryn Rzewuski, and Ksawery Branicki – the staunch enemies of the constitution – who gave the pretext for the invasion. On 27 April 1792, along with other magnates, they signed the Act of Confederation at Petersburg, seeking the help of Russia against the revolution, which took place in Poland on 3 May 1791. Officially, the document of confederation was announced in Targowica,50 hence its name – the Confederation of Targowica. The Russian troops entered Poland at night on 18–19 May 1792, initiating the Polish-Russian War. Catherine II demanded that the Polish monarch reject the constitution of 3 May and join the Confederation of Targowica. Poland lost the war. Ultimately, King Stanisław Augustus agreed to the conditions, which at the time caused an outrage and led to his condemnation by many, including Tadeusz Kościuszko (who took part in the struggle after his return from America) and the king’s nephew, Prince Józef Poniatowski; both Kościuszko and Poniatowski resigned.

On 23 January 1793, the treaty was signed for the partition of Poland between Russia and Prussia. Austria, which did not participate at the time, was seeking Prussian consent for the incorporation of Bavaria. In consequence of the Second Partition, Prussia obtained 57,000 sq. km, including Gdansk and Torun, along with nearly 1 million inhabitants and Russia obtained 280,000 sq. km, with about 3 million inhabitants. As with the First Partition, the new annexations had to be confirmed by the Polish Sejm. However, the atmosphere in the country was becoming tense and again anti-Russian, which was strengthened by the brutal occupation of the foreign troops. In these circumstances, preparations for a new uprising were taking place. In Cracow, on 24 March 1794, the Commander-in-Chief Tadeusz Kościuszko proclaimed the Act of Insurrection, known also as the Kościuszko Insurrection (24 March-16 November 1794). The reasons for the uprising were highlighted in the Act of Insurrection and involved the liberation of Poland from the occupying forces, the security of her borders, the removal of any oppression within the country, or from abroad, and the strengthening of the national independence of Poland.51 During the insurrection, the commander-in-chief announced a decree at Połaniec (7 May 1794), whose main goal was to engage the peasants in the national struggle, however unsuccessfully. In ←29 | 30→accordance with the decree, peasants were to obtain personal freedom and security of tenure, and labour dues were to be significantly reduced. The Catholic Church, albeit divided in its support of the insurrection, helped to propagate the decree. Kościuszko, benefiting from his American experience, desired to engage Polish peasants in the national struggle, which accounted for the majority of the inhabitants of Poland. At the same time, he did not want to discourage the Polish gentry from taking part in the insurrection.52

In May, however, the Russian Army was backed by the Prussian troops, as Prussia decided to join the struggle against the Polish Insurrection. On 10 October 1794, about 80 km south-east of Warsaw, the Battle of Maciejowice took place. The considerably greater Russian forces under the command of General Ivan Fersen destroyed the Polish troops. The wounded Commander-in-Chief Kościuszko was taken prisoner along with his general staff. Now, General Alexander Suvorov turned to Warsaw and on 4 November captured Praga (a district of Warsaw), where he massacred the civilian population. Warsaw surrendered. Many insurgents were taken prisoner and many emigrated. The fate of Poland was ultimately lost. The three partitioning powers (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) decided to divide the remaining territory of Poland among themselves. The final treaties were signed: the Russian-Austrian treaty from December 1794-January 1795 and the Russian-Prussian treaty in October 1795. As a result, Prussia, in return for ceding Cracow to Austria, received Warsaw and the territories up to the Neman river in the east. The rivers Pilica, Vistula and Bug in the central part of the former Poland marked the borders between the three powers.

The 1790s were also particularly turbulent in Ireland, culminating in the Irish Rebellion of 1798. Ireland’s contribution in the battle against revolutionary France nearly made her bankrupt in 1797. The number of Irish recruits sent from Ireland during that period, including the Napoleonic Wars, reached about 150,000.53 The situation in Ireland itself was also becoming very tense – the provisions for the armed forces were enormous and especially severe for the general Irish population during periods of poor harvest. This, in turn, transformed into conflict that spread into the countryside. Violent agrarian secret societies such as the Catholic Defenders and Protestant Peep O’Day Boys (changed into the Orange Society in 1795) were in bloody conflict.

←30 | 31→In 1791, the Society of the United Irishmen was established in Belfast – then in Dublin – as a middle-class club. Among the leaders, who were mostly Presbyterian and from the Church of Ireland, were Theobald Wolfe Tone (1763–1798) and Arthur O’Connor (1763–1852). The United Irishmen were inspired by the French Revolution; they were dedicated to achieving parliamentary reform and Catholic emancipation. As a mass-based movement, the Society becomes a secret revolutionary organisation aiming to establish a non-sectarian republic in Ireland.54 The United Irishmen were – as emphasised by Nancy J. Curtin – ‘republicans in spirit’, and they would hope to implement their programme through peaceful reforms, but when these reforms were impossible they became ‘republicans in practice’. Therefore, they recruited reformers and revolutionaries.55 They desired a union of all the Irish, whatever their denomination, who could together remove the English control over Ireland, as outlined in Wolfe Tone’s pamphlet, An argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland (1791).56 After 1794, the United Irishmen, formed from middle class, radical artisans and tradesmen, peasants, and Catholic agrarian rebels (the Defenders), had managed to present considerable force. As soon as they joined forces with the Catholic Defenders, the revolutionary tone dominated in the Society; and with the support of the Defenders, ‘the United Irish movement became a national one’.57 The United Irishmen voiced their views through the Northern Star. In 1794, after a collaboration with the French Government was discovered by the government, the Society was suppressed. Tone, as a result of an agreement with the authorities, left Ireland for America and subsequently moved to France, where he tried to persuade the French to support the Irish in their revolutionary struggle, which, as he confirmed, was on the brink of a breakout. However, this was far from reality.

←31 | 32→The French, who were convinced by Wolfe Tone, decided to send a fleet along with 14,000 French troops to Ireland. The stormy weather thwarted the undertaking, preventing the troops from landing at the Irish coast, and soon the fleet had to return to France. In 1796, the Insurrection Act was introduced to suppress a revolutionary movement, and habeas corpus was suspended. An extremely brutal and bloody campaign commenced. However, it did not prevent the rebellion from breaking out. In May 1798, about 30,000 volunteers rose up in Counties Wexford and Wicklow, and, after capturing the city of Wexford, they proclaimed the Irish Republic. Shortly thereafter, the rebels massacred a number of loyalists and Protestants in Scullabogue, County Wexford; the sectarian conflict, as mentioned above, sometimes extremely brutal, had also been present for many years in south Ulster. The struggle soon found its bloody culmination at the Battle of Vinegar Hill. The British forces, led by General Gerard Lake, slaughtered the Irish rebels at the battlefield without difficulty. The French once again reached out in support of the Irish. In August 1798, they landed in Killala, County Mayo, but realising that revolutionary Ireland, as described by Wolfe Tone, was in fact not so revolutionary, they decided to retreat. Wolfe Tone was arrested not long afterwards. He was imprisoned with other leaders of the United Irishmen and convicted of treason. However, he died by suicide (November 1798) and is now considered as the father of modern Irish republicanism. It is estimated that the Rebellion of 1798 (May-September) totalled around 30,000 deaths.58

Despite the tragic outcome of the Rebellion of 1798, the new group of radicals appeared and began to prepare for a new uprising. The leader of the anticipated revolution was Robert Emmet (United Irishman). However, the planned revolution failed. Emmet was arrested, charged with high treason, and executed. It is important to bear in mind the fact that the leaders of both events (Wolfe Tone, 1798) and Robert Emmet (1803) occupy a particularly important place in modern Irish revolutionary nationalism.

In Poland, after the Kościuszko Insurrection, the Poles were unable to adopt a common view regarding the reinstatement of Poland. Some believed that it should be done by taking up arms again, while others that it would be possible to achieve alongside the international situation, which would break the alliance between the three partitioning powers. However, new circumstances had begun to emerge with the growing power of Napoleon I, who soon undermined the status quo in Europe. Many Poles who emigrated (mainly to France), but also those who remained in the country (e.g. the members of the secret Society of ←32 | 33→Polish Republicans established in Warsaw, in 1798)59 were convinced that the opportunity to regain Poland had arrived. Franciszek Barss and Józef Wybicki met with Napoleon I and presented the idea of a Polish Legion that would be formed alongside the French Army. Napoleon agreed, and the Polish Legion was created in Lombardy under the command of General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski. In 1799, another Polish Legion was formed which was assigned to General Karol Kniaziewicz. It is important to bear in mind the fact that although Napoleon I officially condemned the partitions of Poland and promised his support for the Poles, he was very instrumental in his approach, taking advantage of the sensitivity involving the Polish Question for Russia, Prussia and Austria.60

Napoleon I turned towards the Poles after his victories at Austerlitz in December 1805 and, then, at Jena and Auerstädt in October 1806. He again seized the opportunity to take advantage of the Polish support – making the appeal a promise of independence, but nothing concrete – during his campaign against Prussia. The support of the Poles in the Prussian partition against the Russian army appeared crucial.61 However, at the time, there was another idea of the restoration of Poland under Tsar Alexander, advocated by Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, Acting Minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia (1804–1806). From November 1809 to April 1810, Czartoryski had frequently dined with Tsar Alexander, who envisaged some kind of autonomy for the kingdom (Czartoryski, on the other hand, insisted on the constitution of 3 May 1791) and expected that the Poles would turn against Napoleon.62 However, this plan was ultimately unsuccessful.

In November 1806, General Dąbrowski and Józef Wybicki issued a revolutionary appeal63 that soon found its response in the Polish Uprising. A provisional ←33 | 34→Polish administration was organised along with about 32,000 (in 1809) Polish troops, divided into three legions under the command of General Dąbrowski, General Józef Zajaczek, and Prince Józef Poniatowski (King Stanisław Augustus’ nephew). These troops were engaged in skirmishes against the Prussian forces in Pomerania and Silesia.64

After the victory of Napoleon I over the Russians at Friedland (June 1807), in the course of secret talks in Tilsit, a compromise was worked out and the Duchy of Warsaw was created as a French outpost. The King of Saxony, Frederick August, ‘the most ardent vassal’ of Napoleon, was appointed to rule in the Duchy.65 The territory of the Duchy of Warsaw, based on the treaties signed in Tilsit (7 July 1807), was created from the Prussian partition of Poland (the Second and Third Partition), and comprised 103,000 sq. km, with a population around 2.5 million. Prussia lost half its territory and Gdansk became a free city.66 In 1809, the Duchy was enlarged by four districts taken from Austria, which had lost another war with Napoleon. Prince Józef Poniatowski, who commanded the army of the Duchy of Warsaw, fought against much greater Austrian troops at the Battle of Raszyn (19 April 1809) and managed to gain a victory.

In 1807, the Duchy received its constitution from the French Emperor, which abolished serfdom and proclaimed the equality of all citizens before the law. The Napoleonic Code was also subsequently introduced. After initial difficulties, the Duchy of Warsaw was well organised, providing Napoleon with a high standard of soldiers, whose skills were proved in many military campaigns.

However, there were greater hopes among the Poles regarding Napoleon’s victory over Russia. Just before the Russian campaign, the Polish Army in the Duchy was increased to 100,000 soldiers. On his way to Russia, the emperor gave orders that the Sejm needed to be convened, and during its session a proclamation regarding the reinstatement of the Kingdom of Poland was issued. However, this anticipated undertaking was lost along with Napoleon’s catastrophe in Russia, which also nearly destroyed the Polish Army that accompanied him. Pursuing the French forces, the Russian Army entered the Duchy of Warsaw in January ←34 | 35→1813, once again initiating the scheme for uniting Polish territory under the Russian ruler. This was soon decided at the Congress of Vienna.

From autumn 1814, the representatives of the anti-Napoleon coalition began to arrive in Vienna to establish a new order in Europe. Despite the attendance of numerous countries present at the congress, the actual decisions were made primarily by Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and France.67 The main sides during the talks were Russia and Prussia – with Emperor Alexander I of Russia, whose country made the greatest contribution in the defeat of Napoleon I – and Britain, Austria, and France, working together to prevent the domination of Russia and Prussia in Europe. The Duchy of Warsaw and Saxony – the latter Tsar envisaged as being annexed by Prussia in order to fulfil her territorial demands, and for punishing Frederick Augustus for his support for Napoleon I – became the core of difficult disputes, causing major friction between powers.68 Tsar Alexander I insisted on taking over the Duchy of Warsaw in order to establish an autonomous Kingdom of Poland in union with Russia. The Emperor of Russia promised to implement a liberal constitution and reunite the newly created kingdom with the former eastern territories of Poland. However, the British stance in respect to Poland presented an alternative for Russia: the full restoration of the Kingdom of Poland, or the division of the Duchy of Warsaw.69 Ultimately, Russia received two-thirds of the Duchy of Warsaw from which an autonomous (but not sovereign) Kingdom of Poland, also known as Congress Poland, was established. The western departments of the Duchy of Warsaw were transformed into the Grand Duchy of Posen and, along with Gdansk, were given to Prussia. Austria received Galicia and Wieliczka, and the Republic of Cracow was formed from the territory of Cracow, remaining under the control – through residents seated in Cracow – of Russia, Prussia and Austria.70

In Ireland, the Rebellion of 1798 shocked the British Government. It was assumed that security for the empire and peace for Ireland could be achieved only by the abolition of the Irish Parliament and by creating a United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland, with one parliament at Westminster. For Prime Minister William Pitt, the union was to counteract the ‘machinations’ of France, and the way to achieve this was to calm the issues of Ireland, which Catholic emancipation ←35 | 36→constituted part of the objective “for placing ‘under one public will the directions of the whole force of the empire’ ”.71 The distribution of Crown patronage and bribery, and ‘every attempt’ was made to persuade MPs to support the union, which was formally created on 1 January 1801.72 It is worth noting that up until this point Catholics in Ireland were in proportion to Protestants as three to one, while in the United Kingdom they were three to eleven.73 Nevertheless, initially many Protestants opposed the union with Britain, criticised it for constitutional and commercial reasons, and believed that it would lead to Catholic emancipation. However, they were soon convinced that the union actually provided them with security of their property and religion.74 From a different perspective, Irish nationalists considered the act of union as an ‘act of power and corruption’, as expressed by the son of Henry Grattan.75 Nevertheless, the Irish Catholics, despite their conviction that the union would bring full emancipation, quickly realised that this was not the case. When most of the restrictions for Catholics had been abolished by 1793, they still could not take a seat in parliament – notwithstanding an attempt to change this law by the newly appointed Lord Lieutenant, Earl Fitzwilliam, in 1795 – or hold the highest offices, as well as ranks in the army. The union was to be a Protestant union, as there was soon a belief that Catholic emancipation was just a continuation of the republican conspiracy of the 1790s and a vehicle for Irish separatism and Catholic ascendency.76 After the defeat of Napoleon I, the situation in Ireland was still unstable and manifested itself in the number of 33,000 soldiers who were kept in the country. Therefore, without a choice, being discriminated against, the Irish Catholics continue their struggle for emancipation. On the other hand, as this should be underlined, the union at the same time brought Ireland and her relationship with England into the centre of the British political system.77 However, it did not change the fact ←36 | 37→that there were ‘striking differences’ between the two countries, in terms of historic tradition, economic development, denominal balance, and social pattern.78

Notwithstanding strong opposition, the successive bills regarding Catholic emancipation were introduced in the House of Commons in 1821 and 1825 but, in spite of passing the Lower House, they were lost in the House of Lords. It was not until 1823 that the system was challenged by Daniel O’Connell, ‘the champion of Irish Catholic nationalism’,79 who established the Catholic Association. He believed in ‘moral force’ as a vital instrument in achieving emancipation: his constitutional politics had the momentum of opportunity as the bloody Rebellion of 1798 was still remembered, and never to be repeated again.80 This Association, accompanied by the Catholic Church, quickly became a very powerful instrument of mass mobilisation and presented the new tactics employed by O’Connell, who wanted a movement built from the bottom up; no longer financed by a middle-class elite, ‘patronised’ by a Catholic aristocracy, and reliant on supporters in the parliament. Catholics had to prove that they ‘deserved to be free’.81 It is also worth remembering that O’Connell’s movement was the first modern political structure in Europe, ‘an unprecedented organisation of democratic power’.82 The cost of membership, the so-called Catholic rent, was affordable even for the poor Irish, and in return the Association had considerable funds at its disposal, as well as the support for pro-emancipation election candidates. After a few years, the results of the Catholic emancipation campaign were clear: in 1828, Daniel O’Connell won a by-election in County Clare (even though, as a Catholic, he would not be able to take a seat) against C.E. Vesey Fitzgerald. O’Connell’s victory not only challenged the Protestant Ascendency but also the traditional control over county politics. It also illustrated the power of the Association managed by middle-class liberal politicians.83

Now, supported by the Church and the Irish masses, O’Connell managed to enforce the legal changes on the British Government led by Arthur Wellesley ←37 | 38→(born in Ireland), the Duke of Wellington. Threatened by a civil war, but also realising that there was a growing support for the emancipation within the parliament, Wellington and Robert Peel (Home Secretary) introduced a bill for Catholic emancipation. Passing both Houses of Parliament, the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829 became law on 13 April 1829.

In Poland, after the year 1815, many Poles were engaged with conspiracies, especially representatives of the intelligentsia, students and officers in the army (nearly all of impoverished gentry origin) and began to form secret associations. Freemasonry played an important role here and despite its moderate liberal programme, lodges masked the activities of more revolutionary agendas supported by radical members.84 This was also the case in Ireland, although before the end of the eighteenth century. Many conspirators were linked with the Carbonari, an organisation seeking democratisation and independence, but soon these conspiracies were uncovered by the authorities and the Russian secret police. The Russian senator Nikolai Novosiltzow was especially effective in this respect and was sent to Vilnius in order to investigate the underground activities. The situation in the Kingdom of Poland, however, had changed dramatically with the outbreak of the November Uprising. The Polish Revolution opened a new chapter in Polish history. Although it was a time of severe repercussions and suffering experienced by many Poles, this revolution initiated another stage of struggle for the national cause, which also had an Irish dimension.

1.2 Tribunes and Dynamics of Irish Interest in Polish Affairs

Even if the numerous analogies and mutual sympathies – expressed to a much greater degree by the Irish than the Poles – can be found within the entire period (1772–1830), it was not until the 1830s and 1840s that they had become fully comprehended and exploited for political reasons. Therefore, if the 58 years examined here represent the longest time span, it should be stressed that the Irish interests in Polish affairs (or expressed attitudes towards Poland) manifested themselves mostly during the crucial moments for Poland.

The Polish events that were observed and reported by the Irish (among others) focused on the following: the successive partitions, the constitution of 3 May, the Insurrection of 1794, the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw, the participation of the Poles in Napoleon I’s Russian campaign, and the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland at the Congress of Vienna (see Figs 1 and 2 below). However, ←38 | 39→despite the fact that Poland was observed closely at times, she was rather distant, or even exotic to a certain extent.

Although this study refers to numerous and varied sources, the main indicator of the Irish interest in Polish matters for the period 1772–1830, especially in terms of its general intensity, was based on the two newspapers issued at that time in Ireland, and like most of the writing material at this period (and beyond), was produced by members of the upper or middle classes.85 These were the ←39 | 40→Freeman’s Journal and Belfast News-Letter. The Belfast News-Letter was later considered to have ‘a formidable rival’ in the Freeman’s Journal.86 The latter, which was established in 1763 by Charles Lucas, supported Catholic emancipation and the repeal of the union with Britain. It was an anti-government and nationalist paper, issued for 161 years (until 1924). At an early stage, it was associated with patriot parliamentary opposition, and among its contributors were Henry Grattan and Henry Flood. The Belfast News-Letter – established in 1737 by Francis Joy – was initially a patriot journal, supporting free trade and the repeal of Poynings’ Law.87 From 1795, under George Gordon ownership, it became a conservative and pro-government Protestant paper. In 1845, it was acquired by the owner of another Ulster newspaper – the Newry Telegraph. The Freeman’s Journal and Belfast News-Letter were the oldest daily newspapers in Ireland, and Britain for that matter.88

While the newspapers in Ireland began to take a more ‘regular shape’ (from the mid-1700s), they remained ‘an elite form of communication, aimed primarily at the English-speaking, Protestant population’.89 Nevertheless, at the time of political and economic change, Irish legislative independence, and the aspirations of the Irish Catholics, in the 1770s and 1780s, ‘the role of the newspaper as a medium for public debate, and of journalism as a means of keeping an eye on the doings of government, continued to evolve’. The same applied to the Government for controlling journalism: it conceded the right of printers to publish parliamentary ←40 | 41→debates (1771) and imposed a stamp duty on newspapers (1774). There was also a tax on advertising (1712), which was directed against opposition newspapers, as they did not benefit from patronage of the Government. Additionally, the authorities in Dublin Castle exercised favouritism in terms of the distribution of news – the London papers, critical in terms of content, were only distributed to newspapers ‘in favour with Dublin Castle’.90

The newspapers were ‘generally one-person operations’ but information came from many sources (e.g. political clubs, coffeehouses, the crews of the arriving ships). The vital source was in the form of newspapers arriving from London, from which a part or the whole paper was often copied.91 News involving Poland came largely from English newspapers – which also copied foreign papers; and the Irish counterparts often identified the source, for example ‘a letter from Warsaw’, ‘accounts received from the Continent by way of Silesia’, or ‘letters from Cracow’. In the period of intense interest during the Napoleonic era, newspapers often used published Bulletins of the Grand Army, and later, for instance, The Chronicle of the Congress of Vienna. Last but not least were the short, but very valuable, editor’s comments. The extensive variety of materials allowed the Irish to be well informed about contemporary Polish affairs; and if the authors of these reports, comments or articles were largely unknown – perhaps predominantly not even Irish – they still reflect the ‘Irish intellectual preoccupation’ by the agency of the editors’ decisions to include such pieces, in order to fulfil the ‘expectations’ of Irish readers, who would find them of interest.92

For the purpose of this study, the above-mentioned newspapers, as well as the digitally accessible Leinster Journal for the year 1772,93 were searched with reference to ‘Poland’, ‘Poles’, and ‘Polish’ affairs. Although these sources are not ←41 | 42→complete,94 they are the most representative and sufficient to establish, with certainty, the required trends of interest.

As can be seen from Fig. 1, the Irish interest focused on the main historical events that took place in Poland. Perhaps the most significant fact is that throughout the examined period, not a year that had passed without mentioning Poland. However, there were times when this preoccupation was very low, especially in the years 1777–1783, 1796–1805, and 1816–1822. On the other hand, the highest attention to Polish affairs was visible in the following periods: the year 1773 (just after the First Partition and regarding this event), from 1788–1795 (from the time of the Four-Year Sejm through the Insurrection of 1794 to the Third Partition of Poland), the year 1807 (predominantly focused on the struggle of Napoleon I in Polish territory, including the Poles as part of the French Army; and only secondary attention was directed to the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw). Crucially, from April 1806 onwards, the Freeman’s Journal increased its issues from three to six days a week (from Monday to Saturday), which strongly reflected in the number of references with regard to Poland. Napoleon I’s Russian campaign in 1812 (Poland and the Poles were mentioned in conjunction with the French effort against Russia) and the Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815 (concentrating on difficulties regarding Poland and the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland), were widely reported.

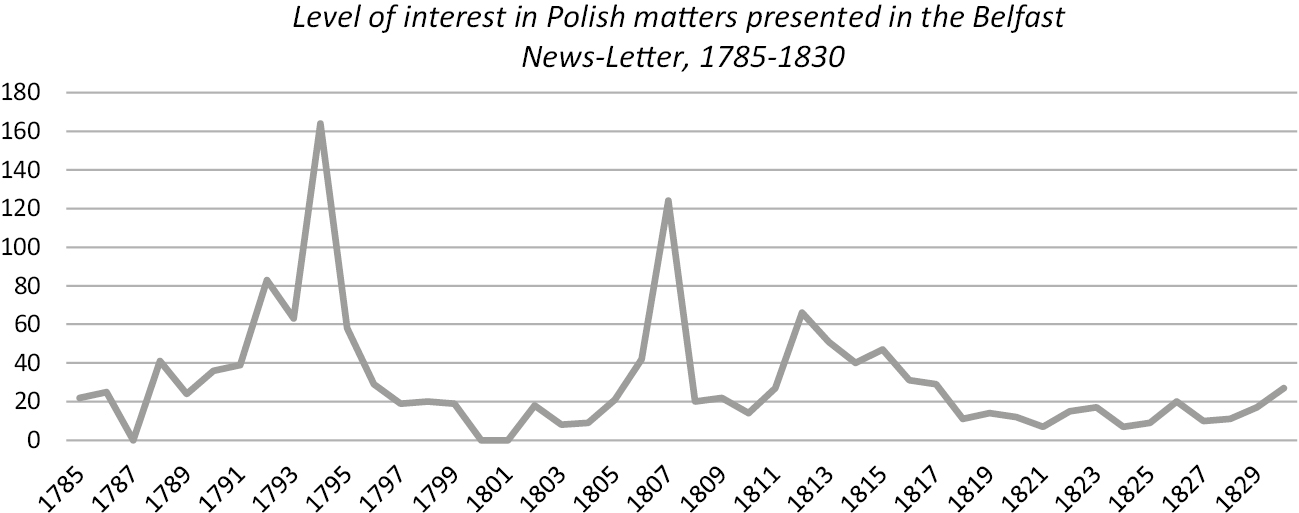

Figure 2 shows the level of interest in Polish matters presented in the Belfast News-Letter. It is important to bear in mind the fact that there were considerable discrepancies between the Freeman’s Journal and the Belfast News-Letter as far as Polish affairs were concerned. Nevertheless, the Belfast News-Letter also presented particular interest in the subject during the times of the main historical upheavals involving Poland. However, the period from the First Partition of Poland (1772) to the year 1785 is not included here, as these years were not accessible.95

←42 | 43→The graph above indicates that the editors of the Belfast News-Letter showed the highest interest in Polish matters, along with the ultimate fall of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Considerable attention was given to the activity of the Four-Year Sejm (1788–1792), the Insurrection of 1794, and the Third Partition of Poland (1795). Another peak of interest is observed in 1807, when the successes of Napoleon I in Central-Eastern Europe led to the creation of the Duchy of Warsaw. The editors of the Belfast News-Letter were interested in the newly established Duchy, as well as in Napoleon’s unsuccessful campaign in Russia, and the simultaneous collapse of the French domination in Europe. Attention was also paid to the Poles who fought by Napoleon’s side and to the Congress of Vienna itself.

Although the above graphs clearly indicate Ireland’s growing interest in Polish matters, each of these periods needs to be shown in more comprehensive and extensive detail.

Details

- Pages

- 352

- Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631824672

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631824689

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631824696

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631818176

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17065

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (June)

- Keywords

- November Uprising Diplomacy International relations Irish-Polish relations Polish Question Irish Question

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 352 pp., 8 fig. b/w.