Series co-editors Patrícia Vieira and Susan McHugh share their vision

With our new book series Plants and Animals: Interdisciplinary Approaches, we aim to grow connections between the emerging fields of critical plant studies and animal studies. Our editorial partnership represents a rare convergence of strengths in both areas, so we bring to the book series a keen sense of potentials for bridging them. In tandem with related fields like posthumanism and ecocriticism, the series is geared to enrich scientific knowledge by shining a spotlight on the connections across vegetal and animal life through studies grounded in the humanities. What can animal studies scholars learn from current plant research and vice versa? How do studies that encompass both plants and animals (and, potentially, other living and non-living forms of existence) enrich our understanding of our planet in all its diversity? Recognizing that a need for more equitable and harmonious forms of coexistence cuts across the most pressing social and environmental issues, Plants and Animals embraces both imaginative critique as well as creative problem solving in order to overcome obstacles to growing relations.

Until recently, plants and animals alike were studiously avoided as serious subjects for academic humanists. Worse, efforts to correct this mistake sometimes contributed to the further misperceptions of them as two mutually exclusive areas of interest for non-scientists. Critical plant studies, which has accelerated in the last decade, was initially posited as having been developed in opposition to the exponential growth in animal-centered research in the humanities since the end of the last century. Perceptions of the neglect of the vegetal in favour of the animate gained traction, particularly in studies that emphasized the western tradition. What is more, those seeking to define critical plant studies against animal studies scholarship characterized animal studies scholars as actively undermining interests in vegetal life. The heterogeneity of animal studies — a field variously known as human-animal studies, critical animal studies, or anthrozoology, and home to such diverse offshoots as vegan studies, literary animal studies, and cryptozoology — makes room for such criticisms. But the ever-growing multiplicity of voices espousing interests that bridge animal and plant studies also helps to erode claims that the barriers between them are insurmountable.

Intriguingly, few critical plant studies or animal studies researchers today appear to perceive each other as threats. If anything, the numbers of established animal studies scholars now also publishing in critical plant studies and vice versa are on the rise, meaning that any old sense of rivalry simply rings untrue. Instead, the disproportionately slow development of institutional support for humanistic studies of nonhuman life has emerged as one among many common causes, and a pressing reason for thinking that moves across academic silos, not to mention what/ why/ how different species converge in their literal referents. The stakes have never been higher.

Pushing traditional humanist thought beyond anthropocentrism, animal together with plant thinking is vital to solving the global problems of climate change and anthropogenic extinction. To support and develop the mutual growth of critical plant and animal studies, we want the series to publish scholarship that connects them more immediately, and ultimately to provide a framework that guides these nascent fields toward more purposeful interactions for years to come. The genuinely new knowledges that can emerge from crossover conversations need to be nurtured. Doing so entails not only dispelling the specters of schisms that may be holding back students and junior faculty from owning allegiances in both fields, but also providing them with encouragement to develop new pathways of research.

To be clear, we seek to learn from past mistakes, especially in order to create a robustly welcoming environment for equitable, inclusive, and diverse scholarship across plant and animal studies. It cannot be said often enough that the success of the “animal turn” in humanities and social sciences research can be credited to scholars reaching across disciplinary divides, particularly in the early days when nonhumans were considered scientific (again vs. humanistic) subjects. The strong feminist and queer-theoretical orientations of many early animal studies scholars had the significant benefit of rendering self-reflexive critique along the lines of feminist ecocriticism unnecessary. That said, the emergence only within the past few years of a robust body of animal studies scholarship that directly addresses the concerns of critical race and decolonial studies indicates how the field has been hampered in its inception by inattention to a broader range of social justice issues and contexts.

The over-representation of Anglophone and Euro-American scholars and projects is an ongoing issue in the academy, though one that the persistence of plants and animals across places and times can enable us to overcome. As editors, the global reach of our own different research networks — and those of our international editorial board — empowers our search for greater representation. The goal is a robust future for plant and animal studies research that will inspire action, ideally leading to meaningful socio-environmental changes for the benefit of all.

Critics should take note that the material history of writing alone makes the series a no-brainer. From ancient times, bark, bast, and vellum have been used as writing surfaces, inked in with ingredients like tree resin or gallnuts, animal bone or hide glue. Before the twentieth-century invention of synthetic adhesives, even books promoting animal rights contained remains of the proverbial horse sent to the glue factory. The detail in Nobel laureate Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (1987) that enslaved protagonist Sethe is tasked with making the gallnut ink used by her white tormentor Schoolteacher likewise serves as a subtle reminder that the modern proliferation of writing materials has deep roots in the plantations of settler colonialism. That such details are not — or not yet — common knowledge, however, gives pause to consider how justice for those written out of the human fold can be advanced only by taking plants and animals seriously.

Non-human beings, including plants and animals, exist, like humans, in tight communities, where mutual exchanges are ongoing. Humanistic knowledge should embrace these complexities and avoid artificial compartmentalizations of different forms of life. With Plants and Animals, we want to encourage the creation of scholarship that overcomes such boundaries, which exist nowhere but as relics of hackneyed thought. Among many other vital connections, plants need animals, such as insects, to reproduce, and animals need plants to breathe. What better example is there than symbiotic relationships to illustrate the kinds of scholarly exchanges we wish to foster with our series?

Learn more here. For further information, please contact Dr. Laurel Plapp, Senior Acquisitions Editor, at Peter Lang at l.plapp@peterlang.com

A (S)Mothering Inheritance in an Age of Precarity, or, We’re Too Removed from the World to Ever Be in It

This blog post will look at two films, Hereditary (2018) by Ari Aster and Incantation (2022) by Kevin Ko. On the surface they seem very different from each other, with Aster’s film being labelled as “elevated” horror, with a very thoughtful and aestheticized approach to set design, camera work and pacing, while Ko’s relies heavily on a found-footage aesthetic, frenetic action and continual jump scares. In many senses, they serve as examples of the opposing poles of recent horror, one concentrating on a more intellectual and artistic approach (Hereditary) and the other being very referential to the wider genre and often dependent on many sudden shocks and scares (Incantation).

However, while both share elements often attributed to the Folk Horror subgenre — plots involving non-majority religious cults and rural settings — this article will argue they share a far deeper connection through what we might call an “undead heritage” that is focused around a maternal figure. This can seen to be linked to the more well-known ideas of a family curse or “the sins of the fathers/mothers”, although strong male figures are largely absent in both films. This theme has very specific connotations in the twenty-first century that are strongly indicative of the “age of precarity” we are currently experiencing in the 2020s and our inability to protect our futures.

“Undead”, here, as more fully explored in The Undead in the 21st Century: A Companion, signifies an entity that is neither dead nor alive — even beyond life and death, in some way — and driven by an insatiable desire to consume, or find sustenance in, humanity. In both these films, this “undeadness” is manifested in a god-like, supernatural entity that is outside human conceptions of life and death — effectively immortal in most senses of the word — and which is compelled to draw the life from humanity,[1] and, more specifically, humans linked by family bonds, using a ritual of some kind (this often requires the recitation of a text that “invites” the undead entity “in” and consequently “curses” the recitee). Curses or undead language is of note in each film as the person being cursed does not need to know what they’re saying, but the performative nature of the recitation acts as an invitation to the undead entity.

This idea of unknowing is important for the undead heritage theme, as it often belies an inability of the present — as embodied in the victim — to understand the meaning of the past that is often in plain sight. The victims inevitably only understand the meaning of the “clues” of the past when it is too late and they are about to be consumed by their undead heritage (a common theme in Folk Horror). Indeed, unknowingness plays a large part in many forms of precarity, particularly in relation to contemporary ecological and political environments.

Before looking at the films more closely, it should be mentioned that the two narratives look at undead heritage slightly differently and, cultural specificity aside, also point to a slightly different view of the world in 2022 than in pre-pandemic 2018.

Hereditary features Annie (Toni Collette), who is grieving the recent death of her mother. Their relationship in life was extremely problematic, even abusive, and although Annie is surrounded by both physical and psychological memories of her mother’s past, she prefers to reconstruct the present to try to understand her increasing sense of foreboding. On top of this, her daughter, Charlie (Milly Shapiro) is decapitated in a freak accident involving Peter (Alex Wolff), her son and Charlie’s brother. Annie meets Joan (Ann Dowd) at a bereavement group and she admits to her she had “given” Charlie to her mother as a placatory measure, but it had left her even more excluded from both of their lives. Indeed, Annie appears deeply removed both from the feminine heritage of her own family (her mother and her daughter) and the world around her, and the lifelike models she makes are attempts to control and place herself in her environment.

Joan gets increasingly close to her and reveals that she has managed to contact the dead and can show Annie how to do it, too. Annie then performs the ritual as described to her by Joan, importantly reciting a verse of a language she doesn’t understand, and forcing her husband and son to do so with her. This effectively invites the demon king Paimon into the human world, allowing him to possess the body of her son and kill all those that are not supplicants to his power. It seems that Annie’s mother was a high priestess who had linked Paimon to the “soul” of Charlie, who should have been born a boy, and now wants to inhabit Peter. It is only at this point, once her undead heritage has overtaken her, that Annie realizes what is occurring and that the clues were all around her in her mother’s belongings: Joan is in her mother’s photos of occult rituals, and highlighted passages in her copies of esoteric books all point toward worship of Paimon and inviting him into the world through the body of a boy.[2]

It also gives further meaning to the distance from her own children and her subconscious attempts to kill them — in not killing them, she has effectively ended the world as we know it. Overwhelmed by her undead heritage and her inability to protect her family or herself, Annie loses her grip on reality, her identity and literally, her head, as Paimon possesses the body of Peter and becomes manifest. Exactly what Paimon intends is not made clear, though one suspects it will add to the precarity of a world already out of balance, though one that neither Annie or her family will be part of.

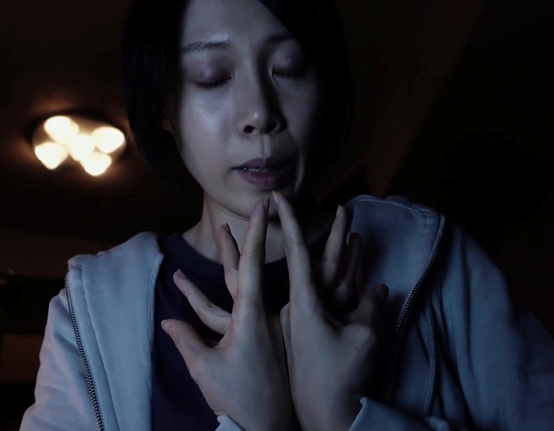

Incantation focuses on Ruo-nan (Hsuan-yen Tsai), whose life is a frantic pastiche of flashbacks and ragged camera footage as she tries to hold on to the present and envision a future for her young daughter. The curse she now carries is not her own but one that she stumbled upon, bringing the undead heritage of others into her own familial lineage. Some time ago, Ruo-nan and a group of “Ghostbuster” friends went to the ancestral village in rural Taiwan of one of their number. The villagers and the friend’s relations told them to leave as a special and potentially dangerous ritual was being performed, but the rebellious friends stayed, interrupting the ceremony and breaking into the shrine, despite all the warnings they were repeatedly given.

Not all the friends escape, as some unseen power overtakes them and Ruo-nan, who unbeknownst to herself was pregnant, was forced to recite a “blessing” while placing her hands in a special configuration. Deeply affected by the events, Ruo-nan gives up her child and only many years later feels strong enough to reclaim her from those caring for her. It is only at this point that her undead heritage begins to catch up with her and she soon realizes that it’s been passed on to her daughter. Now that the curse is starting to affect her life, she decides to investigate further to understand what she and her friends had done and pieces together what the past actually means for her daughter’s future.

The curse seems to take the form of ever-increasing precarity as Ruo-Nan’s actions become progressively frantic and her life spins out of her control.

It transpires that the village worshiped a malevolent deity and that the “blessing” — which takes the form of a multi-syllabic phrase — is in fact a curse, that when repeated invites it into your life and slowly kills you. Ruo-nan’s daughter, Dodo (Sin-ting Huang), even after following the advice of local religious healers, is getting increasingly worse, so she goes back to the village, the past, to undo the present. However, once there, she goes into the depths of the underground shrine to confront the image of the deity and realizes that once the curse, the undead heritage, has been invited in, it cannot be revoked but only lessened through sharing.

Ruo-nan then ends the film as it started, as she has done at various points throughout the narrative, inviting us the audience to recite the inverted blessing so that we might share the curse and lessen its affects on her daughter. Here, then, Ruo-nan’s gradual understanding of the undead heritage she has released mirrors our own, as we realize that the phrase we have been asked to recite has cursed us: Ruo-Nan’s daughter might live, but we could be forgoing our own futures to make that happen.

Both films show maternal figures that discover too late that they have unknowingly become imbricated into an undead heritage that will cost them their children and, by implication, any kind of future. In Hereditary, ignoring of the signs of the past is almost wilful in Annie’s pursuit of an understanding of a world that she feels she is central to, when in fact she constantly contrives to remove herself from it and, consequently, any meaningful possibility of intervention. This can be read, in a pre-Covid world, as a humanity too involved in itself to understand the true meaning of its past or of its place within it, and that understanding will only occur when it is too late to do anything about it. Ruo-nan from Incantation, was similarly too self-absorbed to realize what she and her friends were getting themselves into or the nature of the undead heritage they were inviting into their lives. However, the curse here is far more virulent in nature and, once invited into the environment beyond the village, spreads its curse without restraint — as also seen in films like The Ring franchise (1995–2022), and the Ju On franchise (2000–20), which also often feature maternal protagonists. Equally, then, Ruo-nan, like Annie before her, has lost her children/child and a possible future through not understanding the past or the nature of the undead heritage she has become part of. What is slightly different in Incantation and, I would argue makes it more of a “pandemic” film, is her willingness to “spread” the curse to others in an attempt to save her child. There is no sense of acceptance that one has transgressed the past and a price must be paid, rather it moves the focus on alleviating one’s own problems regardless of the costs to others.

Ruo-nan’s selfish act seems to resonate with much in the present predicament of humanity, which seems to wilfully ignore the clues from the past that tell of modes of damage and exploitation that have blighted our environment and our intercultural relations, continuing to deny any responsibility and, consequently, inviting the curse of an undead heritage that will inevitably consume us. Of particular note is the growing sense that we are no longer in this together and that individual actors are increasingly focused on saving themselves or their own. Annie’s self-absorption might have exacerbated her predicament and allowed for an undead heritage to be visited upon the world, but Ruo-nan, even though she won’t be there herself, is willing to risk the world for her daughter’s future. A seemingly noble endeavour, but one that purposely endangers humanity itself.

Simon Bacon, author of The Undead in the 21st Century: A Companion and series editor, Genre Fiction and Film Companions

[1] There is much here that confirms to fantasy author Terry Pratchett’s idea that gods of any kind require human belief to remain alive, though in horror texts this has been extended to supplication, dreams and fear amongst other human emotions.

[2]Films like the Paranormal Activity franchise (2007–21) work on similar themes. I would like to thank the members of the SCMS Scholarly Horror Group on FB for their help and thoughts regarding the possible implications of the ending of Hereditary.

Toxic environments would seem to be a given in horror films, and the creation and representation of spaces from which terror and violence can suddenly emerge are an inherent part of the genre. However, the nature and texture — or, what we might call, context and characteristics — of that environment are necessarily linked to the specific cultural moment from which they emerge. One of our current greatest anxieties — spawned most recently by images of the fleeing refugees from Ukraine — is immigration or, more particularly, the experience of being an outsider. This brief blog post looks at three recent horror, or horror-adjacent, films that can be seen to explore this very particular 21st-century anxiety, though one that is arguably as old as the creation of human societies.

The idea of “home” and the tensions between “not home” and “unhome” are central to the texture of the toxic environments under discussion here. The immigrant experience as seen in horror films is one that often focuses on the intersection between “home” and “toxic”, where what is considered as home becomes toxic in some way — domestic violence, extreme poverty, or war — and so then becomes “not-home,” forcing them to leave and try to find a new home, or as is often the case a new “not-home”, but one that is less toxic — physically or psychologically dangerous — than their original home. Horror film, which is often the perfect medium for effectively representing the anxiety around the sudden changing of safe environments into extremely threatening ones, is well suited for narratives describing the alienation or out-of-placeness that immigrants feel in a new country. This in itself is a characteristic of more recent films on the topic and, unlike popular or populist discourse, does not solely focus on the dangers of outsiders but rather the danger faced by those deemed as outsiders.

In the case of the three films discussed here, the outsiders/immigrants depicted are themselves very contextual, in that the nationality of the immigrants carries a very weighted meaning in their host country (a very similar weightedness is seen more recently when contrasting Syrian immigrants arriving in Europe with those from Ukraine, for instance). In this sense, the immigrants depicted in each film are those that are less welcome than others and are arriving into an environment that is already made toxic by pre-existing nationalist cultural narratives that do not recognise them as individuals in need of help but instead as a xenophobic threat. Horror films take a particular approach to representing these tensions and anxieties, as opposed to more realist or documentary style narratives, as they are inherently expected to manifest psychological monstrosity in physical form, and this is clearly seen in the examples chosen below.

The three films chosen — Mum & Dad (Sheil: 2008), His House (Weekes: 2020), and No One Gets Out Alive (Minghini: 2021) — feature immigrants from Poland, Africa and Mexico, respectively, entering the UK and/or the US at times when a very particular stigma surrounded such moves. Each film takes great pains to speak to the cultural context and the specific texture of the toxic environment the protagonists find themselves in and how they might survive it.

Mum & Dad focuses on Lena (Olga Fedori), who has just arrived at Heathrow Airport in the hope of finding work and a better life than she had in Poland. The airport itself becomes symbolic of an environment she has no connection to, and she herself is depicted as a commodity (baggage) moving through it and prey to anyone that might claim her. A worker at the airport offers to help, finding a bond in their shared exploitation, but she turns out to be a decoy who takes the girl to her “parents”, who turn out be brutal captors who thrust her into a toxic world. The “traditional” British home shown is one so extreme as to be the equivalent of a house of horrors: the television continually plays porn, they brutalise and handicap their “children”, and they celebrate Christmas with a real crucified man with a tinsel crown. Here, the alienness of other cultures becomes the stuff of nightmares, creating a toxic environment that leaves Natalia changed forever, even though she manages to escape. With no recourse to the authorities, or money to return home, she is left the victim of a culture that violently insists on changing her and seeing her solely as a commodity to be used and disposed off once it no longer has any need for her.

His House sees Bol (Sopi Dirisu) and his wife Rial (Wunmi Mosaku) arrive in the UK from South Sudan, a nation in conflict and consequently wracked with poverty, drought and starvation. They enter into an immigration system that only begrudgingly helps them, moving them to a house in an area that does not welcome them. The toxicity of the system and environment around them seems to concentrate in their new “home,” which seems alive with malevolence against them. Here, though, the nature of Bol’s relationship to his former home, which seems to have decidedly become not-home, is seen to link directly to the toxicity of the environment where they now live. They had pretended someone else’s child was their own to escape and now the child is dead. The guilt of their actions in South Sudan and the ghost, or “apeth”, they brought with them resonates with the dilapidated nature of the house such that it seems the structure itself is marking it out as not-their-home, just like the government immigration system. This toxicity, though, is eventually diffused through a level of acceptance of their guilt for their actions in their former home — the resolution tying Bol and his wife more closely together — so that their current one, whilst not exactly becoming “homely”, is less not-home than it was before. Here as a family in a toxic environment they find a form of home within themselves, if not with the environment around them.

No One Gets Out Alive focuses on Ambar (Christina Rodlo), a Mexican immigrant illegally living in the US. Her mother has died and the poverty of her home drives her to find a new life in America. However, her relations that already live there want little to do with her, leaving her to struggle to find underpaid work and cheap lodgings to stay in — even one of her workmates swindles her out of what money she has. The toxicity of the city-scape she finds herself in translates poverty, hunger and job precarity into a gothic-laden lodging house run by middle-aged brothers that cater solely for immigrants. Ambar is quickly assailed by anxiety, apparitions and threats of physical violence. This escalates into actual violence as it transpires the brothers are feeding the untraceable and uncared for lodgers to an entity in the basement.

The denouement here, as with Mum & Dad, reveals the extreme violence of the immigrant experience in the face of the unknown traditions of a different culture yet, as with His House, for Ambar some of this is tempered by a reckoning with previous guilt related to her former “home” and an equally violent reaction against the alien culture to retain her own sense of self. Within this there is also a sense that she finds some points of connection to the alien culture via the entity in the basement, which is also an immigrant of sorts. Here then she establishes a different kind of “home”, where its toxicity becomes her own, or at least one that she understands more clearly now. As the film ends, Ambar has become reconciled with this new “not-home,” and not unlike Lena and Bol has been forced to readjust both her sense of self and what she considers “home” in light of her experiences.

The three films point to the inherent nature of a world moving ever more towards large-scale displacements for reasons of poverty, war or environmental disaster and where “not home” will become increasingly common for ever greater numbers of people. Horror might be able to show us how scary the sometimes toxic environment of “not-home” is for others and also highlight the importance of finding points of commonality between ours and others’ ideas of “home.”

Simon Bacon is the editor of the forthcoming collection Toxic Cultures: A Companion in the Genre Fiction and Film Companions series, for which he is also the series editor.

Note: Many thanks to the members of the SCMS Horror Studies Scholarly Interest Group on Facebook for their suggestions for similarly themed films and in helping to define the term “not-home”.

One might not naturally think of a disease as a transmedia narrative, let alone the centre of a multi-platform universe, yet by their very nature they move across media, from the individual to the social, from word of mouth to social media, from fact to fiction. Historically these transmedia outbreaks are made sense of after the fact, usually once data has been collected and interpreted. The Covid-19 pandemic is a little different in that not only is there constant access to a huge amount of information that is increasing daily, but it also has a narrative template through which this is being read.

This template, or ‘outbreak narrative’, is one that has been constructed between reality and fictional representation, in books and films, to create a narrative arc of contagion, one which has a start, a middle and an end, but also one which inherently creates a transmedia story-world around it that both explains and supports that arc. This short blog will lay out how this works in the current pandemic and how its narrative world is supported by earlier outbreaks, both real and fictional, yet is simultaneously working against its own successful completion, creating the possibility of a story that will never, truly end.

Priscilla Ward (2008) has described how, around the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the 1980s, certain narratives arose to explain the disease that were part science, part media reportage, part cultural imaginings. In many ways it describes a transmedia migration at its most fundamental, where bodily manifestations and oral accounts are recorded and interpreted, adapted for newspapers, news programmes and the popular imaginary, creating a kind of ongoing dialogue between actual events and cultural, fictional representations of them. Films, in particular, have played an important part in this process, presenting complex information in a form that is accessible (simplified) and culturally comprehensible — this equally skews or omits parts of the truth to fit existing cultural templates and preferences. This created a pandemic narrative that featured proscribed stages and tropes: 1) a disease originating in an undeveloped part of the world, often involving monkeys or bats, caused by human incursion into the animals’ natural habitat; 2) a ‘patient zero’, often combined with the idea of a ‘super spreader’; civilisation becomes aware of the outbreak, enforcing ‘contact tracing’ and ‘quarantine’; 3) a race against time to develop a vaccine; 4) and, finally, administering the vaccine and returning to ‘normality’.

A good example of how this narrative was used and affirmed in film and fed back to the popular imagination is Outbreak (Peterson: 1995), which follows much of the above template: a deadly virus from Africa (modelled on the HIV/AIDS epidemic); animals are involved; there is a ‘patient zero’, quarantine, contact tracing, a vaccine and a race to save humanity. Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion (2011) builds on and reinterprets the narrative world of Outbreak and has become the definitive film on the subject in the current pandemic. Originally released after SARS (2003) and Swine flu (2009–10), the film interprets what the world had just experienced, emphasising and adding new parts to the existing narrative.

The film begins with the outbreak already in progress with the designated ‘patient zero’, Beth Emhoff (Gwyneth Paltrow), flying back from Hong Kong, infecting people as she goes. Beth is shown as an unfaithful wife who meets an ex-lover on her journey, linking the narrative to that of the earlier AIDS epidemic, which was popularly associated with transgressive sex.

As the world (America) begins to realise that an outbreak is occurring, the investigative stage of the narrative begins, involving contact tracing and the search for the point of origin — a temporal and media movement that embodies what Jenkins calls ‘spreadability’ (2013), in some ways is a natural component of contagion. The outbreak narrative then crosses various media platforms (news media, tv, radio, social media and word of mouth) as well as crossing borders, becoming transmedial and transnational, as researchers follow its path back to where it started. Once contact tracing has begun and the severity of the outbreak has gained greater understanding, the fight for survival begins, which also has two parts: the first is quarantine and containment and the second is producing a cure (vaccine). The former then requires that the ‘readers’ or ‘players’ of the narrative comply with the instructions they are given, which also relies on the coherence and consistency of those directions. This further brings in a new set of players/authors in terms of government or large corporations to discover a cure and produce a vaccine. Interestingly, whilst part of the main outbreak narrative, vaccination development can become a separate but intricately connected one, as multiple governments and corporations become involved that try to gain their own authorial control and influence the overarching urtext of the outbreak narrative.

Of particular note at this stage is the production of counter narratives that often oppose the main one or redirect it for ends other than successfully finding a cure and saving lives as quickly as possible. Contagion touches on this in the figure of Alan Krumweide (Jude Law), a self-styled investigative journalist and blogger who begins to push a story that the outbreak might be being engineered by drug companies to make money and that the government might also be involved. The conspiracy theory finds traction online (stickability and spreadability) and Alan is invited onto news programmes, subsequently claiming to have contracted the disease and being cured by taking a homeopathic remedy (Forsythia), which miraculously saves his life (when he never had the disease, of course).

This aspect is an interesting addition to the outbreak narrative and one that had not occurred as explicitly in earlier films such as Outbreak. In many ways it acts as fan-fiction within the urtext and as a way of wresting authorial control, even if it has deadly real-world consequences. It also shows how different narrative worlds intersect and how narratives of espionage and conspiracy theory have been used to control the direction and possible readings of the original outbreak narrative. In the current pandemic, such battles for authorial control have created a plethora of contradictory narratives propagated by a wide range of authors, with many of them being purposely politicised and altering the shape of the resultant story-world. Unlike Contagion, Covid-19 has highlighted how much each aspect of the wider narrative can be altered to fit a political end beyond the goal of saving lives by weaponising actions such as hand washing, mask wearing, etc. Consequently, this creates narrative confusion and uneven implementation of measures across national and cultural boundaries due to the political leanings of the governments in charge.

As Contagion brings its narrative to close, we discover the outbreaks point of origin; an infection from a bat that eventually reaches Beth. The sense of narrative completion provided then allows ‘normality’ to return, whatever that may look like.

With Covid, though, it is already obvious that any real uncovering of where the outbreak began, and consequently how it might end, are buried in purposeful obfuscation. Did the virus begin in bats, or in pangolins? Where did it originate exactly and how did it spread? Indeed the outbreak narrative described in Outbreak and Contagion is predicated on the idea of a togetherness against the contagion, and the notion of the ‘fight to save humanity’ constructs this as a battle between victim (humanity) and foe (the disease). However, in many ways, this is the one aspect that continues to evade the current pandemic, with many players/readers refusing to acknowledge their place within a shared narrative. Without such central cohesion, the multiplicity of authors struggling for attention and control become increasingly destructive, using the natural stickiness of aspects of the narrative to pull it apart rather than guide it towards a coherent end point.

In this sense the existing outbreak narrative might itself be forced to mutate into one that has no beginning or end, but just keeps repeating as it continually moves across media from fact to fiction and back again. Here then actual reality or science will have little true bearing on the final outcome, as the only recognised ending will happen when enough users/players — whether national governments or large groups of like-minded citizens — co-opt authorial control to write their own version of how normality returns, regardless of its relation to the real-world or the pre-existing outbreak narrative.

Simon Bacon, Editor of Transmedia Cultures: A Companion

Works Cited

Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford and Joshua Green, Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture, New York: NYU Press, 2013.

Stolworthy, Jacob, “Contagion becomes one of most-watched films online in wake of coronavirus pandemic,” The Independent, 15 March 2020. < https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/news/contagion-coronavirus-download-watch-online-otorrent-warner-bros-cast-twitter-a9403256.html> Accessed 4 March 2021.

Ward, Priscilla, Contagious: Cultures, Carriers, and the Outbreak Narrative, Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

In light of recent world events, thinking about monsters almost inevitably leads one to ideas of disease and contagion. The monsters swirling around the Covid-19 are many, depending on your ideological view of the pandemic and where you are in the world — with geographical location being perhaps slightly less important than your economic one. The manifestation of the monstrosity of the virus can take the form of governmental inaction and/or ignorance, the face of those not wearing a mask or social distancing, or even the neo-liberalist supply and demand system itself. Indeed, it would seem in a pandemic there are too many monsters, too many faces that stare back at us and reflect our anxieties, or seem to embody the very danger of the virus.

We are still too close to the current outbreak for there to have been many artistic cultural expressions created in direct regard to it, but that does not mean that there are not earlier films that manage to touch on and express many of the societal and individual concerns that have arisen from it. Films such as Outbreak (Petersen: 1995) and Contagion (Soderbergh: 2011) would seem obvious choices, and unsurprisingly the latter film has seen a huge spike in popularity in recent months.

But these films often contain extraneous narrative points to create dramatic thrust that can obfuscate the realities of real-world pandemics. Contagion, in particular, promotes an over-importance on the elusive “patient zero” by attributing judgement and retribution on a philandering wife and mother, Beth Emhoff, and blame on a self-styled false prophet, Adam Krumwiede (Jude Law), who denies the virus, as opposed to the system that promotes and facilitates what he does. Similarly, there have been two subsequent films called Patient Zero — one by Bryan T. Jaynes (2012) and one by Stefan Ruzowitzky (2018) — and Cabin Fever 3: Patient Zero (Andrews: 2014), alongside various television series of the same name, that focus on this issue.

In fact, human anxieties connected to contagion, such as the unseen dangers from strangers and even those we love, have long been part of the Horror genre, in general, and the construction of its monsters, in particular. It is worth considering a wider range of examples that pick up on some central concerns around the Covid-19 outbreak and seeing what kinds of “faces” they propose for the monster of contagion. These features are not necessarily part of the virus’ “own story” as such, as with many monsters it does not get to speak for itself; rather, it is the narrative placed upon it by the communities trying to control, explain, and eradicate it.

At least for Western culture, the virus is seen as an invader from the East and in a curious way subliminally linked with the idea of the War on Terror, envisioning a kind of ideological weapon released on world. This equally explains much of the language around “war”, “battle”, “siege”, etc. that surrounds the reporting of the virus’ spread. Connected to this is the idea of “patient zero”, but here it is not just about the point of origin in the East, but in each country or community where the disease is found. The infected person becomes a monster that is perhaps unknowingly a carrier of the virus, keeping his or her presence a secret until others have been infected. Alongside this is the contagion’s invisibility, which means it is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, creating a constant anxiety around where and how one might get infected: from another person, touching a surface, or inhaling a stranger’s breath. This anxiety can only be relieved by covering one’s face or protecting oneself from the outside world, which then leads on to isolation and confinement.

The last important trope is disinformation, or the dissemination of willfully wrong and contrary information. One might almost assign this to the immune system of the virus itself in that it infects the “body” of the community by convincing it that the virus, or the danger it presents, does not exist.

There is certainly much here that resonates with vampire narratives: a contagion from the East, and which arrives in secret; the infected do not look different yet are carriers of the contagion and infect others; misinformation and hysteria accompany the burgeoning contagion spread by “agents” of the disease. Vampires like Renfield (Dwight Frye) in Dracula (Browning: 1931) and Knock (Alexander Granach) in Nosferatu (Murnau: 1922) seem to embody the virus as we know it. Nosferatu, in particular, shows death arriving with the vampire, spreading uncontrolled through the town, a silent almost invisible presence, just like the vampire’s shadow that can travel and enter in wherever it likes. In contrast, Dracula can only enter where he is invited in, and wearing special accoutrements can keep him at bay.

Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954) even more obviously plays on the idea of contagion, where a mysterious dust cloud blows around the globe, infecting everyone with an unknown disease. Some, with the help of medication, are able to survive, if not totally destroy the contagion, and move into an uncertain future. Matheson’s novel has been linked to the rise of the zombie apocalypse as envisioned by George Romero first scene in Night of the Living Dead (1968). In its many subsequent permutations, it often mirrors the spread of a virus, moving across populations, borders and continents. Whilst the zombie apocalypse represents a rather extreme scenario given the fortunately lower than expected mortality rate of Covid-19, the sense of anxiety and fear aroused in communities where the outbreak is heading towards is very real. World War Z, both novel (Brooks 2006) and film (Forster: 2013), capture the panic of the approaching and unstoppable contagion that either gently seeps into a population or breaks like a tremendous wave across its borders — interestingly, Brooks’ novel sees the outbreak originating in China due to the incursion of man into nature.

Something similar is seen in The Girl With All the Gifts where humanity becomes infected with a fungus. The fungus is shown as a variant of one that ordinarily only occurs in the South America rainforest and “zombifies” ants to spread its spores, but equally suggests that mankind has incurred into territory that should be left alone. As with Matheson’s novel, the effects upon the human population are catastrophic but similarly suggest that there is the hope of a new kind of society once the original contagion has receded.

The Strain (2014–17) by Guillermo del Toro and Chuck Hogan more directly focuses on the nature of the world that the current pandemic has so expertly taken advantage of. The original trilogy of novels (2009–11) by the same authors, from which the television series is taken, made much of the Master Vampire’s exploitation of consumerism and white corporate America in its bid to infect the world. However, by the time the series began in 2014, the rise of populism was already being felt and, by its conclusion, it can be seen to be directly criticizing the ideology behind Donald Trump’s administration.

The contagion here arrives in America by plane, a major contributor to the spread of the recent pandemic, and sees the asymptotic infected being released back into the wider community of New York where the contagion then runs riot. The Master Vampire in control of this outbreak has taken advantage of corporate America — largely through the figure of Eldritch Palmer, who literally embodies white privilege and wealth — and its integration into every part of human life, so that his contagion has an open invitation into the heart of the city and the nation. They have control over the communications networks and media outlets, allowing them to misdirect the people with “fake” news as the disease spreads further and wider across the community. Once the contagion has taken hold, the uninfected become cowed in their anxiety and fear of those infected (the vampires), meaning that they prefer staying isolated in the safety of their own homes.

Curiously the series ends with the world returning quickly to normal after the source of the contagion is destroyed — in the novels, the world is forever changed by it — however, the infection lays dormant, waiting to be re-energized at some unknown point in the future.

As such, The Strain captures much of the details around the edges of contagion and the ideological background that facilitates the disease’s entry and unchecked spread through society. What it fails to capture fully is the facelessness and ambiguity of the monster at the heart of the current Covid-19 outbreak: it probably was not manufactured, it possibly started in bats, it most likely came from a wet-market in Wuhan. Although the Master Vampire is actually more of a “soul” that travels between hosts, it is the various hosts’ faces, in their vampiric similarity — hairless, bloodless, ghostly white with pointed ears — that solidify it and give it form.

A film that escapes such explicitness and captures something more visceral about the Covid-19 pandemic is the film of Bird Box (Bier: 2019) based on the 2014 novel by Josh Malerman. As with many of the examples mentioned above, the unknown contagion spreads from the East — early reports suggesting Siberia in Russia — so that we see the main protagonist in the film, Malorie (Sandra Bullock), is with her sister Jessica (Sarah Paulson), watching reports on television about a mysterious disease in Europe in the morning and, by the afternoon, the pandemic has hit the city where they live and it has descended into panic and confusion.

People quite literally lose who they are and begin acting hysterically, lost within themselves and literally dead to the outside world. The only refuge is total isolation indoors and reducing any contact with the outside world to an absolute minimum. Indeed, the anxiety created around leaving the house, or letting anyone or anything in, reflects the kinds of extreme emotional states that typify many individual experiences around the recent coronavirus outbreak. Malorie shares the house with a few others and each of them describes a different face to the contagion with no two stories sounding the same, other than they risked their very lives in being “seen” by the unseeable virus.

However, others seem to revel in the dangers presented by the pandemic, trying to encourage others to embrace its deadly ramifications. One such person enters the house: Gary (Tom Hollander) has no signs of contagion (asymptomatic) until he begins drawing images of what he has “seen”, and every picture shows a different monsters, suggesting the pandemic does not just have a thousand faces but an entirely different manifestation for each of them. It is not so much invisible but so infinite to be beyond our comprehension.

The presence of the contaminated stranger destroys the isolated safety of the home, forcing Malorie to leave with Tom (Trevante Rhodes) and two babies that she refuses to name other than “Girl” and “Boy”. Five years pass and Tom is killed, forcing Malorie and the children to move on and take to the river. However, to ensure the safety of herself and the children, they all have to wear protection over their faces to stop the contagion entering their bodies. As they travel there are constant shouts and distractions encouraging her to remove her face covering, but she resists. After many hours on the river and a long trek through woodlands she finally reaches sanctuary. Once there she uncovers her face and names the children — Olympia and Tom — knowing this new place is safe from the contagion, envisioning it as a future that this disease will never be able to touch and she will never need to see any of the faces of the monster again.

In a sense, then, many of the contagion narratives here are not so much about how humanity deals with the outbreak, but what changes it leaves in its wake. As seen with recent events in relation to Covid-19, many envision a radically different future, or a “new now,” as seen in Bird Box, Girl With All the Gifts, or the novel of World War Z, where it ushers in a redistribution wealth and influence around the world. In these the “work” of the contagion is complete, its power spent signaling a time when whoever is left can rebuild an environment beyond the ideologies that unleashed and/or invited the disease to begin with. More troubling are narratives such as the film of World War Z, and the television series The Strain, as here the world returns to what it was almost immediately. No lessons have been learned and no change in behaviour or lifestyle is required: the same environment that created the outbreak is recreated, regardless of the inevitability of the outcome. The future becomes one of waiting for the undead monsters of contagion to raise again.

Simon Bacon, editor of Monsters: A Companion

This article looks at three recent, highly successful horror films A Quiet Place (Krasinski: 2018), Bird Box (Bier: 2018) and The Silence (Leonetti: 2019), all of which centre their respective plots around the horror of life in the twenty-first century and its intersection with ideas around deafness and/or blindness. It should be noted that whilst all the narratives contain characters that are shown as being either blind or deaf, it is actually the actions of not seeing, not hearing and not making-a-sound that are of prime importance to the various films’ outcomes.

Broadly speaking, all three movies fit into the category of Smart Horror, where narrative takes precedence over, though does not preclude, jump scares or graphic gore. The three films fit alongside other recent movies such as Hush (Flanagan: 2016) and Don’t Breathe (Alvarez: 2016), which feature blind and deaf central characters and represent these ways of being as equally a curse (a “disability”) and a blessing (a “gift”). Indeed, as with many other films showing blindness or deafness, they can be seen to fit into the rather simplistic and demeaning normative adage that both will inevitably cause heightened acuity in the other senses to “make up” for the deficiency. This, however, does not recognize difference and equality but replaces it with the category of “special” and/or “gifted”, which labels the deaf or blind person as being “safe” but still separate from normative society.[1] What is particular about A Quiet Place, Bird Box and The Silence is that they do not show individually motivated threats or household invasion, such as in Hush or Don’t Breathe, but an all-consuming plague and existential threat to humanity itself and it is only through being or mimicking deafness or blindness that a few might survive this barrage of excess.

The horror manifested by the plague is usually of mysterious origin, being from outer-space or a pre-historic cavern, and seems to be everywhere at once, but it is worth looking more closely at each film to see how blindness or deafness works within each and what it might say about the source and meaning of horror in each story.

Bird Box is set in the present day and shows a world succumbing to a mysterious invasion that is completely based on or around seeing. It began with unexplained mass suicides in Siberia — which resonates with The Thing (Carpenter: 1982) and an unearthed contagion that produces mass hysteria — and quickly spread across the globe. It is never specified exactly what the cause is other than that it’s possibly from beyond our world and that even a glimpse of these alien entities will cause the viewer to go insane — here there is a reference to Event Horizon (Anderson: 1997) and a Hell dimension where sensory excess causes people to gouge their own eyes out. The only way to survive this visual plague is to constantly wear a blindfold, effectively making oneself blind. The story follows Majorie (Sandra Bullock) who leaves the city to try to find a safe haven for herself and two children she has with her. This she eventually does when she comes across a school for the blind that is far away from built-up areas and has created something of a sanctuary for the “unsighted” away from the world, though in the book from which the film is taken the sanctuary is peopled by those who have gouged their eyes out. The screen adaptations of John Wyndham’s The Day of the Triffids (1951) also use the idea of a sanctuary in a world of the blind, though in the first film adaption of the same name by Peter Sekely in 1963, the sanctuary is overrun and abused by the sighted and, in the more recent mini-series by Nick Copus, is shown as corrupt from within. What is interesting in the film is that the unseen, but all-seeing, plague is more strongly associated with populated areas — Marjorie leaves the city to find safety — and is a kind of sensory overload, as though the victims are receiving too much sensation or information through their eyes for their brains to cope with, hence driving them insane.

A Quiet Place shows an indeterminate post-apocalyptic future where civilization has already collapsed and the cities have been abandoned. All this has happened due to the sudden invasion of a huge amount of deadly, flying creatures from another world — it is never revealed where the creatures might be from — who have amazingly sensitive hearing with which to pinpoint their victims. The film follows the Abbott family, whose eldest daughter, Regan (Millicent Simmonds), is deaf and which somehow makes them uniquely prepared for the situation they are in.[2] In fact, not only does the ability to use sign language keep them alive, but the cochlear implant that the father makes for his daughter turns out to be a weapon against the creatures. Although the set-up is slightly different from Bird Box, there is also the idea of sensory overload here as the creatures themselves can be seen to materialize or coalesce from the sensory excess of the twenty-first century and hence the need to abandon cities, as the focus of such excess, and retreat to places of extreme quiet. Even the dramatic effects that sonic feedback have on the monsters, discovered by accident, can be seen to be a kind of anti-sensory device, where the excess that created them also nullifies them.

Something similar occurs in The Silence, which is again set in the present, and where the Andrews family have a daughter, Ally (Kiernan Shipka), who has been deaf for the previous three years, when everything suddenly changes. Some researchers break into an underground cavern and release swarms of voracious, flesh-eating prehistoric flying reptiles, called Vesps, that have super sensitive hearing. The Vesps are attracted to noise and immediately head to the nearest cities to feed, prompting the Andrews to leave for quieter surroundings in the countryside.

As in A Quiet Place, the ability to communicate without speaking is central to the family surviving and, after a run-in with a cult that wants the girl for themselves, the use of silent communication allows the Andrews to reach a refuge and plan for a future where, maybe, everyone learns to live quietly. The film combines the two earlier ones, seeing the creatures released by twenty-first-century technology but not so easily dispelled, requiring sanctuary away from the sensory excess of the modern world to plan some kind of possible future.

In this way, it is possible to read all these creatures as a manifestation of our lifestyles in the twenty-first century and the kinds of sensory overload that can be provided via visual, aural and even smart technology. All the films show humanity being literally consumed by this over-stimulation that will drive them either mad or tear them apart. Horror here, then, is invisible, a psychologically affective environment born of cognitive dissonance, which is the uncontrollable and uncontainable essence of life in the twenty-first century: not the extremes of politics, religion, greed, or even climate, but the “noise” created by, in, and around them.

In this sense the films go against the premise of other such recent Smart Horror narratives such as The Ritual (Bruckner: 2017), Get Out (Peele: 2017) and The Apostle (Evans: 2018), where leaving the city is the most dangerous thing you can do, and usually because there is a loss of communication and/or signal which separates the protagonists from civilization and the present.[3] In Bird Box, A Quiet Place and The Silence these are the very things that bring about death and destruction: the modern world will literally kill you. Within this then, anything that separates individuals from social normativity is a vital means of survival; perceived disability, social exclusion and otherness then become the markers of those that can survive the horrors of twenty-first century, an evolutionary adaptation that can negate the sensorial and cognitive overload or a world that is just too much.

Simon Bacon, editor of Horror: A Companion

[1] See Terri Thrower, ‘Overcoming the Need to “Overcome”: Challenging Disability Narratives in “The Miracle”,’ in Marja Evelyn Mogk, ed., Different Bodies: Essays on Disability in Film and Television (Jefferson: McFarland & Co.: 2013), pp 205–18. (Go Back)

[2] Though it should be mentioned they lose their youngest son to the creatures. (Go Back)

[3] Interestingly, It Follows (Mitchell: 2014) occurs on the suburban area between the city and the countryside where urban decay is seeing the rural slowly reclaiming the land, or the city slowly regressing back to it. (Go Back)

June Boyce-Tillman, editor of the book series Music and Spirituality

This is the sixth and final part in a series on Finding Forgiveness.

My searching has taken me into many different areas — sometimes rewarded with success, sometimes less so — most of them involving, ritual, prayer creativity and music.

Around the years of my searching, the landscape of our culture has changed in a huge variety of ways; this quest has enabled me to find my place within these various changes. The danger of the present situation is that people become defined by their childhood experiences which are often seen as a pathology. For a long time, I lived with the idea that there was a June who had not been abused and was not wounded. The notion that I could be healed and attain that imagined personhood was quite comforting — that these early experiences could be taken away. This was, of course, a lie. There is no alternative me — only the one with the life story set out here.

The real question is how we use the legacy of our younger lives. Some talk of leaving them behind, others of forgetting them and others of forgiving. The last term has been popular with the Church, which, as we have seen, has been concerned more about the product — the final destination — rather than the complex route of getting there. It has ignored, in particular, the place of anger in the complex process. Indeed, the stages of forgiveness are not unlike those set out by Elisabeth Kubler Ross for the grieving process: denial, anger, bargaining, depression/sadness, acceptance/celebration. These stages may overlap and may last a lifetime. However, it is important to enable people to move beyond the stages of victimhood and surviving, towards celebration.

It has been suggested to me by well-meaning helpers that forgiving is also for the benefit of the perpetrator and that a carefully monitored face-to-face meeting between the survivor and perpetrator is mutually advantageous. But in this narrative the perpetrator is dead. But the concept that forgiveness is a gift bestowed to aid the perpetrator is to misunderstand the power of forgiveness for the survivor; forgiveness (often fueled by understanding) enables the survivor of injustice to let it go or rather, as I prefer to regard it, to use it as a mulch that is recycled in a life:

The idea of unfinished projects and unused experiences as mulch derives from Alan Bennett:

Creativity is a real player in the game of recycling. I called my book on healing The Wounds that sing. The story of highly creative people shows how they plumb the depths of their lives to produce their creations. But these people are regularly pathologised, because they often experience life so intensely and have considerable mood swings. Support is also necessary. I have had good professional support for some time: establishing a group of friends who can cope with me in my darkest moods has been an effective way of managing the most difficult parts of myself.

Belonging has always been a problem for me. The isolation of childhood abuse is very wounding. It was only in the middle of my life, that I found places where I really felt I belonged. The history of the Church, in relation to people who are different, is not good. There often appears to be more concern about who to keep out, rather than who to welcome in. There are exceptions, one of which I found at St James’ Piccadilly, but my experience of the Church has often been bruising. Yet I hang on in there; it is still my spiritual home. In the end, to rediscover gratitude is a real antidote to depression. Gratitude can be expressed for little things as well as big. Each night I write down five things for which I am grateful that day.

It is via gratitude that we approach wonder or amazement. There is a sense in which wonder restores the innocence that may have been taken from us quite early. This is how God comforts Job, in that enigmatic book in the Hebrew Scriptures. God shows Job the variety and the wildness of nature, reveals Job’s place in a greater cosmic scheme, a place that can be reached in this life, not only via dying.[4] Dying was my way out for so many years and now the rediscovery of the liminal space in this life — embracing it and finding ways to access it — has been an important part of my journeying into the Divine loving.

It took a great deal of prayer and support to do carry out this ritual of forgiveness. I had been worrying for many years about how to resolve my story. It did not involve courts and lawyers but a private acknowledgement. It involved a grasp of ritual as a way of dealing with the past.

It was a very long journey and involved so many different stages and emotions. It demanded a great deal of perseverance and in the end I tried to encapsulate in a very long song to the tune of My bonny lies over the ocean.

Forgiveness Journey

[1] Boyce-Tillman, June (2006). A Rainbow to Heaven — Hymns, Songs and Chants. London: Stainer and Bell, p. 98. @Stainer and Bell.

[2] Bennett, Alan (2016). Keeping on keeping on. London: Faber and Faber, p. 103.

[3] June Boyce-Tillman, started in Norway 2008

[4] Brown, William B. (2014). Wisdom’s wonder: Character, Creation and Crisis in the Bible’s Wisdom’s literature. Grand Rapids, MI and Cambridge UK: William Eerdmans Publishing.

[5] Written by June Boyce-Tillman March 29th 2018 (Maundy Thursday) finished on Easter Sunday Aril 1st.

June Boyce-Tillman, editor of the book series Music and Spirituality

This is part 5 in a series on Finding Forgiveness.

It was Palm Sunday in Florence and the processions of waving olive branches filled my heart. I was sitting in the portico of a palace, when the mobile phone rang and told me that my abuser had died.

Was it really all over? I remembered the festivals when the family gathered together — the darkened room and sitting on his knee and his desire for me to make him happy. It was when I arrived in England that the tears started. Now I had my final chance to put it behind me, if only I could face that coffin. I knew about coffins. After all, I had worked briefly for an undertaker, which had taught me about that. I knew the feel of the dead — I knew how to

- Love them

- Talk to them

- Give them their final blessing

- Sense their presence or absence

Saturday dawned well. The taxi would come at 8.15 for a train that would get me there at 11.15. The train rumbled through the beautiful countryside. When I got to the coffin, he looked old — not like I remembered him at all. He was fatter then and there were no glasses. I tried to imagine this old man young — the thick lips, the fatter cheeks. His hands were red with bruising — had they put drips in when he died? They looked oddly, in this Holy Week season, like crucified hands. Had I crucified him? Was that how he had seen it? These were the hands that had touched me, that had given me, so early, the delights of sex. And now, they were red and raw. I could not touch them yet. I had to look at them and get used to them. Would they rise up and touch me again?

I started to talk to him. Did he remember our time together — the darkness — how he would make me into a proper woman (did he not realise I was actually a child?) And then I moved to the gifts, the gifts born of the experiences that he had given: the large pieces I had written, the struggle to be a composer and finally a priest. I talked of the hymns I had written and I sang him my hymn on love:

Could I set him free? I, who held onto things so long, whose house was filled with a collection of sentimental junk from which I could not be separated? What would it mean to let him go?

What was the good he sought? And I knew. He had wanted to be a priest but what he had done to me had stopped him.

I had certainly stood alone throughout my life. Plagued by loneliness, depression, with very little family to speak of and alienated by this experience from the ones I might have had, I had been on a long journey, carried by my faith and the religious rituals that I and my friends had devised:

And now we both were moving on — he to his eternal rest and me onto I knew not what. But I knew that my faith would lead me, as it had for so long, and that it would not rest until I found my eternal home, but that it might be more restful with him gone if only I could let him go.

This was the real prayer. And then it happened. To the side of the statue of Jesus, he appeared as a young man in his brown sports jacket, which I had forgotten; I knew he was waiting to go. He had come out from the old dead man: the young soul, waiting to go into the arms of his Lord or to be reborn, however you saw it. I went to my carefully packed bag and found the oils, put on the stole and opened the small bottle of oil. as a memorial,” I thought. I went over and touched his forehead. It was cold and firm. I made the cross again on his forehead and started on the ancient prayer:

The young man in the sports jacket was surrounded by angels. And then I knew he was gone. I sat on the chair, away from the body and imagined the magnificent Elgar setting of the text of Praise to the Holiest in the Height. I heard it in all its majesty with unusual joy.

[1] Boyce-Tillman, June (2006). A Rainbow to Heaven — Hymns, Songs and Chants. London: Stainer and Bell. @Stainer and Bell p. 83

[2] Boyce-Tillman, June (2006). A Rainbow to Heaven — Hymns, Songs and Chants. London: Stainer and Bell. @Stainer and Bell

June Boyce-Tillman, editor of the book series Music and Spirituality

This is part 4 in a series on Finding Forgiveness.

The Church often preaches an instant forgiveness with little informed help:

Christians have too often met [survivors of abuse] instead with indifference, suspicion and incredulity. They have been reluctant to address their cry for care and their cry for justice. They have preferred to advise, preach and give their counsel rather than to listen, learn and simply be alongside. They have thought that they know the journey to be travelled and the speed it should take, and have sometimes compounded suffering and harm through what was imagined to be pastoral ministry. [1]

Others indicate that forgiveness is not at all possible and leave people in the permanent state of survivor. This book sets out the lengthiness of the journey but the possibility of an arrival:

VIA NEGATIVE

Bilinda[2] (2014) (who lost her husband in Rwanda) presents us with four choices at the outset:

- To acknowledge the reality of what had happened

- To reject revenge

- To acknowledge the common humanity of all involved

- To believe that God’s love could enable repentance on the part of the perpetrator.

Put together from other writers, there are many stages in what is a long and complex process:

- First stage — a safe place for the expression of anger and fear

- The need for the offence to be accepted as real and not forgotten[3]

- ‘Forgive and forget’ owes more to King Lear than Christian theology [4]

- The second stage — naming the shame and guilt

- The third stage — reconciliation with the self and giving up self-persecution by damaging behaviours

- Giving up the survivor identity — can be done through creativity, ritual and a supportive community[5]

Forgiveness is a process not a product and can be lifelong for the deepest wounds. Not to forgive is to damage not the other person, but one’s self. It is to let go of the past and not be continually trapped by it. I have learned this slowly and painstakingly. I have had good tools:

- Faith — meaning-making

- Prayer — re-centering

- Ritual

- Creativity

- Support by people with a similar meaning frame as yourself

- Belonging

- Gratitude

- Wonder

- Embracing paradox

Questions: Where does forgiveness come from? Where are you in that process, personally and culturally? Does your church teach forgiveness or simply preach it?

[1] The Faith and Order Commission (2016). The Gospel, Sexual Abuse and the Church; A theological resource for the local church. London: Church House Publishing, p. 40.

[2] Bilinda, Lesley (2014). Remembering Well: The Role of forgiveness in Remembrance. Anvil, 30 (2), contacted 1 February 2018.

[3] Flaherty, S. M. (1992). Woman, why do you weep? Spirituality for survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.p141

[4] Fortune, Marie (2002). Pastoral responses to sexual assault and abuse: Laying a foundation. Journal of Religion and abuse, 3 (3), pp. 9–112.

[4] Shooter, Susan (2016). How survivors of abuse relate to God. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 12–14.

June Boyce-Tillman, editor of the book series Music and Spirituality

This is part 3 in a series on Finding Forgiveness.

In part 2, I shared some personal examples of which have enabled the process of establishing an authentic interiority following traumatic experiences in myself.

Since then a number of people have come to me with a similar history to mine. They somehow know mine, I think, at some level. Some come for advice and some to tell me old stories. As a result, I wrote this hymn reflecting on it all to the tune Finlandia — usually used for the hymn: Be still my soul.

What I have set out in this book how I have recycled and turned the legacy of the past into a rich compost that can grow into celebration and creativity. This has been partly though music (the freedom song of the title): hymns, longer works and the one-woman performances. These have played a significant part in the healing process for myself and others. Recently, in South Africa, after a performance of my show Seeing in the Dark (which is on the subject of abuse) an unknown man came up to me in tears, talking of his own healing and thanking me for telling his story.

I am hoping that my story may help people managing the complexity of their own life-story, to mulch it down into authentic interiorities. God has been good to me. I still find a Christian frame one that enables me to make meaning effectively. Within this frame, life is a journey into understanding Divine love in all its varied forms. In an age where love is often portrayed as an erotic relationship between two people, my life has revealed both the cost and the blessings of loving. People enculturated in other faiths may well make meaning differently. The important thing is to have a sense of a wider picture, into which your story fits. The Christian frame that I have used offered me s hope — perhaps the most significant of all virtues. I have had a long joyful journey but the destination has been worth it.

RE-MEMBERING

[1] Berry, Jan, and Pratt, Andrew (2017). Hymns of Hope and Healing: Words and Music to refresh the Church’s ministry of healing. London: Stainer and Bell. p92. @Stainer and Bell

[2] June Boyce-Tillman to the tune Adapted from the Handel aria: Lascia ch’io pianga. Berry, Jan, and Pratt, Andrew (2017). Hymns of Hope and Healing: Words and Music to refresh the Church’s ministry of healing. London: Stainer and Bell. p123 @ Stainer and Bell

de

de  fr

fr