A (S)Mothering Inheritance in an Age of Precarity, or, We’re Too Removed from the World to Ever Be in It

This blog post will look at two films, Hereditary (2018) by Ari Aster and Incantation (2022) by Kevin Ko. On the surface they seem very different from each other, with Aster’s film being labelled as “elevated” horror, with a very thoughtful and aestheticized approach to set design, camera work and pacing, while Ko’s relies heavily on a found-footage aesthetic, frenetic action and continual jump scares. In many senses, they serve as examples of the opposing poles of recent horror, one concentrating on a more intellectual and artistic approach (Hereditary) and the other being very referential to the wider genre and often dependent on many sudden shocks and scares (Incantation).

However, while both share elements often attributed to the Folk Horror subgenre — plots involving non-majority religious cults and rural settings — this article will argue they share a far deeper connection through what we might call an “undead heritage” that is focused around a maternal figure. This can seen to be linked to the more well-known ideas of a family curse or “the sins of the fathers/mothers”, although strong male figures are largely absent in both films. This theme has very specific connotations in the twenty-first century that are strongly indicative of the “age of precarity” we are currently experiencing in the 2020s and our inability to protect our futures.

“Undead”, here, as more fully explored in The Undead in the 21st Century: A Companion, signifies an entity that is neither dead nor alive — even beyond life and death, in some way — and driven by an insatiable desire to consume, or find sustenance in, humanity. In both these films, this “undeadness” is manifested in a god-like, supernatural entity that is outside human conceptions of life and death — effectively immortal in most senses of the word — and which is compelled to draw the life from humanity,[1] and, more specifically, humans linked by family bonds, using a ritual of some kind (this often requires the recitation of a text that “invites” the undead entity “in” and consequently “curses” the recitee). Curses or undead language is of note in each film as the person being cursed does not need to know what they’re saying, but the performative nature of the recitation acts as an invitation to the undead entity.

This idea of unknowing is important for the undead heritage theme, as it often belies an inability of the present — as embodied in the victim — to understand the meaning of the past that is often in plain sight. The victims inevitably only understand the meaning of the “clues” of the past when it is too late and they are about to be consumed by their undead heritage (a common theme in Folk Horror). Indeed, unknowingness plays a large part in many forms of precarity, particularly in relation to contemporary ecological and political environments.

Before looking at the films more closely, it should be mentioned that the two narratives look at undead heritage slightly differently and, cultural specificity aside, also point to a slightly different view of the world in 2022 than in pre-pandemic 2018.

Hereditary features Annie (Toni Collette), who is grieving the recent death of her mother. Their relationship in life was extremely problematic, even abusive, and although Annie is surrounded by both physical and psychological memories of her mother’s past, she prefers to reconstruct the present to try to understand her increasing sense of foreboding. On top of this, her daughter, Charlie (Milly Shapiro) is decapitated in a freak accident involving Peter (Alex Wolff), her son and Charlie’s brother. Annie meets Joan (Ann Dowd) at a bereavement group and she admits to her she had “given” Charlie to her mother as a placatory measure, but it had left her even more excluded from both of their lives. Indeed, Annie appears deeply removed both from the feminine heritage of her own family (her mother and her daughter) and the world around her, and the lifelike models she makes are attempts to control and place herself in her environment.

Joan gets increasingly close to her and reveals that she has managed to contact the dead and can show Annie how to do it, too. Annie then performs the ritual as described to her by Joan, importantly reciting a verse of a language she doesn’t understand, and forcing her husband and son to do so with her. This effectively invites the demon king Paimon into the human world, allowing him to possess the body of her son and kill all those that are not supplicants to his power. It seems that Annie’s mother was a high priestess who had linked Paimon to the “soul” of Charlie, who should have been born a boy, and now wants to inhabit Peter. It is only at this point, once her undead heritage has overtaken her, that Annie realizes what is occurring and that the clues were all around her in her mother’s belongings: Joan is in her mother’s photos of occult rituals, and highlighted passages in her copies of esoteric books all point toward worship of Paimon and inviting him into the world through the body of a boy.[2]

It also gives further meaning to the distance from her own children and her subconscious attempts to kill them — in not killing them, she has effectively ended the world as we know it. Overwhelmed by her undead heritage and her inability to protect her family or herself, Annie loses her grip on reality, her identity and literally, her head, as Paimon possesses the body of Peter and becomes manifest. Exactly what Paimon intends is not made clear, though one suspects it will add to the precarity of a world already out of balance, though one that neither Annie or her family will be part of.

Incantation focuses on Ruo-nan (Hsuan-yen Tsai), whose life is a frantic pastiche of flashbacks and ragged camera footage as she tries to hold on to the present and envision a future for her young daughter. The curse she now carries is not her own but one that she stumbled upon, bringing the undead heritage of others into her own familial lineage. Some time ago, Ruo-nan and a group of “Ghostbuster” friends went to the ancestral village in rural Taiwan of one of their number. The villagers and the friend’s relations told them to leave as a special and potentially dangerous ritual was being performed, but the rebellious friends stayed, interrupting the ceremony and breaking into the shrine, despite all the warnings they were repeatedly given.

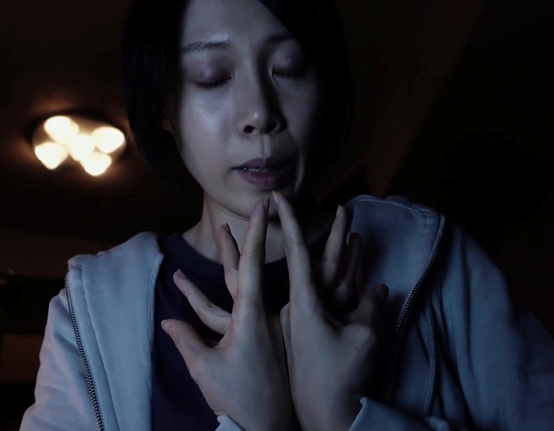

Not all the friends escape, as some unseen power overtakes them and Ruo-nan, who unbeknownst to herself was pregnant, was forced to recite a “blessing” while placing her hands in a special configuration. Deeply affected by the events, Ruo-nan gives up her child and only many years later feels strong enough to reclaim her from those caring for her. It is only at this point that her undead heritage begins to catch up with her and she soon realizes that it’s been passed on to her daughter. Now that the curse is starting to affect her life, she decides to investigate further to understand what she and her friends had done and pieces together what the past actually means for her daughter’s future.

The curse seems to take the form of ever-increasing precarity as Ruo-Nan’s actions become progressively frantic and her life spins out of her control.

It transpires that the village worshiped a malevolent deity and that the “blessing” — which takes the form of a multi-syllabic phrase — is in fact a curse, that when repeated invites it into your life and slowly kills you. Ruo-nan’s daughter, Dodo (Sin-ting Huang), even after following the advice of local religious healers, is getting increasingly worse, so she goes back to the village, the past, to undo the present. However, once there, she goes into the depths of the underground shrine to confront the image of the deity and realizes that once the curse, the undead heritage, has been invited in, it cannot be revoked but only lessened through sharing.

Ruo-nan then ends the film as it started, as she has done at various points throughout the narrative, inviting us the audience to recite the inverted blessing so that we might share the curse and lessen its affects on her daughter. Here, then, Ruo-nan’s gradual understanding of the undead heritage she has released mirrors our own, as we realize that the phrase we have been asked to recite has cursed us: Ruo-Nan’s daughter might live, but we could be forgoing our own futures to make that happen.

Both films show maternal figures that discover too late that they have unknowingly become imbricated into an undead heritage that will cost them their children and, by implication, any kind of future. In Hereditary, ignoring of the signs of the past is almost wilful in Annie’s pursuit of an understanding of a world that she feels she is central to, when in fact she constantly contrives to remove herself from it and, consequently, any meaningful possibility of intervention. This can be read, in a pre-Covid world, as a humanity too involved in itself to understand the true meaning of its past or of its place within it, and that understanding will only occur when it is too late to do anything about it. Ruo-nan from Incantation, was similarly too self-absorbed to realize what she and her friends were getting themselves into or the nature of the undead heritage they were inviting into their lives. However, the curse here is far more virulent in nature and, once invited into the environment beyond the village, spreads its curse without restraint — as also seen in films like The Ring franchise (1995–2022), and the Ju On franchise (2000–20), which also often feature maternal protagonists. Equally, then, Ruo-nan, like Annie before her, has lost her children/child and a possible future through not understanding the past or the nature of the undead heritage she has become part of. What is slightly different in Incantation and, I would argue makes it more of a “pandemic” film, is her willingness to “spread” the curse to others in an attempt to save her child. There is no sense of acceptance that one has transgressed the past and a price must be paid, rather it moves the focus on alleviating one’s own problems regardless of the costs to others.

Ruo-nan’s selfish act seems to resonate with much in the present predicament of humanity, which seems to wilfully ignore the clues from the past that tell of modes of damage and exploitation that have blighted our environment and our intercultural relations, continuing to deny any responsibility and, consequently, inviting the curse of an undead heritage that will inevitably consume us. Of particular note is the growing sense that we are no longer in this together and that individual actors are increasingly focused on saving themselves or their own. Annie’s self-absorption might have exacerbated her predicament and allowed for an undead heritage to be visited upon the world, but Ruo-nan, even though she won’t be there herself, is willing to risk the world for her daughter’s future. A seemingly noble endeavour, but one that purposely endangers humanity itself.

Simon Bacon, author of The Undead in the 21st Century: A Companion and series editor, Genre Fiction and Film Companions

[1] There is much here that confirms to fantasy author Terry Pratchett’s idea that gods of any kind require human belief to remain alive, though in horror texts this has been extended to supplication, dreams and fear amongst other human emotions.

[2]Films like the Paranormal Activity franchise (2007–21) work on similar themes. I would like to thank the members of the SCMS Scholarly Horror Group on FB for their help and thoughts regarding the possible implications of the ending of Hereditary.

de

de  fr

fr